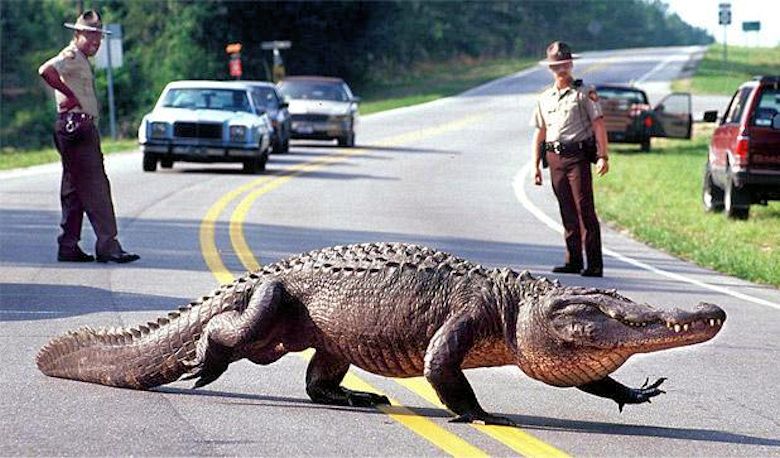

Why did the alligator like this one in Brunswick County cross the road? Because it wanted to. The first alligator survey in North Carolina in 30 years should help determine if human interactions with alligators are getting more frequent because the animals are more abundant.

Supporter Spotlight

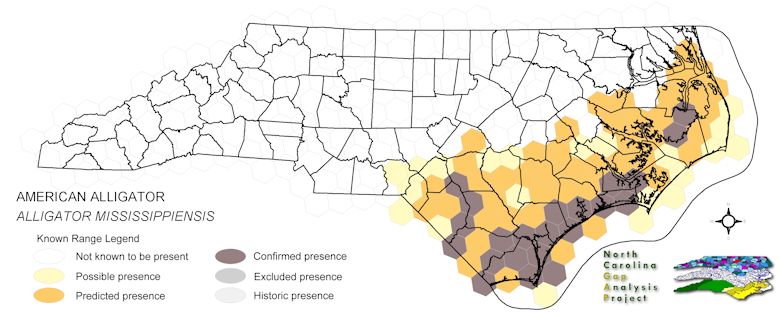

American AlligatorClassificationClass: Reptilia Order: Crocodilia Range and DistributionThe American alligator ranges from coastal North Carolina to southern Florida and west to central Texas. They inhabit the swamps and shores of North Carolina from Brunswick and New Hanover counties north to the Alligator River Wildlife Refuge in Hyde County. The largest populations live in the southernmost counties, but healthy populations also live near the lakes of the Croatan National Forest in parts of Carteret, Craven and Jones counties. Average SizeMales: 11 to 12 ft., 450 to 550 lbs.; females: about 8 ft., more than 160 lbs. FoodYoung alligators eat insects and crustaceans. Adult alligators eat fish, snakes, frogs, turtles, mussels, crayfish, birds, muskrats and many other kinds of small animals that live in or near the water. They feed primarily at dawn and dusk. Supporter SpotlightBreedingNesting begins in June. One brood a year. Female may not breed each year. Lays about 30 eggs. YoungHatchlings protected for up to two years by mother. Life ExpectancyAbout 15 years in the wild. StatusIn 1967, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protected this alligator by classifying it as an endangered species. Some populations prospered, enabling its classification to be changed to Threatened in Florida and other coastal regions such as North Carolina. Source: North Carolina Wild |

RALEIGH – Lindsey Garner’s summer plans probably did not look like most North Carolinians. Armed with a flashlight, this N.C. State University graduate student spent her nights for the past two summers in many of the rivers, lakes and estuaries of North Carolina coast, looking for the reflective glare of a pair of alligator eyes.

If the idea of an alligator in North Carolina is a surprise, you aren’t alone. Though not as common as in the warmer and more tropical environment of Florida or Louisiana, the American alligator is native to North Carolina, where it is a federally protected species.

“They aren’t like the coyote that slowly expanded its range. Alligators have always been here,” said Garner, noting that there are written accounts of alligators in North Carolina for at least the past 150 years.

