HAVELOCK – A proposed state highway in Craven County continues to draw criticism from environmentalists who argue that the state’s preferred location for a U.S. 70 bypass would destroy habitat crucial to endangered birds and rare plants.

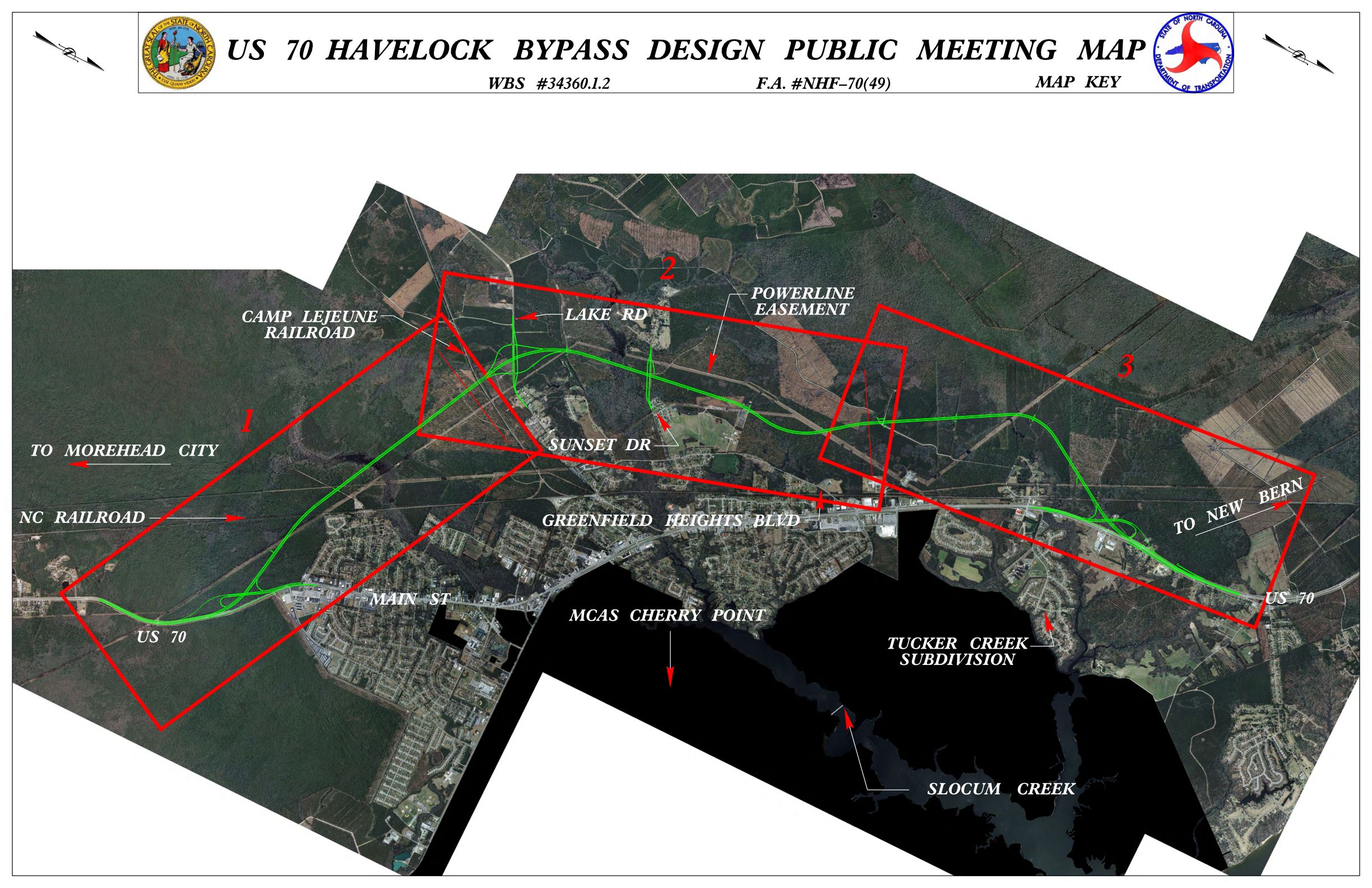

N.C. Department of Transportation officials are preparing an environmental document for a proposed divided, four-lane bypass that will cut through the Croatan National Forest on the west side of Havelock.

Supporter Spotlight

The so-called “record of decision” will identify the selected alternative and also discuss all of the alternatives considered during the planning and design process. It will also describe the measures DOT took to avoid and minimize environmental harm and programs for the implementation of mitigation measures. The document must also include the agency’s responses to public comments on the final environmental impact statement, or EIS, which DOT released last year.

DOT plans right to begin right-of-way acquisitions for the $173 million project as early as this year with a projected construction start date of 2018.

Transportation officials initially identified the need for a bypass around the city in the mid-1970s, but funding, environmental issues and other road projects pushed the Havelock bypass onto the back burner. Heavy traffic, particularly in the summer when beachgoers head to the ocean, clog Havelock’s main thoroughfare, which has more than a dozen stoplights.

Some environmentalists, including the Croatan group of the N.C. Sierra Club, say DOT’s environmental study for the project is inadequate and that it minimizes the ecological significance of the portion of forest that will be impacted.

The Sierra Club addressed several environmental concerns to DOT and the Forest Service in 2011. Club members in March raised those same concerns in a 21-page letter to the head of National Forests in North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

“They’ve just been so, so locked into their decisions all through this process,” said John Fussell, a consulting biologist and Sierra Club conservation committee member.

DOT initially selected its preferred location for a Havelock bypass in January 1998. Fussell said that much of the initial environmental study done nearly 20 years ago was incorporated in the EIS that was released in October.

