Steve Dinkelacker isn’t wild about the idea that the state’s main wildlife commission floated recently about allowing an alligator hunt in North Carolina. A certified wildlife biologist and an expert on alligators in North Carolina, Dinkelacker isn’t anti-hunting, or even against hunting alligators in North Carolina… someday.

“I can envision an alligator hunt in the state,” said Dinkelacker, who is a biology professor at Framingham State University in Massachusetts, but has conducted years of research on the animals here. “And I understand the appeal. It’s an apex predator, one of the ultimate prizes for any hunter. It’s like a bear.

Supporter Spotlight

“But I can’t support it in North Carolina yet,” he continued. “A lot more research is needed before anyone can be sure that any alligator hunt in North Carolina won’t harm the species. The data just isn’t there. ”

Supporter Spotlight

Dinkelacker recently expressed that same opinion in formal comments to the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, which has proposed an alligator hunt in the state in 2016 and will take public comments in a series of hearings, including one in Edenton on Tuesday at 7 p.m. and another the next day at the same time at Craven Community College in New Bern.

According to the commission’s public notice, the proposed season would be from Sept. 1 to Oct. 1, by permit only, with a bag limit of one alligator that can be taken with a catch pole, harpoon, gig, wooden peg, bang stick and bow and arrow. A gun could be used only to “dispatch” alligators that are restrained.

In the official public hearing document, the commission states that a hunt is justified because, “There is increased interest in hunting American alligators in eastern North Carolina, and population evaluations indicate that the population can sustain a limited harvest.”

How Many Out There?

Dinkelacker doesn’t doubt the interest – generated in large part by increased sightings of and confrontations, however benign, with alligators – but he and others have serious doubts about the population estimates and the methodology.

“You can see a lot of alligators in one place, but they will be totally absent in others,” he said. “And what they have primarily based their numbers on is what’s called a ‘spotlight survey.’” That amounts to cruising along waterways and using a powerful spotlight to seek the telltale red shine of gators’ eyes.

Chris Moorman, coordinator of fisheries, wildlife and conservation biology programs at N.C. State University in Raleigh, led the most recent significant study, in 2012-13, and his report did indeed find plenty of alligators, comparatively speaking.

The research team covered a similar compilation of lakes, rivers and swamps in 25 counties as a previous survey published in 1986 did, and coordinated it with commission biologists and officers. They counted 117 gators on 103 routes.

In June 2013, according to the report, the team focused more intensely on the most productive gator locations, and estimated 672 gators on 43 routes, using a statistical model to estimate animals that were likely there, but hidden from the spotlights.

But Moorman’s report concluded that a harvest might send overall numbers falling by removing females from the population, in large part because alligators in North Carolina – the northern limit of their range – don’t grow and reproduce nearly as fast here as they do in warmer states like Louisiana or Florida. Females here don’t reproduce until they are 18-20 years old, or perhaps older, compared to 10 years, for example, in Louisiana. Females ‘gators here also have fewer babies.

In his comments to the commission, Dinkelacker stated that, “To my knowledge, nothing is known about alligator reproduction in N.C… Best guess scenarios would probably use data from South Carolina, which are probably incorrect for North Carolina, given the latitudinal and habitat differences.”

Hunters typically take both males and females, since the sexes look alike, according to Dinkelacker. Alligators longer than 10 feet are usually males, but those less than 10 feet long can be either sex. Moorman said in an interview that his work couldn’t give an accurate estimate of the total gator population in the state, although that could be done through modeling if the commission wanted it done. And, he said, the geographical differences in the population are striking, or at least were he’s done his work.

Some Numbers

For example, the teams found 53 alligators in Lake Ellis Simon near Havelock, in the central coastal region, up from 33 in the last count in the early 1980s, and 79, up from 40, at Orton Pond in Brunswick County, but only a few in the most northern sampling site, Merchants Millpond State Park near Virginia.

As a result of the long time period necessary for reproduction and the geographic distribution, Moorman said, the report concluded that, “even low levels of female harvest would cause populations to transition from stable or slightly increasing to a state of decline.”

The report also said alligators were most abundant in areas where they are most protected, including military bases, national forests and private property with restricted access to water bodies. He pointed out that alligators in North Carolina are susceptible to harsh winters, and can be affected adversely by hurricanes, too. That relative abundance in protected areas, Dinkelacker said, points out the continued fragility of the population and the likely problems if hunting were to be allowed.

Moorman, like Dinkelacker, said he’s not necessarily against an eventual alligator hunt. “We were only concerned … about … what would maintain a stable population,” he said.

Dinkelacker said the surveys in North Carolina have not been adequate to justify a hunt. “It’s like counting deer,” he said. “You can go out in one area one night and count 10, then count two in the same area the next night, then 20 the next night. What’s the real number? You don’t know. All you can really say is, ‘Yes, there are deer.’ It’s much the same with alligators. And I’m just not confident that is adequate to justify a hunt, especially given the long, long time it takes a female to reach reproductive size in North Carolina. It’s not like Florida, where there clearly are a LOT of alligators, up to a million by some estimates. That gives you some margin of error. In North Carolina, there just isn’t enough data.”

