Proponents of offshore drilling predict that a massive new workforce could be on North Carolina’s horizon if oil and gas resources are tapped in the Atlantic Ocean.

The creation of new jobs – tens of thousands of them – would be one of the greatest economic gains to North Carolina from offshore drilling, proponents say.

Supporter Spotlight

Critics of drilling charge that the rosy job numbers are based on a flawed economic study commissioned by the oil industry. Reaching even those lofty numbers, they note, will requires hundreds of drilling rigs and a significant buildup of infrastructure that now doesn’t exist. Half of the revenue that the report predicts offshore drilling would contribute to the state’s budget relies on Congress changing federal law.

If proponents are right, this is a process that will take years and is highly dependent on the natural resources available, the success of striking oil and natural gas and where it will come ashore. It seems clear to everyone that the industry will be dependent on pulling trained workers from places like the Gulf of Mexico states through the foreseeable future.

Jobs, Jobs Jobs

The oil and gas industry’s labor force is a broad spectrum of higher educated petroleum engineers and geologists to “blue collar” drillers and mechanics, all well-paying positions essential to daily operations.

Those jobs create a complex myriad of onshore support services – helicopter companies that shuttle rig employees to and from shore, supply vessels, caterers, fabrication companies – the list goes on and on.

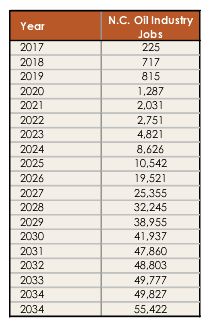

This translates into a projected 55,000 jobs in North Carolina by 2035, according to a report prepared for the American Petroleum Institute and National Ocean Industries Association.

Supporter Spotlight

The report forecasts North Carolina would benefit the most in oil and gas industry jobs of any state along the Eastern Seaboard with an estimated $4 billion increase in economic activity.

“It is four times the impact of revenue sharing on an annual basis,” said David McGowan, executive director of the N.C. Petroleum Council.

McGowan emphasized that the jobs created from offshore drilling will likely be more of an economic benefit to the state than federal royalty shares, which, unlike the jobs, are more of an uncertainty, he said.

The oil and gas industry workforce is aging and substantial turnover is anticipated in the next five to six years, adding to an already increasing demand for workers.

“We don’t have a tremendous knowledge base right now,” McGowan said of the state’s current natural oil and gas workforce. “As an industry we’ve been working with the community college system and university systems to see how we can get the programs in place in some of these schools. That’s all work that has to be done. I don’t know that it has to be done before the first activity starts.”

Don Briggs, president of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association, said the growth of industry jobs in North Carolina will depend on how successful drilling is off the coast.

“You have to put this into perspective,” he said. “Right now if they start some leasing off of North Carolina and drill some wells right in the beginning those would be mostly transit jobs in engineering and things like that. They’re going to have to use people from areas where the rigs are coming from and trained employees to work on those rigs. In the deep-water Gulf of Mexico when they start a project from the beginning to the end it’s around eight to 10 years. It takes a long time. It is a very complex procedure in drilling. It takes a lot of technology. It will be several years before you really know how good of a potential it could be.”

Growth Industry

The oil and gas industry grew by 71 percent between 2003 and 2011, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2011, the industry employed nearly half a million workers nationwide. Forty-eight percent of those consisted of jobs that supported oil and gas activities and 34 percent accounted for oil and gas extraction.

The bureau projects the oil and gas industry will employee 220,000 people by 2022. That number does not specifically factor into Atlantic drilling, said Andrew Hogan with bureau’s Employment Projections Office.

“It could be more than that, but we can’t say with certainty right now,” he said.

The API-funded Quest Offshore Resources report projects that by 2025 the industry will produce 78,098 jobs for offshore oil and natural gas exploration and production in the Atlantic outer continental shelf.

That number is forecasted to more than triple to more than 279,500 jobs by 2035, according to the Quest report.

To reach the numbers projected for North Carolina, about 15 oil and gas projects – a combination of permanent installations and mobile drilling rigs – would have to be operating off the coast by 2035, according to Sean Shafer, the report’s project director.

“A lot of goods and services probably would be coming from Texas and Louisiana and other Gulf Coast states,” he said. “A lot of the services that are basically required to operate drilling rigs and production platforms, you have to have that locally.”

Oil Rig Jobs

Deep-water rigs hold a workforce upwards of 400 people – engineers, drillers, welders, floor hands, machinists, mechanics and cooks to name a few. Then there’s the supply stream –truck drivers hauling equipment to and from ports, offshore vessels to get supplies and equipment to the rigs, fabrication facilities to provide steel pipes.

“There’s a lot of different jobs,” said Patrick Courreges, communications director for the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. “If you’re in Louisiana you’re in the oil and gas business because this one industry touches everything. It doesn’t even matter if you have a furniture store – you’re in the oil and gas business.”

