First of two parts in a series special to Coastal Review

To many Carolinians coming to the beach for a little fishing, the mullet is a lowly baitfish, often cut into strips for bottom fishing. They may confuse it with an unrelated fish in the drum family known locally as the “sea mullet.”

Supporter Spotlight

To the folks of Down East Carteret County, and some locals throughout coastal NC, however, the “jumpin’ mullet,” as they call it, owns a special place in their hearts and kitchens. Often known as the grey mullet, flathead mullet, or striped mullet elsewhere in the English-speaking world, Mugil cephalus is a consummate jumper.

Back in 1980, while cutting mullet strips to use on offshore trips on the Carolina Princess with the original owner and captain, the late James “Woo-woo” Harker of Harkers Island, he and I would joke about how much better-flavored they were than the fish that we caught with them to sell at the fish house or that our clients from upstate were seeking on their charter trips with us — red snappers and groupers mostly. (Those were different times!)

For nearly a decade by then, I had been learning from my in-laws, the Pigotts and Nelsons of Carteret County: 1) how to strike-net mullet in a fast shallow-draft boat with lots of gill-net set in a circle around a seething school of mullet; 2) how to charcoal the fillets on pecan wood, for several hundred people at a time if necessary; and 3) how to prepare that most wonderful of eastern North Carolina delicacies – dried mullet roe – the bottarga di muggine of Italian cuisine (more on that later).

Well over a century ago, many Carteret County families literally cast their fates with the mullet fishery. Some of my wife Lida’s relatives even followed the mullet fishery elsewhere, particularly to Cortez and Punta Gorda, Florida, as described by historians Dr. Mary Fulford Green and David Cecelski.

This “mullet fishermen’s migration” showed how important one species of fish can be to human livelihoods and culture, reminiscent of the singular role of cod in European history or salmon for the Northwest Coast Native American tribes and the indigenous Ainu of northern Japan.

Supporter Spotlight

But where did North Carolinians pick up mullet fishing and all that goes with it, especially their appetite for the dried egg masses? North Carolina explorer John Lawson wrote in 1709 that eastern parts of the state had “Mullets, the same as in England, and in great Plenty in all places where the water is salt or brackish.”

Perhaps Down Easters may have learned originally about mullet and their fabulous roe from their Native American neighbors in the late 1600s and early 1700s, who undoubtedly knew it well.

Or perhaps, one could speculate, they learned or relearned directly from cultural transmission from Europe. After all, fishermen in this area have been selling mullet roe for export to Italy for many decades. In any case, drying mullet roe for cooking later is part of the “traditional ecological knowledge“ (TEK of anthropological lingo), of eastern Carteret County people.

During World War II, my father-in-law, the late Osborne G. “Bill” Pigott, asked his family back home to send him just one thing – some dried mullet roe. When he heated it on the wood stove in his tent somewhere in France, it drove his tentmates out with its powerful smell. “That was OK,” Bill would recount with a twinkle “more for me that way.”

As Lida and I made our way through the 70s and a subsequent half-century, we crossed paths with the cosmopolitan, under-rated mullet in many improbable places. It’s truly a worldwide fish and fishery, we began to realize, as we encountered them in fish markets of Europe, Africa, Madagascar, Hawaii, and elsewhere.

Part of our research involved excavating fossil sites on islands, to try to better understand past natural and human roles in the drastic environmental changes there. Lida and I feel really lucky to have done island paleoecology all around the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans.

Several of our sites on the Hawaiian island of Kaua`i, especially Makauwahi Cave on the south shore, were full of bones of prehistoric mullet, that same Mugil cephalus as our “jumpin’ mullet.”

Sites we excavated and radiocarbon dated showed mullet were there in large numbers thousands of years before the first humans to land on those shores. But we also studied prehistorically managed fishponds, places where the mullet (`ama`ama in Hawaiian) were raised in large numbers.

Oral tradition indicates that mullet were caught in nearby estuaries and transferred live to these ponds, or lured inside through slatted gates. They were kept well-fed on what mullet like best, low-on-the-food-chain treats like algae and zooplankton. These most revered fish were for consumption only by the ali`i or chiefly class. Commoners could make do with ordinary reef fish and such, but for the chief and his guests – it was likely to be `ama`ama.

On outings with my friend Joe Kanahele of Ni`ihau Island, I had the good fortune on several occasions to see how native Hawaiians catch mullet and similar fish today. With an oversized cast net, he would often catch a dozen large fish in one throw, after a careful stalk along a rocky shore.

