First of two parts

NAGS HEAD — On a mild December morning, Marc Basnight stood on the shore of his family restaurant, the Lone Cedar Café in Nags Head, showing off the post-hurricane improvements. “Look,” he said, pointing to the newly placed riprap, “recycled concrete, crushed into small pieces. It cost me a fortune.”

Supporter Spotlight

He pointed to the edge, where the rock met the lapping waves of Roanoke Sound.

“But late at night I have counted thousands of mullet down there,” he said “And we will have zero stormwater coming off this property.”

Basnight, 64, has avoided the press since his retirement from the N.C. Senate a year ago. He has been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. In this country, it’s better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Still straight-backed, dapper and very sharp, he stays out of the public spotlight, in part because of a slowness of speech and weakness that makes it difficult for him to stand for long periods.

“I must have turned down 15 interviews, maybe more,” he said, shaking his head to yet another request.

Still, he couldn’t help giving a tour of the hardy roses that had survived a foot of water from Hurricane Irene. He proudly pointed out the restaurant’s water recycling system. He paused next to the back fences, fashioned from recycled cooking oil jugs and plastic drink bottles. A fence on the west side of the property consisted of carefully stacked wine and beer bottles.

Supporter Spotlight

“You should see that when the sun gets low,” he said, pointing to the glass assortment.

As pretty as the northern lights? A big grin spread across the senator’s thin face. “Yes. Beautiful.”

And a few minutes later, “Do you have time to ride to Jennette’s Pier?”

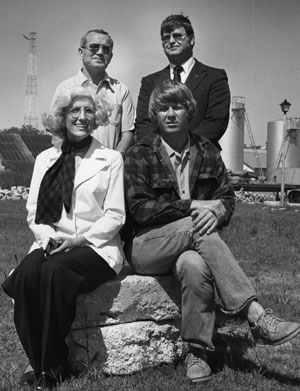

Marc Basnight (seated, right) joins the other members of the Dare County Bicentennial Committee in 1976. Seated next to Basnight is Natalie Case Austin. Standing are Bobby Owens, a county commissionor (left) and Carlisle Davis, the Manteo mayor. Photo courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center.

The Survivor

During his 26 years in the state senate—the last 17 as president pro tempore—Basnight grew to be the most politically powerful man in the state. He outlasted governors, opponents and many of his closest colleagues. He developed a reputation for ferociousness when it came to defending favorite causes—a number of which included protections for coastal waters.

He also grew beloved by his constituents, who knew him not only as the go-to man for solving problems, but as folksy and approachable, with disarming candor and charm. Basnight loved to chat with residents of District 1 whenever he stopped in a store or strolled the winter beach.

“I never wanted to be a leader,” he mused.

Really?

“Never. I didn’t want to be put on a pedestal. I wanted to challenge people and get them thinking big, beyond the problems in their own districts, about problems in the world.”

It’s been an interesting ride for a small-town native and graduate of Manteo High School—his highest educational honor until the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill awarded him an honorary doctorate of law in 1999.

As a legislator, Basnight was known for his curiosity and thirst to learn about issues. Discussing problems with constituents, he would turn to a staff member and say, “We need to know more about this. Get me a report about it.”

That wasn’t always the case. As a boy Basnight was a middling student who loved to have fun and play jokes on others. One classmate remembered Basnight piloting a skiff through flooded Manteo streets during Hurricane Donna, scooping up baby dolls that had floated out of the Ben Franklin store. There are also tales about an 11-year-old Marc organizing a town football team, with Saturday practices and occasional games against the rival Wanchese team.

In high school he played on the football team and hung out with pals, including Charlie Fearing and the late Buddy Davis. After graduating in l966, Basnight worked for the family construction business. Bobby Owens, Basnight’s brother-in-law and the long-time chairman of the Dare County Board of Commissioners, remembers a shirtless Basnight riding a bulldozer with his father. “He came from a large family and always worked hard,” Owens said. In 1968, Basnight married a local girl, Sandy Tillett.

‘Backwards Dumb’

His interest in civic affairs led him to a post as the first chairman of the county tourism board. He soon attracted the attention of the late Walter Royal Davis, an oil tycoon and a major influence in state Democratic politics.

