North Carolina will likely tighten its recreational swimming standards this year at some places along the coast in response to new water-quality guidelines by the Environmental Protection Agency.

State and EPA officials say the changes will not be significant to the state, where the current rules for notifying the public of potentially harmful bacteria in coastal waters is more stringent than that of the new guidelines.

Supporter Spotlight

“From our program standpoint, not a lot is going to change,” said J.D. Potts, manager of the Recreational Water Quality Program at the state Division of Marine Fisheries.

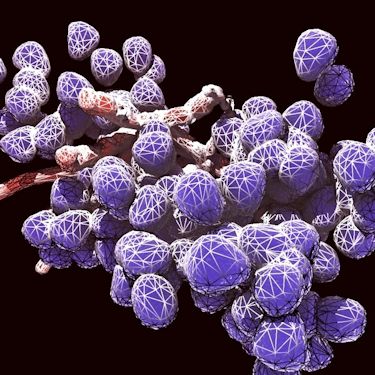

The state’s current limit for the amount of enterococcus, a bacterial organism commonly found in the intestinal tracts of warm-blooded animals, is a single-sample maximum of 104 enterococci per 100 milliliters of water in what the state classifies as Tier 1 sites.

Here’s a 3-D rendering of an enterococcus bacteria colony. Photo: Michael Taylor 3D |

All ocean sites are ranked Tier 1 – water used by the public on a daily basis. Of the 240 swimming sites the state regularly tests, 92 are classified Tier 1.

“If you look at the numbers for marine waters the new criteria is actually a little more lenient,” Potts said. “We’re using 104. It is now a 130. We will probably just continue on with the 104. We are pretty much doing what they’re asking.”

The only significant change the state is expected to make is setting the measurement of 104 enterococci per 100 milliliters of water as the guideline for its Tier 2 and Tier 3 sites, Potts said.

Supporter Spotlight

“We will eventually go to the 104 at all sites,” he said. “That’s basically the main difference.”

Tier 2 waters are classified as those visited by people an average of three times a week. There are 104 Tier 2 sites tested in the state. The current standard for Tier 2 waters is 276 enterococci per 100 milliliters of water.

The third tier includes waters used an average of four times a month. The single-sample maximum level of enterococci is 500 per 100 milliliters of water in this tier. The state has 44 Tier 3 sites.

The state’s Recreational Water Quality Program began testing coastal waters, including ocean beaches, sounds, bays and estuarine rivers, in 1997. Testing is designed to prevent the public, including the tens of thousands of tourists who visit the beaches along North Carolina’s 300 miles of coastline each summer, from contracting illnesses caused by coming into contact with bacteria, including E. coli.

Most sites are tested on a weekly basis during swimming season – April 1 through Oct. 31. Ocean beaches and “high-use” sound-side beaches are tested weekly from April through September. Each site is tested bi-monthly from November through March. About 6,000 samples are collected in the state each year in swimming areas from Currituck County down to Brunswick County.

The EPA’s new recommendation suggests samples be collected at least weekly and that the results be evaluated within 30 days. The agency has also approved a faster method for water monitoring, cutting down the time it takes to process results.

The state posts swimming advisories at sites where bacteria samples indicate higher levels than the maximum standard. In water where an advisory is issued from a single-sample exceeding the maximum limit the site will be re-sampled each day and a sign will remain on site until levels fall within safe regulations.

If a sample exceeds the geometric mean of 35 enterococci per 100 milliliters, a swimming advisory is not lifted until two consecutive weekly samples meet the standard.

Some of the most common enterococci-producing culprits in recreational waters include waterfowl, such as ducks and geese. Sources of human fecal contamination include stormwater runoff, poorly treated wastewater from treatment plants and malfunctioning septic systems.

In 2011, 22 advisories were posted. The year prior, the state issued 23 advisories. Due to higher levels of rainfall in 2010, which contributed to greater amounts of storm water runoff, 45 advisories were issued.

“Now there’s a little switch up so we’re going to have to go back and change some things but I don’t see the program having any more or less advisories,” Potts said.

The EPA bumped up its guidelines in November in response to a federal court order and a requirement of the Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act of 2000.

N.C. Beach Tier Designations

|

New guidelines are based on several health studies that link bacteria in coastal and inland waters to a wider array of illnesses than previously recognized.

The agency has two measurement standards, one that allows for higher concentrations of bacteria in the water and one that limits the acceptable concentration of water-borne bacteria.

The two-fold guidelines are prompting criticism from some environmental groups that argue states may choose the less stringent of the two thresholds.

The new standards, updated from those last issued in 1986, are expected to reduce illnesses down from 36 to 32 per 1,000 people, according to the EPA.

Joel Hansel, an environmental scientist with the EPA’s Region 4, which includes North Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina and six American Indian tribes, said he anticipates most states within the region adopt the new standards.

“Over the next year we’re going to be producing implementation guidance to the states,” Hansel said. “We typically see in three to five years states pick up any recommendation we make. The North Carolina program is right on par with them.”

The Great Lake states and all coastal states currently have the 1986 criteria in place, some adopting the changes at their own accord and some because the EPA promulgated them to do so as part of the congressionally-approved 2004 Beach Act. Most states, including North Carolina, will see only a slight change, Hansel said.

“For the inland waters, that’s a little different,” he said.

Some inland states use criteria set back in the 1960s.

“I think it’s going to get a little tumultuous for them to change,” Hansel said. “But I think the handwriting is on the wall that this is inevitable. I think there’s going to be some pressure for them to be changing more. The criteria are really minor changes when it comes right down to it.”