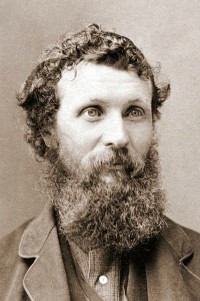

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” – John Muir

SMYRNA — When Scottish-American naturalist and author John Muir penned those words in My First Summer in the Sierra, published in 1911, he aptly described the potential impact of tugging on one thread of the grand quilt that is a natural ecosystem: the whole thing can come unhitched.

Supporter Spotlight

Agricultural operations, cleared of trees, crisscrossed by drainage ditches and filled with rows of non-water-dependent crops, do that to coastal wetlands. But, the N.C. Coastal Federation has been trying to “re-hitch” North River Farms to its surroundings in Down East Carteret County since 1999 – buying and restoring the farm to its former wetlands habitat – and one of the final phases is set to begin.

Over the next month or so, the environmental group plans to plant more than 300,000 seedling trees on a 1,020-acre tract near the entrance to the farm, just off U.S. 70 near the turn-off to Harkers Island. It’s the last tract on the 6,000-acre farm to be restored because the previous owner of the farm, Jimmy Winslow, was given time to wind down his farming after the federation purchased the property.

“It’s the beginning of the end” of the project, said Lexia Weaver, the federation’s coastal scientist who oversees the project. “When we purchased the property, he had 10 to 12 years under a lease. Now it’s time to get to work.”

Already, much of the farmland has been altered. Drainage ditches have been plugged to keep stormwater runoff from flowing into the shellfish waters of North River, Ward’s Creek and Jarrett Bay. While those changes dramatically reduced the runoff and led to better water quality, the planted trees will take up much of the remaining water and filter out more pollutants. And as they grow, the bald cypress, swam black gum, water tupelo, green ash and oaks will become prime habitat, not only for countless birds but also for deer, coyote and other mammals.

Although the federation sometimes recruits volunteers to plant marsh grass and tree seedlings, this phase of the massive North River Farms wetlands restoration effort is just too big for that. These trees will be planted by machine. There will, after all, be 302 trees per acre; and they’re supposed to be planted in precise grids to allow for easier landscaping, when it becomes necessary.

Supporter Spotlight

A certain amount of undergrowth is good, Weaver said, but it’s important from a biological perspective for it not to get too thick, and since the money is coming from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, strict guidelines must be followed. Some undergrowth will be sprayed and killed, but only when conditions are right and the trees are dormant.

“The ultimate goal, of course, is to restore the wetlands function, but we’re also doing this whole project to create habitat for wildlife,” Weaver said. “And it’s been working very well. John Fussell (local ornithologist) has already seen many birds here that he hadn’t seen before, and we’re seeing lots of deer and even some coyote.”

Water quality around the 6,000-acre former farm is also improving, she said, as some of the shellfish water closure lines have been adjusted slightly upstream; water sampling has shown lower counts of coliform bacteria, which is the standard the state uses for opening and closing waters for harvest of oysters and clams.

Word from fishermen also has been positive, Weaver said, with credible reports of better catches than in the recent past and the return of certain fish that haven’t been seen in years.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done,” Weaver said, “but the end is in sight. We’re probably about a year-and-a-half from completing the whole 6,000 acres. It’s exciting.”

But the near-end is also a near-beginning. The federation’s vision for the land includes opening much of it to the public. Bird-watching, of course, will be excellent, and school groups will be able to use the property for science and ecology classes. University research will also be allowed to continue. The federation even plans to allow some hunting.

“I won’t be every day,” Weaver said, “but it will happen. You don’t want the property to be overrun – we’re definitely concerned about safety, too – so we’ll probably have a lottery of some sort to let people in.”

If things pan out as planned, she added, a limited amount of hunting shouldn’t be bad for the wildlife populations, and the income from permits will help pay the cost of maintaining the property’s infrastructure, including the roads.

“Use by the public is an important part of the project,” Weaver said. “There will be nature trails and places that are good for hiking. We are hoping that some areas will be open to the public within a couple of years, maybe sooner.”

The project is one of the largest of its kind in the nation, and the habitat restoration promises to be a major attraction for birds and animals. Last year, for example, Wes Newell, owner of Backwater Environmental, a partner in the effort, said he expects it will someday attract up to a million snow geese. Newell’s company finished restoring the 385 acres it owns – 60 acres of forest and 325 acres of wetlands — and planted 150,000 trees.

The whole effort, Weaver said, began way back in 1999 when the federation bought 1,991 acres of land at North River Farms for $1.07 million with a grant from the state’s then-thriving, taxpayer-funded Clean Water Management Trust Fund. That acreage has long been restored. And in 2002, the federation bought another 2,168 acres for $3.01 million with more funds from the state trust fund.

That same year a hunters’ group purchased 1,435 acres of the farm with the intention of enrolling in the federal Wetlands Reserve Program. That land is also now restored and is home to growing numbers of waterfowl. Also, a private mitigation bank company, Restoration Systems, LLC, purchased 385 acres of the farm. It’s this purchase that ended up in the hands of Backwater Environmental, which also does mitigation work, helping balance the environmental damage done by, for example, highway construction projects.

Newell said that he was proud to participate in the project last year as company began restoring its tract of North River farms. He called it the only opportunity on the East Coast to create a whole “new” ecosystem. When it’s all finished, up to 5,100 acres of the 6,000-acre farm will have been restored to wetlands.

Weaver pointed out that many other agencies have supported the project financially, providing grants and expertise. Among them are the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the EPA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the FishAmerica Foundation, the N.C. Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Program and the N.C. Wetlands Restoration Program. Universities, including N.C. State, have also been involved, through planning, design, research and monitoring.

All involved have consistently praised Winslow, the farm’s prior owner, for his participation. He could have sold North River Farms, or portions of it, to someone who’d have used the flat, by-then mostly dry land for residential or even commercial development; but Winslow decided he wanted to go the natural route and create wildlife habitat and help stop the pollution that had contributed to the state-required closure of countless shellfish beds over the years.

The entire North River Farms project will eventually involve the planting of more than 1 million trees and other wetlands plants.

As Muir, the father of the nation’s national park system said in John of the Mountains, published in 1938: “The wrongs done to trees, wrongs of every sort, are done in the darkness of ignorance and unbelief, for when the light comes, the heart of the people is always right.”