“Mr. Davis took a liking to him and in a sense Marc became the son Mr. Davis never had,” Owens said. “At the beginning Mr. Davis told him how backwards dumb he was.”

Davis started sending Basnight the magazine The Economist and suggested other reading material.

Walter Davis

When he announced that he wouldn’t seek re-election in 1984, state Sen. Melvin Daniels asked everyone to support his cousin, Marc Basnight, who was then on the state Board of Transportation. “It was a total surprise to Marc,” Owens said.

In such a strongly Democratic county, it was tantamount to Daniels anointing his heir. Basnight won the seat handily.

Why did he enter politics?

“Isolation,” Basnight answered immediately. “I wanted to change that for the Outer Banks.”

When the legislative term opened in 1985, he attended a Democratic Caucus meeting in Pinehurst, where freshmen senators were invited to introduce themselves and say a few words. “I told them I’m from the Outer Banks, which you may not know about,” Basnight remembered. “Our roads were terrible, and our bridges. The highway to Hatteras was atrocious. I told them I felt like we should be part of the Commonwealth of Virginia. And I did feel that way.”

A wry smile creased his face.

“But I paid the price. I didn’t get very much accomplished that whole first year.”

It was a lesson he took to heart. Basnight was elected by business supporters, and everyone assumed it was to them he would pay his highest allegiance. But within a few years he developed an unusual interest in environmental issues. Bill Holman, then the only environmental lobbyist working the N.C. Assembly, remembers trying to get Basnight to support a ban against phosphate laundry detergents in 1985. Basnight didn’t go for it. “He was still very much in the mold of a DOT-construction guy,” said Holman, now director of state policy for the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University.

Interest in Environment

But a shift occurred after a group called the Friends of Hatteras Island began fighting development of a golf course in Buxton Woods on Hatteras Island, Holman said. The group feared that chemical fertilizers and herbicides from the course would pollute public drinking wells. Other residents complained of seeing pollution for the first time in local waterways.

“He talked to his constituents and found out how important clean water is to the economy,” Holman said.

Sen. Marc Basnight, left, has a laugh with Ken Mann, the past president of the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce, during a legislative breakfast in Nags Head in 1989. Photo courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center.

Basnight’s first years in the Senate coincided with a legislative sea change. The old guard was retiring, and the new senators had environmental issues on their radar screen.

“They were more moderate,” remembered Tony Rand, a long-time Democratic state senator and the majority leader from 2001 to 2009. “They came of age when the environment was something to pay attention to.”

“Some people come to the legislature and have a world view and they never change,” Holman said. “Marc started reading stuff and was intellectually curious enough to pay attention.”

Basnight specialized in helping those he came to call “the little man,” people without wealth or political connections whose needs, he believed, had long been ignored in Raleigh. To make it easier for working folks, he had his staff open his office early, by 7:30 or 8 a.m. and keep it open at least until 6 p.m. There was no voice mail or email in those days; every caller spoke with an aide. His style of constituent services was reminiscent of Jesse Helms, the Republican U.S. senator known for helping N.C. residents cut through government red tape. If you called Basnight’s office, you knew you would get a response—although Basnight would tell you frankly when he disagreed with you.

But Basnight took constituent services to a new level, Holman said. “Helms would solve problems, but he wouldn’t do anything about the policy that had caused the problems. Senator Basnight would want to fix the policy that had caused it. He wanted to change things. He worked his ass off. He was incredibly driven.”

Basnight never lost his Outer Banks hoi-toide accent, and the Raleigh press made much of his frequent malapropisms. Nonetheless, he quickly learned to maneuver through the Capitol. “He was comfortable in his skin,” Rand said.

He became known as a forceful orator and political player.

Then in 1988 a Republican, James Garner, defeated Tony Rand in his bid for lieutenant governor. The election of a Republican to that office set the stage for a procedural change that a few years later would greatly affect the senator from District 1—consolidating his power and thrusting him into the crosshairs of controversy.

Tuesday: Marc Basnight’s rise to power