Last of two parts

RALEIGH — A group of 85 doctors and medical professionals recently wrote Gov. Beverly Perdue expressing alarm that state lawmakers were considering weakening or dismantling the state’s air toxics program.

Supporter Spotlight

“Now is not the time to weaken North Carolina’s air toxics program,” said, Dr. Lawrence Raymond, chair of the Medical Advocates for Healthy Air. “Having more toxic pollutants in the air we breathe will only diminish our state’s appeal and will certainly decrease public healthy, especially for children, seniors and those with medical conditions.”

Dr. Lawrence Raymond |

Republican legislators in the GOP-controlled N.C. General Assembly are considering changes to the state’s 20-year-old program that would exempt North Carolina’s largest polluters of dangerous airborne chemicals from meeting state standards that are meant to protect people’s health.

If the legislative majority’s “reckless attack” on the air toxics program is successful, the doctors wrote, the changes will be paid for by personal health tragedies and medical expenses by many families in North Carolina. Exposure to air toxins is linked to cancer, pediatric respiratory disease, adult respiratory and cardiac disease and premature death. Children, pregnant women and seniors are most at risk of harm from industrial emissions.

Legislators promoting the changes note that industries that discharge toxic chemicals into the air would still have to meet federal standards. The state program, they argue, duplicates federal law and forces unnecessary expenses on industries in North Carolina. Some of the state’s largest industries and business organizations have been pushing legislators to abolish or greatly modify the state program.

State vs. Federal

But as the doctors pointed out in their letter the state air toxics rules are distinctly different than the technology-based federal programs. Federal air pollution standards focus on improving technology controls while state standards are based on protecting community health.

Supporter Spotlight

Federal rules, adopted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, establish technology controls on an industry-by-industry basis. Regulators determine the pollutants of concern from a given industry. They then decide the most effective air pollution technology to reduce the emissions. The regulations require industries to install pollution controls to achieve an established reduction in air pollutants.

Once the federal pollution controls standards are in place for an industry sector, the federal Clean Air Act requires the EPA to review the effectiveness of the standards every eight years and to conduct residual risk of toxic air emissions posed by an industry. But EPA is woefully behind in doing the residual risk analysis, state air officials say.

And federal standards do not necessarily cover all sources of emissions from a plant. Federal rules do not require, as the state program does, computer analysis of emissions of an air pollutant and concentration levels at a manufacturer’s property line.

For example, with pulp and paper mills, the federal air pollution rules do not cover 11 compounds such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan. The state does because they are considered a local health threat.

The state air toxics rules also require a facility-wide evaluation and estimation of the concentration of pollutants at the property boundary.

Typically, a plant expansion or addition of new production line will trigger a state requirement that a company do computer modeling to show the emissions will not be harmful to the surrounding community. Some plants must re-analyze their emissions several times within a year if they are constantly adding new production lines that increase emissions, state air officials said. If the analysis shows a plant is exceeding the fence-line concentrations for a given pollutant, the company has to change the design of the plant or eliminate the use of a toxic chemical used in a production process.

“We are often asked to quantify the specific benefits of the air toxics program,” said Mike Abraczinskas, deputy director of the N.C. Division of Air Quality, who acknowledged that it’s difficult to list. “By the time we get an application, they usually have figured it out.”

State Air Quality officials say the state and federal air regulatory programs are complimentary rather than redundant. The state applies standards that weigh health risks to the community, based on scientific studies of a particular chemical.

“It fills a gap where the federal program leaves off,” Abraczinskas said. ‘We have the authority in existing rules that allows us to address unacceptable risks from air toxics.”

