ROANOKE ISLAND — The American Thanksgiving tradition may have begun when English settlers on coastal Massachusetts had dinner with Algonquian natives they knew in the 1620s. But here on coastal North Carolina, English visitors and native Americans feasted together a generation before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth.

Whether the Pilgrims continued their friendly dinner meetings with the natives does not matter. We still celebrate and remember Thanksgiving in November as a time when two very different cultures of people were thankful to be eating together.

Supporter Spotlight

We know that good times did not last long here between the settlers who spoke English and the people who spoke the Algonquian language. Of the 17,000 North Carolina coastal plain aborigines believed to have lived here when white men first joined them in the late 1500s, only about 5 percent remained 200 years later. A great many died of new diseases. Others just moved on, by choice or by force. Still others became part of the society we know today.

Sailing for the French crown in the spring of 1524, the Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano and his crew found the Algonquians on our coast “very courteous and welcome.” After cruising up the coast from Cape Fear where they had encountered a local young man, the sailors went ashore to the Kitty Hawk area, which the captain named Arcadia, “owing to the beauty of its trees.” There they introduced themselves to a women accompanied by a younger woman about 18 years old and several children. Trying to share food with these locals, the men met mixed results. In Verrazzano’s report to King Francis I, he said, “When we met them, they began to shout. The old woman made signs to us that the men had fled to the woods. We gave her some of our food to eat, which she accepted with great pleasure; the young woman refused everything and threw it angrily to the ground. We took the boy from the old woman to carry back to France, and we wanted to take the young woman, who was very beautiful and tall, but it was impossible to take her to the sea because of the loud cries she uttered. And as we were a long way from the ship and had to pass through several woods, we decided to leave her behind, and took only the boy.”

In 1525, a Portuguese captain Estavo Gomez took a group of natives from these parts to Spain, but the Spanish reportedly protested the act, and Gomez set the captives free in Spain.

Stray white men no doubt landed on the Outer Banks during the ensuing years. Some may have acclimated themselves to the Algonquian way of living. At the time, Algonquian communities spread throughout what is today northeastern North Carolina. The tribes were the southernmost of those descended from Algonquian-speaking people of northeastern America, whose ancestors had migrated across Canada during some 12,000 years previously. Some say the tribes were pushed down this way because they were weak, peaceful agrarians, but maybe they simply liked the climate and the promise of the place, like present-day migrants.

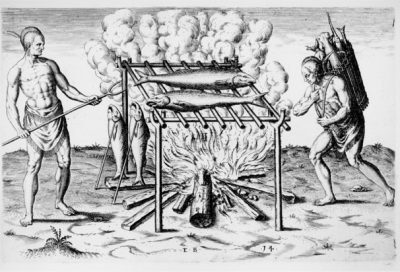

By the year 1000, Algonquians were well established in the northeastern North Carolina coastal plain. Over the next 600 years, they developed a civil and healthy society of more than 7,000 persons in many villages located between southeastern Virginia and Cape Lookout. They lived in bentwood-framed houses covered with bark and woven grass mats, and they frequented seasonal fishing and hunting camps. They danced to spirits in temples and around bonfires. They ate abundant food from the woods, water and gardens, smoked tobacco and drank yaupon tea, and fought with other tribes from time to time.

Supporter Spotlight

Sixteenth Century Neighborhoods

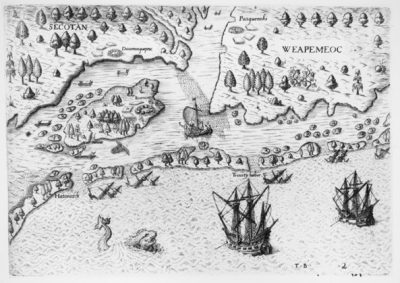

The political map of the North Carolina coastal plain by the late 1500s resembled today’s Middle East, where tribal factions bore thin allegiance to one another. Some did not share the same language, customs or religious outlook. Most of the coastal residents spoke the Algonquian language. Iroquoian-speaking people lived farther inland, west of the Chowan River, and they extended to the Cape Fear area. Some Siouan-speaking tribes also occupied territory in eastern North Carolina.

