The N.C. General Assembly is looking into the possibility of the state acquiring the Oregon Inlet and the adjacent land. Pictured left of the Oregon Inlet is northern Bodie Island, which is part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore; and to the right is Hatteras Island, which is part of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Army Corps of Engineers |

RALEIGH — A legislative task force is hurrying to meet a May 1 deadline for a report on the potential state takeover of Oregon Inlet and adjacent land on the Outer Banks in Dare County. Meanwhile, the inlet is again showing how cantankerous and unruly it can be to whoever wants to try and corral it.

The Army Corps of Engineers last week raced to get a shallow-draft dredge in place to start clearing the inlet, which had become nearly impassible after the Corps spent $7 million three months ago to open a 15-foot deep channel. Plans are to bring in progressively larger dredges after that to open it back up to navigation ahead of the spring and summer fishing seasons.

Supporter Spotlight

Cost estimates aren’t in but the work is likely to suck up a sizable portion of the $800,000 set aside for the Manteo region in this year’s federal dredging budget. In an era of shrinking federal budgets, the annual cost of keeping the inlet open to larger boats is estimated to run up more than 10 times that amount in the future.

The plan to come up with a state-run solution to the inlet is another attempt to break what members of the Oregon Inlet Land Acquisition Task Force see as a death spiral for the waterway. The N.C. General Assembly created the study group last year to look into the possibility of the state acquiring the inlet and adjacent land on Hatteras and Bodie islands. With the land in hand, the state would then presumably take steps to control shoaling in the inlet, such as resurrecting the old plan to build jetties on either side of it. The federal government now owns the land, which is part of a national seashore and wildlife refuge, and claims ownership of submerged land in the inlet. It killed the jetty proposal in 2003 after decades of debate.

As difficult as it may be to come up with a viable plan for the state to own and manage the inlet, cutting a deal with the feds to make it happen may be even harder

Discussion with the federal government over a potential land swap or sale of Oregon Inlet will start at the cabinet level, according to Department of Administration Secretary Bill Daughtridge, who chairs the task force.

Bill Daughtridge |

At its most recent meeting on March 26, Daughtridge told task force members he would lead the effort to gauge federal interest in the project and would likely take it directly to Sally Jewell, Department of Interior secretary.

Supporter Spotlight

A department spokesman last week said that there’s been no official contact with the task force, but that National Park Service officials know about the effort. The park service is part of the Interior Department.

“We’re certainly aware of it,” said William Reynolds, a spokesman in the National Park Service’s regional office in Atlanta. “The park service is aware of the activity and aware of the task force.”

Reynolds said the department is taking a wait-and-see approach. “From the federal government’s perspective, the issue was resolved in 2003,” Reynolds said. “We can’t speculate on what the task force will propose and we wouldn’t want to speculate on what impact that might have.”

Reynolds said transferring park land is not common but does happen. The boundaries of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, he noted, are included in the bill that created the country’s first national seashore in 1937. Only Congress, he said, can change those boundaries.

“It would take an act of congress to change the boundaries of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore,” he said.

Joshua Bowlen, legislative director for Rep. Walter Jones, R-N.C., said Jones is aware of the task force’s effort, “but only from 10,000 to 30,000 feet.” His district includes Dare County.

Jones supported the bill to study acquiring the land and inlet, he said, and sent Gov. Pat McCory a letter last fall urging him to set up the task force.

Bowlen said Jones supports the concept of transferring ownership to the state and would introduce a bill in the U.S. House changing the park boundaries if the state came up with a viable plan.

The task force is scurrying to do just that. The 11-member group of administration officials, representatives of Dare County and coastal legislators, is hurrying to finish up a report by the end of April. It is scheduled to meet again April 25 in Manteo to go over a draft report on the economics, legal, environmental and transportation aspects of assuming ownership and management of the inlet.

The Currituck dredge will arrive next week to remove sand from the Oregon Inlet. Only three months ago the Army Corps of Engineers spent $7 million to open a 15-foot deep channel. Photo: Outer Banks Voice |

Since it started meeting in January, the task force has been trying to build mainly an economic case for a state takeover, which includes the construction of jetties that were rejected by the White House Council on Environmental Quality in 2003. The end of the jetty option, however, came with a guarantee that the Army Corps of Engineers would maintain the inlet, but federal money for dredging has been dropping.

Daughtridge, a former legislator from Rocky Mount, said it will be important to show Department of the Interior officials that the plan would lower the long-range cost of maintaining the inlet.

“If you reduce the cost of dredging, you affect the federal budget,” Daughtridge told the task force in March. But coming up with a viable plan is not proving easy, especially given the fast approaching deadline.

While the legislation that set up the task force did not include the jetties and a sand management plan, members are trying to build a case for a combination of jetties and regular dredging.