He recalled the six-month deep-water drilling moratorium imposed in 2010 after the BP accident that killed 11 workers and spewed nearly five million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

“You could feel it,” he said. “It affected even real estate because people tightened their wallets.”

In an effort to secure an oil and natural gas workforce in the mid and south-Atlantic states, U.S. Mark Warner, D-Va., recently submitted a bill that would, in part, secure funding for higher-education aimed at offshore energy resources.

The proposed Southern Atlantic Energy Security Act would require 2.5 percent of state-allocated funds to be used on a public-private partnership between industry, schools and historically black colleges and universities to “enhance and broaden” geological and geophysical sciences and new studies of offshore energy resources. The bill calls for each state’s governor to nominate participating schools.

A Closer Look

Doug Wakeman, a professor of economics at the Meredith College School of Business in Raleigh and a member of the N.C. Coastal Federation’s Board of Directors, breaks down Quest’s data in his report “The Economics and Uncertainty of Offshore Drilling.”

“There’s a question of how many of those jobs that are created would be filled by people already in North Carolina as opposed to people who would migrate in.” he said. “It’s a matter of where they actually expect to be most successful in terms of drilling. The places where the most attractive oil deposits are is fairly well north along our coast. Does that mean oil production and those jobs would go to more to places like Virginia Beach and the Norfolk area?”

The future price of oil is also a critical factor in trying to determine the economic benefits of drilling for the state, Wakeman explained. Higher prices not only mean greater profits for the oil companies, he said, but they also encourage drilling in economically marginal places.

When oil sells at $120 a barrel, as it did a couple of years ago, deposits that are expensive to drill, such as those in the deep-water Atlantic, are profitable, Wakeman said. They become less profitable as the price drops. He notes.

The Quest report uses federal estimates to predict the future price of oil, Wakeman said, but it’s unclear what range of prices through 2040 was use – high, low or a median.

“All economic estimates in the API report may be regarded as overestimates,” he writes.

The Quest report and industry proponents suggest untapped natural oil and gas resources in the Atlantic could prove to be huge – 1.34 million barrels of oil equivalent per day by 2035.

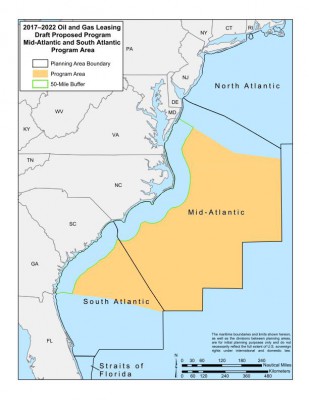

That report was released in December 2013 before the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, announced its proposed leasing program for the mid-Atlantic.

The 2017-2022 offshore oil and gas leasing program unveiled in January includes a 50-mile barrier and one lease sale in 2021 in federal waters off the Atlantic coast stretching from Virginia to Georgia.

Quest’s report does not include the 50-mile buffer, assumes leasing in the mid and south Atlantic would begin in 2018 and does not include the single lease sale cap.

Those restrictions have an effect on the numbers in the Quest report, which has been routinely cited by politicians, including Gov. Pat McCrory.

Shafer said the unaccounted restrictions in the report will have some effect, but “I don’t know that it would be significant,” he said.

After running the numbers factoring in the 50-mile buffer, 38 percent of reserves would be excluded off the North Carolina coast, he said.

“Sixty percent could still be tapped,” Shafer said. “You never really know until you drill. More likely than not we’ll likely see more oil than has been suspected.”

That’s not necessarily the case, Wakeman said.

“Nobody knows for sure how much oil and gas is in the ground,” he said. “The API report simply assumed that the amount of oil there that would be found with new technology would mimic what’s been found in other places.”

API at this time has no plans to update the numbers.

“Ideally we would be able to update it to have it exactly reflect what the BOEM draft proposed plan was,” McGowan said. “At this point we’re going to wait and not update it. I think the concept still applies that North Carolina has the potential to benefit more than any other state in the mid-Atlantic. You’ve got the potential number of lease sales that could change. You’ve got the timing of the lease sales that could change. What we would assume is they’ll do a lease sale in 2021 and probably another in 2023. It would probably make the region a lot less attractive if they have to wait until 2030. I don’t think it’s possible for there to be just one lease sale.”

That’s what supporters of offshore drilling, including McCrory and U.S. Sen. Tom Tillis, R.-N.C., hope to revise through Congress, though the Obama administration is making clear its opposition to such changes.

In a March 30 letter to U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, McCrory urged the buffer be changed to 30 miles, that the proposed lease sale date be moved to earlier in the five-year program and that a second lease sale be added to the end of the program.

Whatever the case, consumers aren’t necessarily going to notice a difference at the pump. Though nearly all domestic oil is kept in the U.S. the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Counties still sets gas prices.

Consumers in Alaska, which has the lowest gas tax in the country, still pay about 50 cents more per gallon than in North Carolina. Gas prices in other oil producing states like Texas and Louisiana aren’t much cheaper than what North Carolinians pay for today.