But just how many alligators are there in the Tar Heel state? This is the question that drove Garner, in conjunction with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, to conduct the first census of the N.C. alligator population in 30 years.

“We were trying to replicate a study done in 1980,” said Garner.

Lindsey Garner hams it up with a fake alligator. Photo: NCSU |

Survey routes extended from the Virginia border all the way south to the South Carolina border. “Most of the surveys were about ten miles, or in the case of lakes we surveyed the entire perimeter. So we covered a very large area,” explained Garner, who helped complete 100 surveys over the past two summers.

In order to get the best estimate of the population size, Garner and her colleagues concentrated their efforts to coordinate with the alligators’ breeding season in June and early July, when the animals congregate in tighter densities.

As Garner explains, “Once July hits the females retreat to the mudflats, estuaries and swamps, away from open water to nest.”

Any qualms about being on the water with a bunch of alligators during their breeding season are brushed off by Garner. “I personally had no worries,” she said. “The males are more territorial during this time, so maybe for the alligators this is a more dangerous time, but for people what you really want to avoid is a nest.”

A nest or an alligator that has become too accustomed to humans.

It is true that human-alligator interactions are becoming more common. In July, a 12-foot alligator killed an 80-pound Siberian husky near Jacksonville. The attack occurred in an area that is near both commercial and residential buildings, leading some to believe that this was likely an animal that had been fed by humans. The alligator was killed and will eventually be displayed at the Onslow County Environmental Education Center and Library, with the hopes that it will teach visitors about the importance of maintaining safe boundaries between humans and wild animals.

Garner lets out a sigh when the attack is mentioned. It is obviously not her first time answering questions about this incident, nor is it something she wants to be the focus of a conversation about the population of alligators living in the state. And why should she? There is – understandably — fear and anger when a wild animal attacks a pet or a person, but when you consider the opportunities that exist for more of these attacks to occur that simply don’t, it is understandable why Garner sighs at the inevitable question of how much danger these animals pose to humans.

“That was an unfortunate event for the dog and the alligator,” Garner says earnestly.

She is hesitant to discuss the incident in much depth, but she does mention that all indications were that this was an animal that had been taught to lose its fear of humans.

In South Carolina, people are warned about feeding alligators. |

She also notes that a 12-foot alligator is not a common occurrence in North Carolina. “They do get that big in the state, but it is pretty rare for that to happen. They grow half as quickly here as they do in Louisiana, where they have the fastest growth rate.”

This variation in growth rates largely has to do with the temperature differences within the natural range of the species. The relatively colder temperature in North Carolina cause the alligators to grow much more slowly and leaves them vulnerable to predation for larger portions of their lifespan than their counterparts in other, warmer, states. This is one of the reasons that the population size in North Carolina is smaller than in other Southern states.

The estimate of what the population size actually is has not yet been analyzed, and Garner is careful to note that this was primarily a density study to see “where they did occur and didn’t occur.” The goal of the study was to obtain a 30-year trend to see if their distribution and range have changed since the previous census.

“We want to see if the population has increased, decreased or if people are just running into them more,” explains Garner.

Preliminary analysis shows that, similar to 30 years ago, alligators don’t generally occur north of the Albermarle sound, and that the greatest densities of alligators are in protected areas such as Croatan National Forest along the central coast and in the areas around Wilmington.

“Distribution seemed to be about the same [as30 years ago]. There are very low densities throughout rivers and estuaries, with pockets of high densities dispersed throughout eastern North Carolina,” said Garner. “Alligators [population] generally increase the further south and the closer to the coast you get.”

What Garner is certain of is that alligator population densities in North Carolina are much lower than in the more southern populations.

Still, Garner wants people to know that there are alligators out there. “People should be aware that there are alligators in the state, or at least in eastern North Carolina. They are there,” she said. “And what is also very important is that you should never feed an alligator, because that happens a lot. They will mind their own business and stay away, unless they are being fed.”

Garner and her colleagues hope to have the final analysis completed by December.

More information about the population census completed in the 1980’s can be found in the paper by O’Brien, Timothy G., and Phillip D. Doerr. “Night count surveys for alligators in coastal counties of North Caroline.” Journal of Herpetology 20.3 (1986): 444-448.