Dinkelacker knows that North Carolina is the only state in the American alligator’s range where a hunt is not allowed, and he knows there’s a lot of pressure to allow one. But he also noted that alligators can be taken now, if they are a problem, under a “depredation” permit, by state agents.

If the state wants to allow a hunt, Dinkelacker said, it should invest the necessary resources to get a population estimate that supports the contention that a hunt is sustainable.

The American alligator was listed as “threatened” on the U.S. Endangered Species List in the 1960s. They had become became scarce early in the 20th century, because of loss of habitat, in part, and unregulated hunting.

“We don’t want the alligator to disappear, for a variety of reasons,” Dinkelacker said. “An apex predator affects a lot of things.”

For example, they eat nutria and beavers. Those animals, he said, can play roles, some known, some not known, in flood control.

‘Delicate Balance’

John Hammond, a fish and wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Raleigh, said that while it’s true that the American alligator was “de-listed” in the 1980s, the slow reproduction of alligators in the state make a hunt at least somewhat problematic; it’s difficult to know what level of hunting would render the population unsustainable.

His agency, he said, hasn’t taken a position on the hunting proposal and would work with the commission if the state decides to allow hunting.

“It’s a delicate balance, though,” Hammond cautioned. “If a hunt is allowed, it would certainly be wise to keep a close eye on what happens. We look at the ecosystem as a whole, and the alligator is an important part of it.”

Then, too, Dinkelacker said, there’s the simple fact that the alligator is a native species, and one that many want to see, alive. “It is a magnificent creature,” he said. “People might be afraid of them, but many do want to see them, and not just on a wall somewhere.”

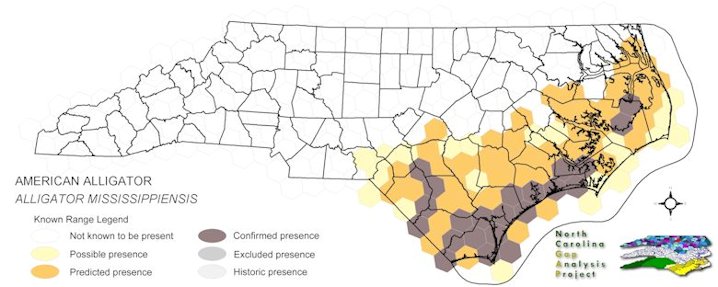

Dinkelacker, like Moorman, noted that no matter the accuracy of the surveys, it is very clear that alligator populations in North Carolina vary widely by region, with far more in the southeast and relatively few in the northeast. While there is some indication the gator is extending its range northward, both said, if that’s occurring, it’s a very slow move.

Still, Allen Boynton, the commission’s diversity coordinator, said the regional distribution could be a reason to establish different hunting rules in different areas, or for allowing a hunt in one area and not in another, should the commission approve a hunt. “We do that all the time,” he said. “A good example is deer. We have a shorter season in the mountains, and we don’t allow dogs in the hunt there.”

Boynton said he believes the numbers do make a case to justify a limited gator hunt, and agreed there’s a lot of interest.

Part of that interest, he said, is obviously that people are seeing more alligators – and they don’t want to see them in their swimming pools or too near them on the golf course – and part of it is the popularity of “gator hunt” shows, such as Louisiana-based “Swamp People,” on television. Hunters also hear friends from other states talk about alligator hunting.

Boynton, though also understands the scientists’ concerns. “They (alligators) do grow much more slowly here,” he said. “But if we do allow a hunt, and really all we’re doing right now is getting public input, we would take that into consideration, and we’d be very careful. We’d certainly increase our monitoring of the population so we’d know what would happen.”

Although there have been a lot of budget cuts in the state in recent years, Boynton believes the commission could find partners in the state universities to handle the additional monitoring and research.

He also noted that while the number of alligators in North Carolina is small in comparison to the numbers in other states, the American alligator population as a whole has been growing throughout the range. The main reason it’s still protected, he said, is because it’s so similar in appearance to the crocodile, which is considered more threatened.

Boynton noted that the commission’s discussion about a potential hunt took into account the need to maintain a stable alligator population because a big decline in numbers would diminish “viewing opportunities” that could affect some businesses.

The commission, he said, does not plan to charge for the permit itself, but could charge potential hunters a $5 fee to enter a lottery to win a permit.

It’s not hard to kill gators, Dinkelacker notes, and he worries about. “You can just throw out a baited hook,” he said. “It’s kind of like setting a crab pot. How hard is that? And you can shoot one in a ditch from the back of a truck. I’m not judging anyone. Again, I’m not against hunting, and I get why people want to hunt alligators. I just think the data we have isn’t good yet. I think it is premature.”