At last month’s meeting, Daughtridge told task force members that they will have to look elsewhere to back up their case because federal officials have already rejected an economic argument based only on commercial fishing. Most of the commercial boats have left Wanchese because of the danger of going through the inlet.

They intend to use analysis from an updated report on the economic effects of the inlet being prepared for the Dare County Board of Commissioners. The analysis, due in early May, updates a 2006 report prepared for the county which put the total annual effect of the inlet on charter and commercial fishing, boat building and tourism at roughly $683 million.

Another key part of the task force’s economic argument focuses on the negative effects of a closure or partial closure of the inlet on inland flooding, saltwater contamination of farmlands and wetlands and estuaries.

Record keeping for the task force has not kept up with the pace. The Department of Administration set up a web site in March but so far has only released minutes and presentations from one meeting. Secretary Daughtridge declined to be interviewed for this story. In an email response to an interview request Chris Mears, a spokesperson for the department, said, “Because we are still in the information gathering stage, we aren’t ready to accept interviews. We’ll be more than happy to once we have all of our information together.”

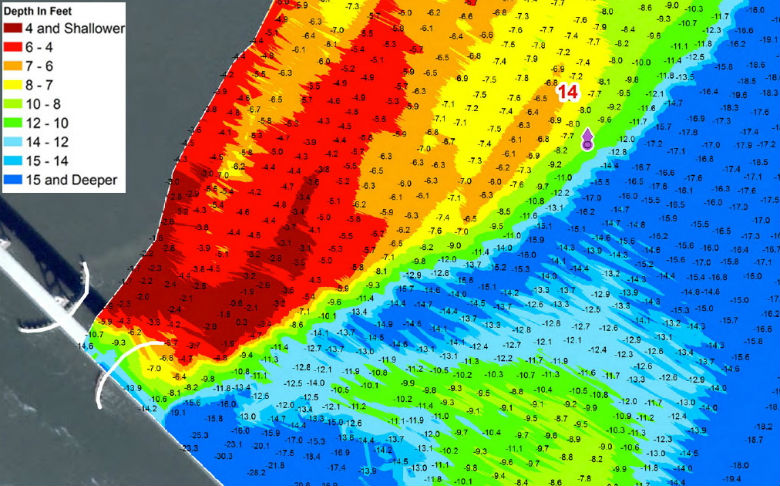

This survey from early April shows the depth of water by the Herbert C. Bonner bridge over the nearly impassable Oregon Inlet. The deep red color shows where there is 4 feet or less of water, the brighter red 4 to 6 feet of water. Source: Army Corps of Engineers |

Stan Riggs, an East Carolina University geology professor and researcher who has a long history with Oregon Inlet and the Outer Banks, said the state probably could come up with a dredging plan that could keep the inlet open at a reasonable depth. The danger, he said is trying to “over-engineer” a solution to maintain it for bigger and bigger boats.

Riggs said he sees a tremendous financial risk in the state taking over the inlet and trying to build the jetties.

“I’m afraid this is just the beginning of an economic nightmare,” he said. “Oregon Inlet never was a deep-water inlet and never will be, even with their jetties.”

In addition to dredging to maintain the inlet, he said, there will be additional costs to maintain the beaches to the south as the jetties cut into sand flow. “This would be an incredible long- term investment,” he said.

With federal dollars dwindling and the state and local governments all along the coast having to take up the slack, a costly project at Oregon Inlet would eat up a lot of money every year, Riggs said. “The state just doesn’t have the resources to deal with all of this,” he said.

Stan Riggs |

Riggs also agreed with a preliminary analysis for the task force by the Department of Environment Natural Resources, which sent a memo to Daughtridge that shot down some of the assumptions about the likelihood of the inlet closing and its effects. In response to concern about inland flooding the memo states:

“There would likely not being a significant increase in the likelihood of inland flooding due to a closure or restriction of Oregon Inlet. Significant rainfall impacts these low lines regardless of Oregon Inlet’s status. A hurricane or nor’easter would likely open a new inlet if Oregon Inlet remained fully close.”

The memo also downplays the potential impact on farmland for the same reason.

Riggs said assuming the inlet would close is too simple.

“The number and size of inlets are a function of storm patterns,” he said. “They’re intimately tied to storms and storm dynamics. I don’t think it would close. It’s the only one in the northern area.”

Storm dynamics and wind conditions work to keep the sand flowing out as well as in, he said. “It’s a self-adjusting and self-regulating system.”

In fact one thing that could stop the natural flow of sand out of the inlet and create problems inland, he said, are jetties, which would slow down water flowing from Pamlico Sound. “The inlet, he said, needs to breathe.”

Layered over the debate, he said, is the how much can change even in a short period of time. In the late 1980s, he said, the inlet moved 1,000 feet in one year. And any solution has to take into account that one storm could change the dynamics very quickly.

“(Hurricane) Sandy could have been our storm,” Riggs said. “If Sandy had come ashore we wouldn’t be talking about any of this.”