On the Alakoko (Menehune) Fishpond near Lihu`e, I helped the pondkeeper, Robert Rego, set a gill net across the pond, and we caught and ate some nice mullet — from the same place Hawaiian aquaculturists practiced mullet farming in a pond that our radiocarbon dating had shown they built in the 1300s.

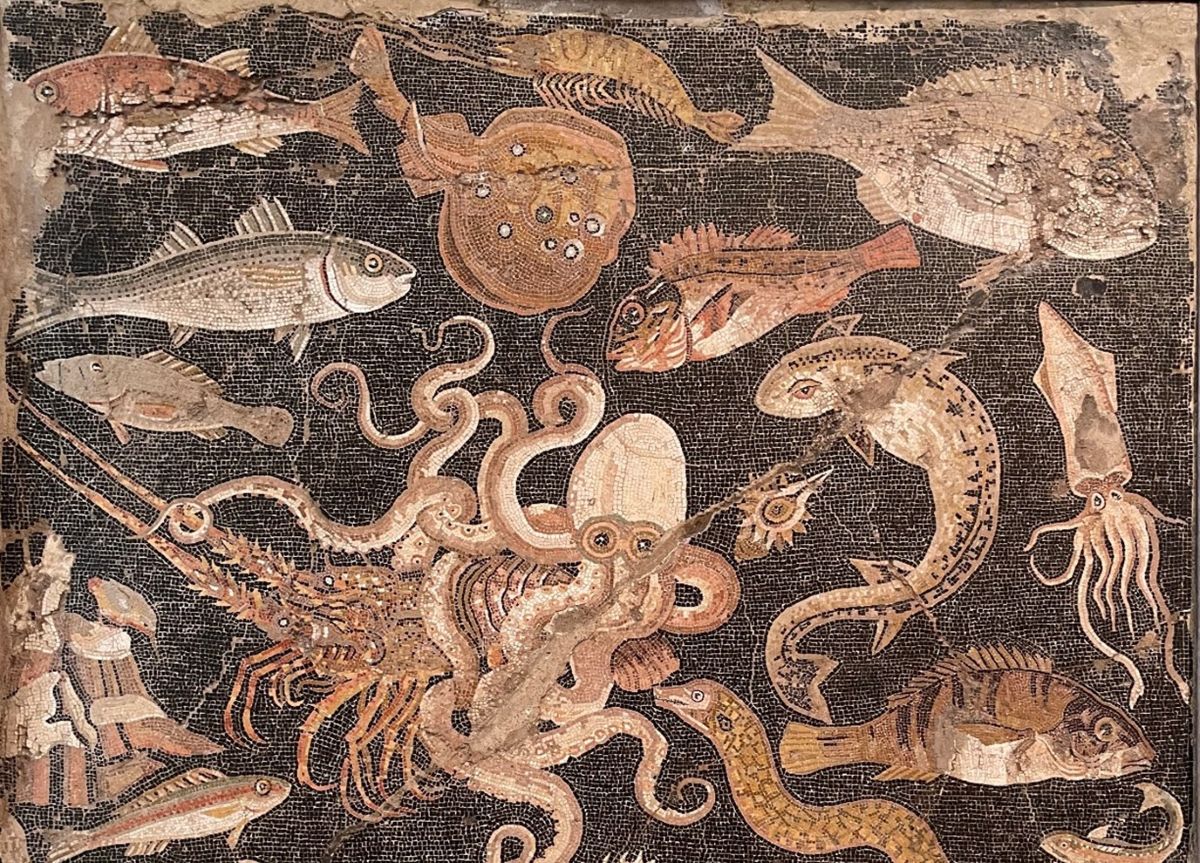

Native Hawaiians were among the first people to build fishponds and cultivate fish on a large scale, but they were certainly not the only ancient folks, as Pliny the Elder writes about Roman fishponds shortly before his demise in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the volcano that buried the Pompeii area in 79 C.E.

The magnificent tile mosaics and other art recovered from the buried city included pictures of — you guessed it — mullet. Two kinds actually, our grey, or jumpin’ mullet (cephalo in Italian), and the red mullet (Mullus surmuletus, or triglia di scoglio in Italian).

So the ancient Romans knew all about our dear Carteret County fish, but although Rome might have been the capital of the known world at that time, the real capital of the jumpin’ mullet is arguably the Mediterranean island of Sardinia.

In part 2, Lida and I will make a “culinary pilgrimage” to the very heart of the mullet fishing and bottarga-making industries, along a body of water so much like our own Core Sound. Our cosmopolitan fish was already at the center of the culture there before the time of Stonehenge and the pyramids.

Next in the series: Back to where it all began