KURE BEACH – Anyone who has ambled around the Fort Fisher historic site has seen firsthand a slice of North Carolina’s past.

Supporter Spotlight

The mounds of the Civil War earthworks fort are still evident more than 150 years later. Other aspects of that wartime history remain, too, but are less obvious. Those who’ve walked along the site’s seaside revetment have likely passed within 800 yards of a sunken blockade runner. That shipwreck is now the state’s first Heritage Dive Site with more in the works.

The vessel, the Condor, ran aground on Oct. 1, 1864, and it’s perhaps best known as the event that led to the death of one of its passengers, Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow. But there’s a lot more to know about the wreckage and North Carolina officials are hoping residents and tourists will want to dive below the surface to learn more. Two white mooring buoys now mark the site so divers and snorkelers can see what remains of the blockade runner, which rests just 25 feet under water.

“It’s so close to the surface,” said Gordon Watts of the Institute of International Maritime Research. “It’s really the only time machine we have, and you can go back in time.”

“We have such a rich history off our coast,” said Susi Hamilton of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, who along with Watts, appeared at a dedication ceremony for the site earlier this month.

The Heritage Dive Site program is meant to increase appreciation for the treacherous waters off the state’s coast often called the Graveyard of the Atlantic. There are close to 5,000 documented wrecks off the North Carolina shore.

Supporter Spotlight

“We’ve only found 996 of them,” said Greg Stratton, archaeological dive supervisor with the state’s Underwater Archaeology Branch. Stratton was among those who placed the lines and buoys so others can find the dive site. “We want people to see what we see when we dive.”

A sense of excitement and enthusiasm for the site can lead to increased tourism and preservation, officials said.

“What we’ve found is that, long term, there’s increased stewardship at these sites,” Hamilton said.

North Carolina’s program is based on one in Florida, which now boasts 12 such dive sites. John W. “Billy Ray” Morris III, deputy state archaeologist with the branch, started tentative plans for the Condor site in the 1990s, but the real push to get it ready has only taken place in the past year. One of the primary reasons this wreckage is the state’s first Heritage Dive Site is that it is still mostly intact. Another is its history.

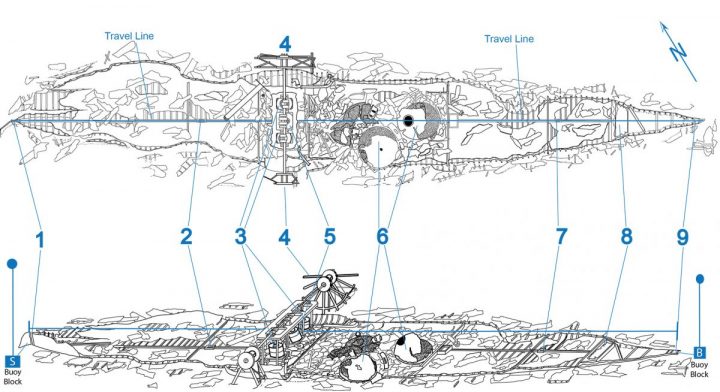

Originally 220 feet long, the Condor was one of five Falcon-Class steamers built in Glasgow, Scotland, for the purpose evading Union blockades of Southern ports and waterways. These were typically lightweight, shallow-draft vessels capable of outrunning and outmaneuvering patrol ships and transporting cargo that included guns and other ordnance. Larger cargo ships would travel from Europe to Bermuda, for example, and a smaller amount of supplies would be loaded onto these quicker vessels that had a better chance of making past Union forces and to their destinations, Stratton said. Today, 218.6 feet remain of the Condor.

“And it’s in fantastic condition,” Morris said.

Divers, using a dive slate prepared for the project, can see parts of the starboard and port paddle wheels and iron-and-copper steam machinery.

On its maiden voyage, the Condor traveled a well-documented path. It first sailed from Scotland to Ireland and was carrying uniforms for Confederate forces. At this point, both Greenhow and Lt. Joseph D. “Fighting Joe” Wilson, a surviving officer from the raider CSS Alabama, were on board. It then arrived in Bermuda on Sept. 1, 1864, and, instead of sailing to North Carolina, it traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to pick up coal, supplies and J.P. Holcombe, a Confederate agent who had been organizing transportation for escaped Confederate prisoners. A Newfoundland puppy was also on board, belonging to pilot Thomas Brinkman.

As it sailed to the New Inlet, the Condor veered to avoid the Nighthawk, another Confederate blockade runner that, unknown to the Condor crew, had run aground two days prior. Greenhow wanted to be rowed ashore because she feared capture. As she was wearing heavy clothing, and carrying a large amount of gold meant for the Confederacy, she drowned when rough waters capsized the boat. She was later given a full military funeral and buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington. Others, including the puppy, safely made it to shore.

More Dive Sites Planned

The Condor wreckage was chosen as the state’s first dive site because it is so close to the beach.

“We can actually keep an eye on it from the office,” Stratton said.

Divers can refer to numbered placards at the site. Snorkelers can also enjoy the site, especially if the weather is clear. Non-diving visitors can also take a sort of Condor tour, by checking out a replica at the Fort Fisher State Historic Site visitor center and then stopping by the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher to see photos and engine replicas.

Several groups worked together to make the Heritage Dive site happen, in addition to the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Hamilton said. These include North Carolina Sea Grant, Friends of Fort Fisher, Fort Fisher State Historic Site and local dive shops.

There are more in the works. The hope is that in about a year, another Heritage Dive Site will open, Stratton said.

“We have a five-year plan to have three or four by that time, including one in the Outer Banks,” he said. “This is a part of our shared heritage. And we want to help people enjoy it and teach them how to take care of it. Eventually, it will deteriorate, as all things do in the ocean. But it’s here now.”

Both Stratton and Watts said the wreck of the U.S.S. Peterhoff, also off Kure Beach, could be one of the next sites. The Peterhoff was a British vessel that had been seized by the Union Navy in February 1863 and put into service to blockade Wilmington. The Peterhoff was sunk during its first week of blockading duty after being rammed by the gunboat Monticello, whose crew mistook it as a blockade runner.

“Peterhoff was a large iron vessel and there is an extensive amount of surviving hull structure and steam machinery,” Watts said. “Several of the large cannons that were thrown overboard are still visible on the bottom near the hull.”

“The spectrum of shipwrecks off the North Carolina coast and in the sounds and rivers spans the entire history of the state,” Watts said. “They preserve an exciting physical record that can significantly enhance our knowledge of the past and our collective maritime heritage.”