Lighthouse ScheduleThe National Park Service will offer guided tours of the Bodie Island Lighthouse until Columbus Day in early October. The tours will run from 9 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. daily. Tickets are $8 for adults and $4 for people over 62, children 11 years of age and under and those holding a National Parks and Federal Recreation Lands Access Pass. Tour tickets may be purchased at the lighthouse on the day of the tour or may be reserved in advance. Supporter SpotlightTours start every 35 minutes and are 45 minutes long. Each guided tour is limited to 22 people. Children must be at least 42 inches tall. Children under 12 must be escorted by a person at least 16 years old. The lighthouse will only close to climbing when there is lightning, high winds or a heat index of 103 or above. The Park Service warns that the climb is strenuous. There is no air conditioning. It may be noisy, humid, hot and dim inside the lighthouse. Visitors with heart, respiratory or other medical conditions, or who have trouble climbing stairs, should use their own discretion as to whether to climb the tower. For more information, visit the Bodie Island Lighthouse Web site or call 252-441-5711. For climbing reservations, call 252-475-9417. |

NAGS HEAD — After nearly four years of restoration work and $5 million, Bodie Island Lighthouse opened to the public for climbing on April 19 for the first time in its 141-year history.

Supporter Spotlight

Although that morning was chilly and rainy, all 352 available tickets for the free climb were given out by noon. People will be able to climb the lighthouse every day until Columbus Day but for a fee.

Bodie Island offers “one of most commanding views from an Outer Banks lighthouse,” said Charlie Kolb, lead interpreter for Bodie Island District of the National Park Service. “It’s all water—the ocean, marshes, sound.”

Kolb said he and his staff won’t be surprised if tours are full all summer.

Four miles north of Oregon Inlet, 156-foot-tall Bodie Island overlooks Cape Hatteras National Seashore. This means it stands as “one of the few U.S. lighthouses where the view is very close to what it would have been,” noted Joel Proper, the park ranger who led my one-person tour on an overcast morning a few days after the official opening.

Stepping inside the lighthouse through the original thick wooden door, Proper showed me the room to the left where lighthouse keepers once greeted guests and the room to the right where barrels of kerosene oil had been stored.

Stepping inside the lighthouse through the original thick wooden door, Proper showed me the room to the left where lighthouse keepers once greeted guests and the room to the right where barrels of kerosene oil had been stored.

Kerosene was the main fuel for the light over the years, although whale oil, rapeseed oil and even lard had previously been tried.

“Keeping lard warm was a challenge,” Proper noted.

Bodie Island got full electricity in 1932, and the lighthouse’s characteristic—2.5 seconds on, 2.5 off, 2.5 on, 22.5 off—has been the same ever since. The light is visible for up to 19 miles.

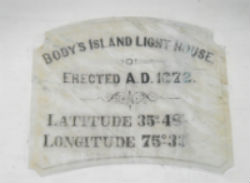

Inside the lighthouse base, a plaque reads, “Body’s Island.”

Folklore insists that a family named Body once owned the surrounding land, but nobody really knows. Proper prefers another explanation—the human bodies that continually washed ashore with the tides.

“There were more shipwrecks off the N.C. coast per square mile than any other coast in the world,” he said. “In 1872, when they referred to it as ‘Body’s Island,’ there could be a connection.”

On that note, we began our ascent. The 40-mile-an-hour wind was a persistent echoing presence. Stopping for a quick rest on a landing, Proper pointed out visible former cracks in the walls that had been re-grouted and painted during renovations.

The historical recipe of lime paint recipe was researched and is now again being used on the walls at Bodie Island, he said. Latex paint was previously used, which did not allow the bricks to breathe.

At the top, the door to the balcony was open and wind gusts howled in. Proper and I spoke of respect for lighthouse keepers making that climb during hurricanes and other strong storms that would bring easily double the wind speed.

The view was majestic. It reaffirms that here, the water defines the land.

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration added the sand dunes—a lightly colored, curvaceous stretch by the tumultuous Atlantic today—in an attempt to contain the ocean, and Duck Pond immediately below was dammed by the nearby hunt club to create waterfowl habitat.

But not much has changed since Cape Hatteras National Seashore was established in 1953.

It took three attempts for Bodie Island Lighthouse to remain standing.

Ascending the Bodie Island Lighthouse is like climbing a 10-story building, but you’re rewarded with a stunning view. Photo: Corinne Saunders |

The first quickly started resembling the Leaning Tower of Pisa because of an unstable foundation. It was built in 1848 by the early Lighthouse Board, comprised of ship captains, not engineers, Proper explained, and was soon abandoned.

The second lasted from 1859 to 1861, when Confederate troops retreating to Roanoke Island blew it up so Union soldiers wouldn’t have the vantage point.

The first two lighthouses were south of Oregon Inlet, but because Oregon Inlet itself was moving southward, the third was built to the north and was completed in 1872.

It is a twin of Currituck Beach Lighthouse; both were built according to the same architectural plans, including the 214 steps in each, and just given different light patterns and paint jobs.

Bodie Island was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939, then to the National Park Service in 2000.

Two large cast-iron chunks fell from the top of the tower in 2004. There were no injuries, but the base of the tower was closed.

Restoration work began in 2009, with initial funding of $3 million.

The light was turned off for the first time in its history, and the lighthouse was found to have settled only two inches in 141 years.

Developed by French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, the first-order Fresnel lens is the biggest of all lighthouse lenses, standing 12 feet tall and with an interior diameter of more than six feet. It was removed so all 344 multi-faceted glass prisms could be cleaned and its metal pieces could be adjusted.

Additionally, during renovations, all the metalwork on the balcony and inside the lighthouse was fixed and repainted.

The climb up the spiral staircase is strenuous,the Park Service warns. Photo: Corinne Saunders |

Rusted stairs were taken to a foundry, where stronger alloy was added to the melted metal. The stairs were recast, but because the original metal remains in them, “we can still call them historic stairs and maintain the 1872 connection,” Proper said.

As paint was peeled off lighthouse walls, cracks became evident, and funds were insufficient to repair everything.

After a new assessment, a $1.89-million contract was awarded to United Builders Group of New Bern, which began the second renovation in March 2012.

Thus, the elaborate scaffolding required to renovate Bodie Island had to be put up and taken down twice.

Cracks were re-grouted, the windows were all replaced and support beams under the balcony were strengthened. Stairs were strengthened where they are bolted to the wall, electrical lines were replaced, a fire detection and suppression system was installed and marble flooring was repaired in the oil house.

Ascending Bodie Island Lighthouse is “equivalent to climbing a 10-story building,” said Patrick Gamman, district interpreter for Hatteras, Ocracoke and Bodie Island. “In our culture, if it’s over two stories, we take the elevator.”

At Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, a 12-story climb, three to four people have to be carried down each year. As many as 1,400 to 1,500 visitors climb each day in the summer.

Unlike Hatteras, Bodie Island won’t have self-guided tours. With a ranger setting the pace and safety talks before the climb, Gamman expects more anxiety walk-outs, but few or no carry-outs.

The Park Service will follow the engineers’ recommendation to set a maximum number of 380 climbers a day at Bodie Island.