The Chowan (an Algonquian term translated as “people at the South”) lived along the Chowan River and were the most powerful Algonquian of the region, with a population estimated at 3,000 in the year 1600. The Weapemeoc were related to the Chowan and the Powhatan in Virginia, and they lived in today’s Perquimans, Pasquotank, Camden and Currituck counties. The Secotan (“burned place”) occupied the coastal territory from below Albemarle Sound west to today’s Beaufort County and south into most of Hyde County. The Machapunga (“bad dust” or “much dirt”) were Secotan relatives who lived in the mainland Hyde County area, and they had a village called Mattamuskeet. Secotan also included the tribe of Roanoke (generally translated as “rubbed” or “polished” wampum or money) and inhabitants of the Croatoan area. “Croatoan” appears in some 17th century maps as located on today’s Dare County mainland, but earlier English referred to the residents of the Outer Banks as Croatoan as well. Manteo was a chief among them, and Wanchese equally noble. The group of barrier island people who lived, probably seasonally, in today’s Buxton woods territory, later were known as the Hatteras (“there is less vegetation”).

When the first of Sir Walter Raleigh’s expeditions, led by Master Arthur Barlowe and Capt. Philip Amadas, arrived on Roanoke Island in the summer of 1584, the local people offered the newcomers deerskin in trade for swords so they could fight some nearby warriors. The Englishmen did not yield their swords, Barlowe reported in his journal, “The First Voyage to Roanoke, 1584.”

In the Secotan region of modern mainland Dare County, the rich man werowance or king of the Roanoke tribe was Wingina, who lived in the village of Dasamonquepeuc near today’s Manns Harbor. The mainland people canoed to Roanoke Island in good weather and had a seasonal village there. The king’s brother, Granganimeo, greeted Barlowe’s ship one day while it was at anchor in the sound, and he accepted gifts of food, a hat and a shirt. Granganimeo in turn gathered a canoe-load of fish and presented it to the English. Was this the first Thanksgiving between English tourists and native Outer Bankers?

Granganimeo continued to send food to the English that summer, including, said Barlowe, “a brace or two of fat bucks, conies [rabbits], hares, fish, the best of the world … divers kinds of fruits, melons, walnuts, cucumbers, gourds, peas, and divers roots and fruits very excellent good, and of their country corn, which is very white, fair, and well tasted.”

Extreme Southern Hospitality

A more festive occasion – perhaps even more festive than our contemporary version of Thanksgiving – occurred less than a month later in August 1584 when Barlowe and seven men had dinner at Granganimeo’s house. The English that day had sailed 20 miles up today’s Croatan Sound, Barlowe wrote later, and on their way back anchored at Granganimeo’s Roanoke village on the north end of the island. Granganimeo was out of town, but his wife, along with other “gentle, loving and faithful” women welcomed the Englishmen to visit in a comparatively spacious, five-room longhouse. “She caused us to sit down by a great fire,” Barlowe recalled, “and after took off our clothes and washed them, and dried them again; some of the women plucked off our stockings and washed them, some washed our feet in warm water, and she herself took great pains to see all things ordered in the best manner she could, making great haste to dress some meat for us to eat.” They feasted on boiled grain pudding, venison, roasted fish, melons, roots, fruits, wine and ginger water. Then they were “entertained with all love and kindness.” When some braves appeared with bows and arrows, the hostess “beat the poor fellows out of the gate.” She invited the sailors to stay the night, but Barlowe figured the eight men would be more comfortable aboard ship and declined the invitation. So their hostess packed them a supper and asked 30 Roanoke women and a few men to accompany the visitors to the ship. During the evening, Barlowe reported, the women on shore continued to invite the sailors to “rest in their houses.”

A year later, manners had broken down. Granganimeo welcomed the second Raleigh expedition, but good relations didn’t last. The newcomers could not grow comfortable with the local habits, and the Roanoke were just as mystified by the white men. As Roanoke people sickened and died of strange new diseases (smallpox, typhus), they noticed the white men weren’t as affected. They also were curious why these men had no women with them. Some Roanoke people surely wondered, “These white men must be immortal.”

Ralph Lane, a military man, was the new English governor in the Raleigh expedition of 1585. After a Roanoke local took a silver cup from the English camp, Lane ordered an assault on the suspect’s village and reported that the Englishmen “burned and spoiled their corn and town, all the people fled.” This group of English clearly had no appreciation of the local society and food.

Nevertheless, Granganimeo’s father, revered as the local community priest, convinced his other son, king Wingina, and the community to help the English survive the winter of 1585-1586. Wingina, meanwhile, plotted with neighboring tribes to rid the island of the whites.

Wingina saw his brother Granganimeo and father die that year, perhaps of disease. Ralph Lane expected trouble and sent a peace party to Wingina’s mainland village. There, the English shot and killed the king and his men.

It is no wonder that difficulty with their Indian neighbors beset the 112 English men and women who came to live on Roanoke Island the next year, 1587. The Algonquian communities survived; the sole English community did not. The English colony was “lost.”