According to the final study, the preferred location is cheaper than other alternatives because it’s a shorter distance and it would displace fewer homes. The preferred alternative, alternative 3, also offers the best compromise between effects on the city and the Croatan National Forest.

The trade-off, according to the study, is that though alternative 3 would affect the highest acreage of wetlands – 140 acres – and the greatest acreage of national forest – 240 acres – of all the alternatives, there will be fewer effects to habitat fragmentation and home relocations.

An estimated 16 residences, three small businesses and Craven County’s Waste Transfer Facility would have to be relocated to make way for the 10.1-mile-long bypass. The DOT bypass project development engineer did not respond to a request for comment.

Alternative 3 may have less of an effect on people, but the preferred location would have a significant effect on the federally protected red-cockaded woodpecker, Fussell said.

“Habitat for those woodpeckers is going to be taken out and fragmented,” he said.

The bypass will be built through red-cockaded woodpecker “clusters” where some of the longleaf pines in which they live are upwards of 95 years old.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers prefer mature, longleaf pine forests generally more than 80 years old. They are the only woodpeckers that excavate cavities solely in living pine trees.

The assemblage of cavity trees is called a cluster. The average cluster is about 10 acres and may include up to 20 or more cavity trees.

“The highway dissects the very best habitat for the woodpeckers in one section,” Fussell said.

To help the woodpeckers’ habitat, DOT and U.S. Forest Service officials have developed a prescribed burn plan. Longleaf pine ecosystems depend on fire because the trees need to be able to germinate and grow in open ground. Without periodic fires, fallen pine needles will blanket the ground and prevent seeds from sprouting. Those that do get shaded out by faster growing trees and shrubs.

Croatan District Ranger Jim Gumm said the plan is to burn between four to six hours every few years.

“What we’re looking at is probably a long morning into the early afternoon,” he said. “One day would be the expectation. It doesn’t have to happen every year. The normal burn rotation around here is about every three years.”

Forestry officials prefer to initially burn in the winter to clear out underbrush then again in the summer, which is the most effective season to burn, Gumm said.

DOT will have to close the bypass during burns. The Forest Service will coordinate burns during the week to reduce the effect on traffic.

This is just another challenge the Croatan faces as an urban forest, Gumm said. He said he understands Fussell’s concerns, but that the Forest Service’s own endangered species experts have said the bypass will not have a significant effect on woodpecker habitat.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that the biological assessment conducted by DOT and the Forest Service was sufficient and agreed that the burn plan will help sustain woodpecker habitat. The Fish and Wildlife Service decided a formal consultation was not needed.

Fish and Wildlife Service also agreed with the biological assessment’s conclusion that the bypass “may affect, not likely to adversely affect” the red-cockaded woodpecker and rough-leaved loosestrife, an endangered perennial herb.

But Fussell questions whether routine controlled burns will actually occur once the bypass is open.

“As far as the woodpeckers, the one thing they’re saying is there’s not going to be a problem if burning can still take place,” he said. “If the highway gets some special designation is it going to make it harder to burn? I think it’s very fair to be skeptical that burning will take place.”

The Forest Service is not able to conduct enough prescribed burns to restore habitat for certain rare, loamy soil savanna species, according to the Sierra Club letter.

DOT and the Forest Service have been collecting seeds from goldenrods, Le Conte’s thistles and awned mountain mint populations to replant in other areas of the Croatan, according to the EIS.

Le Conte’s thistle is not listed as endangered or threatened, but it may be one of the rarest, Fussell said.

“Right now the Croatan has the largest few remaining populations,” he said. “One site will totally be destroyed by the bypass. The other, some of it will be destroyed. My thought is this plant has been declining so do you really know that replanting is going to be successful?”

The highway would cut through one of the most unique power line corridor sites in the Croatan, he said. This corridor has loamy soils, which contain a balance of sand, silt and clay.

Regular mowing in the corridor, which has some of the nicest loamy soil in the Croatan, has maintained the longleaf savanna that several rare plant species rely upon, Fussell said.

The longleaf pine ecosystem in the United States has vastly diminished and altered since the early 1700s due to European settlement, commercial timber harvesting and tree farming, urbanization and agriculture.

The coastal plain of the southeastern United States once included an estimated 70 million acres of longleaf pine. Only about 1,500 acres of virgin, pre-settlement longleaf pine forest remains, according to the Longleaf Ecology and Forestry Society.

“The Croatan, even though it’s fairly small and fragmented, it’s one of the most significant areas of that ecosystem,” Fussell said. “The EIS definitely did not give a good idea of the area being impacted by the bypass. The amount of longleaf, the age of the longleaf, the relatively contiguous state of the longleaf, the two natural heritage areas – there is no appreciation of the longleaf in the study.”

The bypass would affect two significant natural heritage areas – the Southwest Prong Flatwoods Natural Heritage Area (NHA) and the Havelock Station NHA, according to the Sierra Club.

“The discussion in the FEIS about these two natural heritage areas is surprisingly brief and does little to provide an appreciation of the significance of the two areas, although it does point out that the Southwest Prong Flatwoods NHA contains one of the best examples in the state of a mesic pine savanna (Coastal Plain subtype),” according to their letter. “More importantly, the FEIS does not describe the degree to which the ecological significance of these two NHA’s would be impacted by the introduction of a highway.”

The letter goes on to say that not all rare plants and animal species in the project area have been identified or acknowledged in the state’s environmental study.

“We’re still finding species,” Fussell said. “Some of these power line corridors where I’ve gone every year for years, I’m still finding things.”