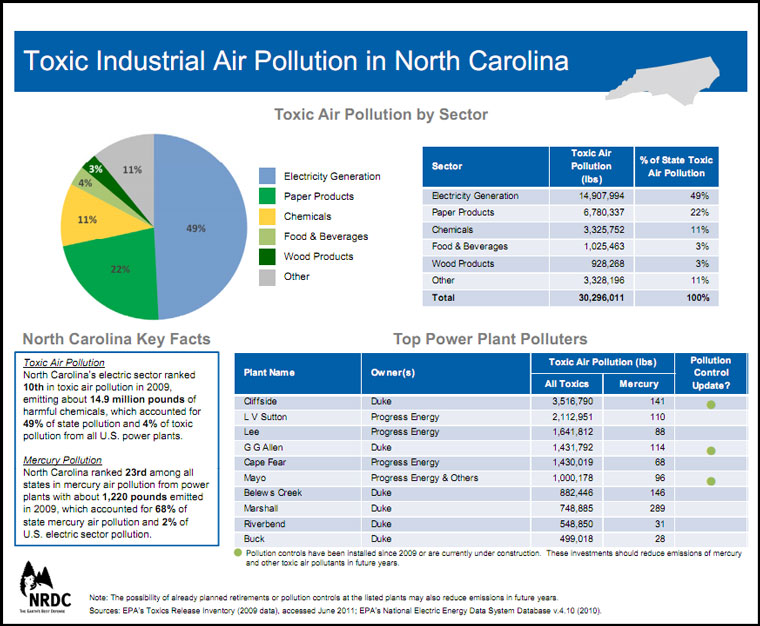

As a result of federal and state air regulations, toxic air emissions in North Carolina have steadily declined from more than 120 million pounds a year in 2000 to less than 40 million pounds in 2010, according to EPA data. Electric utilities remain the biggest contributors of air emissions in North Carolina, contributing 40 percent of pollution. Paper mills, such as the Domtar paper mill in Plymouth, contribute 22 percent and chemical manufacturers 13 percent. They are among the industries that are advocating scaling back the state air toxics program.

Born Out of Crisis

North Carolina’s air toxics program had its roots in the environmental concerns of the late 1980s. At the time, many residents of North Carolina were increasingly alarmed about the harmful effects of air pollutants on health. Two projects were feeding their concerns.

ThermalKEM was trying to find a county in North Carolina to accept a large commercial hazardous waste incinerator to dispose of waste from southeastern states. The siting process generated a lot of public anxiety.

Meanwhile, a commercial incinerator in Caldwell County burning waste paints and lacquers from furniture manufacturers was generating one worrisome headline after another. Federal health investigators declared that the Caldwell Systems’ activities posed a public health hazard to workers and the incinerator created a potential health threat to area residents.

Amid these growing public concerns, there was no effective state or federal program regulating toxic air pollutants.

Women in Northampton County in 1991 protest the proposed ThermalKem incinerator. Photo: N.C. Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. |

“We had very limited regulatory tools to deal with an emitter like that,” said Tom Mather, the public information officer for the state Air Quality Division. “EPA had been very slow to develop an air toxics program.”

Gov. Jim Martin and the N.C. General Assembly directed the state Department of Environmental and Natural Resources to develop an air toxics program. The rules adopted in 1990 initially focused on 84 pollutants with an additional 21 pollutants added the following year.

A number of states adopted air toxics programs during this period because the Environmental Protection Agency was behind schedule in adopting federal air toxics rules.

Today, the North Carolina Air Toxic Programs focuses on 97 toxic air pollutants. That includes 21 pollutants that are not covered by the federal air toxics program, including mercury vapors; hydrogen sulfide, a rotten-egg smelling toxic gas that is produced by paper mills and waste ponds; ammonia; and methyl mercaptan, a foul smelling gas produced by pulp mills.

The air toxic rules are developed by a panel of health scientists and toxicologists who study scientific studies about particular chemicals or compounds, then recommend concentrations limits that are safe for people living near the factories.

‘Director Calls’

An important provision of the state air toxics regulations allows the director of the Division of Air Quality to require that a manufacturer, utility or other source of toxic emissions submit computer estimates showing the concentrations of toxic air pollutants at the property are safe.

State air quality regulators issued a series of these “director calls” from 2007 to 2009 after reviewing toxic emissions generated by industrial boilers at 590 facilities statewide. The state’s analysis showed that the industrial boilers at 18 facilities were exceeding state standards for certain toxic pollutants. The air quality director issued directives to the boiler operators requiring them to modify their facilities to comply. Most were able to show compliance by accepting production limits or changing the fuels they were using.

Under the proposed changes to the air toxic rules, the division director would still have the power to issue a director’s call. But if the agency exercises that authority and requires a facility to submit air permit application and make modifications to comply, the division must inform the chairs of the legislature’s Environmental Review Commission of the circumstances surrounding the directive and provide a copy of the written finding.

Weakening of the state’s air toxics program would disproportionately affect Eastern North Carolina because of the presence of a number of the state’s largest producers of air toxics.

Ironically, exempting many types of industries from state air toxics standards also could make it more difficult for prospective industries wishing to locate in a community. A state air permit states that emissions levels are safe to the community beyond the property line.

“That’s an assurance an industry can provide the public,” said Mather. “Without an air toxics program, they are not going to have that to fall back on.”