Part of a series about the effects federal budget and staff cuts and the cancellations of programs and services are having in coastal North Carolina.

The call from the North Carolina Attorney General’s office late last year relayed news of a victory.

Supporter Spotlight

A federal judge in Boston on Dec. 11, 2025, sided with Jeff Jackson and 19 other state attorneys general in their case against the Federal Emergency Management Agency, informed the caller.

U.S. District Court Judge Richard G. Stearns ruled that FEMA unlawfully terminated a federal grant program under which roughly $200 million had been awarded to North Carolina communities, including Pollocksville, to tailor projects to reduce and prevent storm damage.

Stearns issued an immediate, permanent injunction restoring the Building Resilient Infrastructures and Communities, or BRIC, program.

“And, that’s all we’ve heard,” Pollocksville Mayor Jay Bender said. “We’ve never heard anything official from FEMA saying yay or nay. We have not heard anything from North Carolina Emergency Management saying yay or nay.”

FEMA funnels BRIC grants to state emergency management offices, which are responsible for managing and passing funds on to grant recipients.

Supporter Spotlight

N.C. Division of Emergency Management’s Justin Graney, chief of external affairs and communications, said in an email that the agency had not been notified by FEMA as to when funding would be released.

“NCEM continues to work closely with FEMA to determine the next steps and looks forward to a resolution,” Graney said.

But any such resolution could be, at a minimum, months away.

The federal government still has time to appeal Stearns’ decision. The 60-day window to challenge his ruling closes before the middle of next month.

The N.C. Department of Justice’s communications office confirmed in an Jan. 26 email that FEMA had, at that time, not filed an appeal in the case.

“We are closely monitoring FEMA’s compliance with the court order,” the email states.

FEMA’s news desk at its regional office in Atlanta did not respond to requests for comment.

The agency announced without any forewarning last April it was canceling the BRIC program, one created under President Donald Trump’s first term in office.

But just three months or so into Trump’s second term, an unnamed FEMA spokesperson stated in the announcement that the agency considered BRIC to be “wasteful” and “political.”

FEMA later clarified only projects that had been completed would be fully funded, erasing congressionally appropriated funding for more than 60 infrastructure projects in North Carolina.

Jackson joined a lawsuit filed last July by a coalition of state attorneys general who argued FEMA’s termination of the program was unlawful.

The court agreed, concluding that FEMA did not have the authority to end BRIC because Congress, not the federal agency, appropriated funds for that program.

“The BRIC program is designed to protect against natural disasters and save lives,” Stearns wrote.

“Our towns spent years doing everything FEMA asked them to do to qualify for this funding, and they were in the middle of building real protections against storms when FEMA suddenly broke its word,” Jackson said in a release following the court ruling. “Keeping water systems working and keeping homes out of floodwater isn’t politics – it’s basic safety.”

Pollocksville and Leland were selected to each receive about $1.1 million through the BRIC program.

Leland plans to relocate the town’s sewer system away from Sturgeon Creek from which floodwaters rise often after storms and natural disasters.

Jessica Jewell, Leland’s communications manager, said in an email that the town is exploring other grant opportunities to help fund their project.

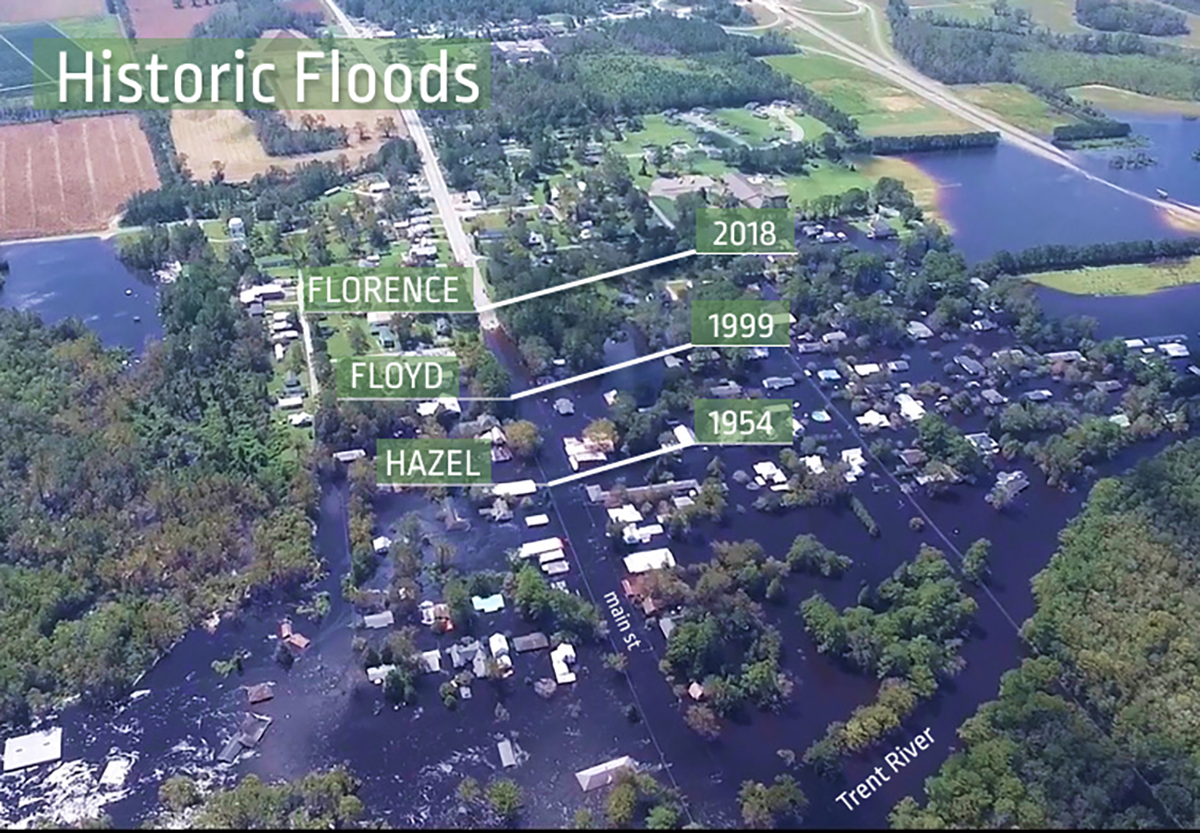

At the time of FEMA’s announcement last April, Pollocksville had already paid out about $18,000 in legal, advertising and procurement fees ahead of the project the Jones County town had secured to raise six commercial buildings in its downtown next to the Trent River.

“I mean, this is a project that we thought was done,” Bender said. “We had a contractor. That was probably one of the most frustrating things. We were already under contract.”

Before the state attorneys general filed their lawsuit, town officials were contacted by the state and encouraged to submit their project proposal through the Hazard Mitigation Grant program. The HMGP is federally funded, but managed by the state Division of Emergency Management.

“Having to file all the same paperwork over – I don’t know that I can convey to you the complexity of the paperwork,” Bender said. “The positive thing about this, going through HMGP as opposed to going through FEMA, is that HMGP will be at no cost to the town. There’s no match and so that will obviously make it a more financially attractive proposal than FEMA.”

He went on to say that the town will take “the best deal that comes the quickest.”

“I will feel much more confident when there is an actual piece of paper to sign and when I see people on the street preparing elevate a building,” he said.