CAROVA BEACH – When Wash Woods Coast Guard Station was built a century ago on an isolated beach on the Currituck Outer Banks, it was not extraordinary. It was No. 166 on the list of the Coast Guard stations constructed along the Atlantic coast, and its architecture was characteristically utilitarian and sturdy.

What is extraordinary is that it is still right there, surrounded by sand, overlooking the ocean. If it wasn’t for Doug and Sharon Twiddy, Wash Woods Coast Guard Station would have been long gone.

Supporter Spotlight

“Thank you for making an investment in the future by making an investment in the past,” U.S. Rep. Walter Jones, R-N.C., told the couple during a 100th anniversary ceremony held Oct. 20 at the station.

Jones’ family and the Twiddy family became close friends in Edenton, where Jones grew up.

“This goes way back,” he said later. “I feel like I’m at a family reunion.”

Jones said that he believes that much strength comes from people knowing the history of their nation, using the example of the Kennedy assassination documents that were recently released as an example.

“You cannot move forward unless you protect the history,” he said. ‘The Twiddy family has made a commitment that years from now, people can see what it used to be.”

Supporter Spotlight

In brief remarks, Doug Twiddy, 71, thanked the attendees gathered under a tent set up on the beach between the station’s quarters and the boathouse. Many of them had helped in the station’s rehabilitation, and others had direct history with the community.

Clark Twiddy, his son, lauded his parents’ dedication to preservation. In addition to Wash Woods, the Twiddys relocated and restored the Kill Devil Hills Lifesaving Station, which now serves as the Twiddy vacation rental company’s office in Corolla. They also restored the Corolla schoolhouse, numerous structures in historic Corolla Village and a 1930s beach cottage.

“This station was paid for by private money,” he said. “Doug did all the heavy lifting on this restoration – he worked tirelessly.”

Eleven years after Twiddy & Co. opened its first real estate office in Duck, the Twiddys purchased the long-vacant Wash Woods station in 1989 from a private owner, likely saving it from demolition. Located in the North Swan Beach community – part of the off-road area generically known as Carova – the property is 7 miles up the beach from the paved road in Corolla.

By then, the station had already toughed out decades of storms and neglect. The federal government had purchased the station’s land from the Swan Island Club, an old waterfowl hunt club and recorded the deed on June 16, 1917, according to information provided by Twiddys. The Wash Wood station, named after an old community to the north, was in operation by 1919. It was one of about 30 Chatham-type stations, two-story rectilinear structures designed to provide more living and work space for crews.

After the original station house was lifted and stabilized by pilings, the Twiddys, using old photographs for reference, stripped the interior down to its original plaster walls and heart-pine floor and painted it with its original colors. Although an upstairs wall was removed and a second bathroom was added, the house retains the architectural character and simple charm of the Coast Guard design. Today, the building serves as the company’s Carova office.

In 2007, the couple built a boathouse based on a design similar to the original. It is located closer to the ocean and is used by the Twiddys as a private retreat. A few years later, a replica of the station’s original copper-roofed lookout tower was built by historic preservation craftsman Christian Thompson. In 2011, he moved the completed structure in parts from his Kill Devil Hills driveway to the site. And in 2012, the original cookhouse behind the station house was renovated and now boasts a full-service kitchen.

Although the station looks very similar to the original Wash Woods, in perfect, almost movie-set fashion, the beach neighborhood surrounding it has changed drastically. While historic Carova communities were hardly populated, contemporary Carova has many expensive large “cottages” lining the oceanfront, as well as a growing year-round community. Enormous numbers of summer vacationers crowd the beaches and backroads with off-road vehicles, anxious to spy the wild horses that roam freely.

But come fall, the crowds are gone, and the wide-open beach is as inviting as ever.

“It’s been a long time since I’ve been this far, I’ll tell you,” Jones said, noting the considerable trek to the station, situated just minutes from the Virginia border. “I last came here seven or eight years ago. I wish I had been able to be here 30 times.”

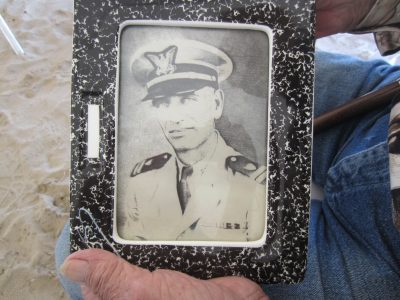

Ernie Bowden, 93, is one of the few who straddles the old days and the modern days, and he stayed in the thick of it almost the whole time. Stopping by after the ceremony, Bowden said he was born in his grandmother’s house in the nearby Seagull community, where she was a registered midwife. His father, Bill, who served 24 years in the Coast Guard, was then stationed at False Cape, just over the Virginia border, and later at Kill Devil Hills and New York. For about three months in 1937, he was stationed at Wash Woods in the North Swan Beach community.

Bowden, a former cattle rancher and a member of the Currituck County Board of Commissioners on-and-off from 1976 to 2008, said that two of his uncles also had been stationed at Wash Woods at different times.

It’s remarkable that the Wash Woods was standing at all when the Twiddys bought it, considering it was not elevated like oceanfront buildings are today. Bowden said the beach was flat, and there were no large dunes to buffer the house from the surf.

He remembers hearing an uncle’s description of the powerful 1933 hurricane striking Wash Woods. “The ocean came in the front door,” he recounted, “and went out the back.”

Bowden, who was 8 years old then, remembers his father floating a dory to the front door of their False Cape home and taking the family to spend the afternoon and night at a hunt club that was three-quarters of a mile from the ocean.

In those days, it was a small, tight community, Bowden said, adding he was never bored. Boys made slingshots from tree branches and old tires and competed in marksmanship contests. They rode horses. Daily chores included gathering firewood every day, much of it driftwood, and carrying buckets of pumped water to the house.

Many people left the beach right before World War II. Bowden eventually left for a while for work. When he returned, he lived with his father at the decommissioned Wash Woods Coast Guard Station for 20 years. He later moved to his own land and managed as many as 300 head of cattle and ran a hunt club.

Carova, which didn’t have electricity until 1968 or public telephone service until 1974, started changing after the state of Virginia in 1974 bought the land that became False Cape State Park and fenced the North Carolina border. And that’s about when Bowden started getting interested in politics, and he didn’t quit until he lost the election in 2008.

Jones said that it’s stories like Bowden’s, and the Coast Guard’s, that are so important to the Outer Banks.

And it’s not just about the protection the Coast Guard has provided for mariners along the coast, and from enemies who threatened the U.S., it’s also about the communities like Wash Woods.

“There’s so much history in this area,” Jones said. “Our children need to learn. They need an opportunity to come here and see this.”