BUXTON – Faced with devastating destruction across a significant segment of its beachfront, this small Outer Banks village is seeking help for coastal solutions, including measures that could require potentially controversial legislative action by the state and federal governments.

Since September, 15 houses have collapsed on a stretch of beach in Buxton just north of Cape Hatteras, the distinctive point of land midway along the East Coast that juts far into the Atlantic. Adaptation to storms and natural forces have fortified the community since its establishment in the late 1800s, but now stunningly rapid erosion is endangering its future.

Supporter Spotlight

“Today, small areas of our oceanfront have deteriorated to the point where we can no longer shoulder these challenges alone,” Dare County Board of Commissioners Chairman Bob Woodard wrote to members of the North Carolina General Assembly in November. “With your support, we can preserve our coastline, protect public infrastructure, and sustain the economic engine that benefits all of North Carolina.”

The county is one of the few “donor counties” in North Carolina, with more than 3 million people annually visiting Dare’s beaches and national parks and generating significant state tax revenue, he said. So far, he added, the county has spent about $275 million for beach nourishment as well as additional millions to maintain inlets, with little state or federal assistance.

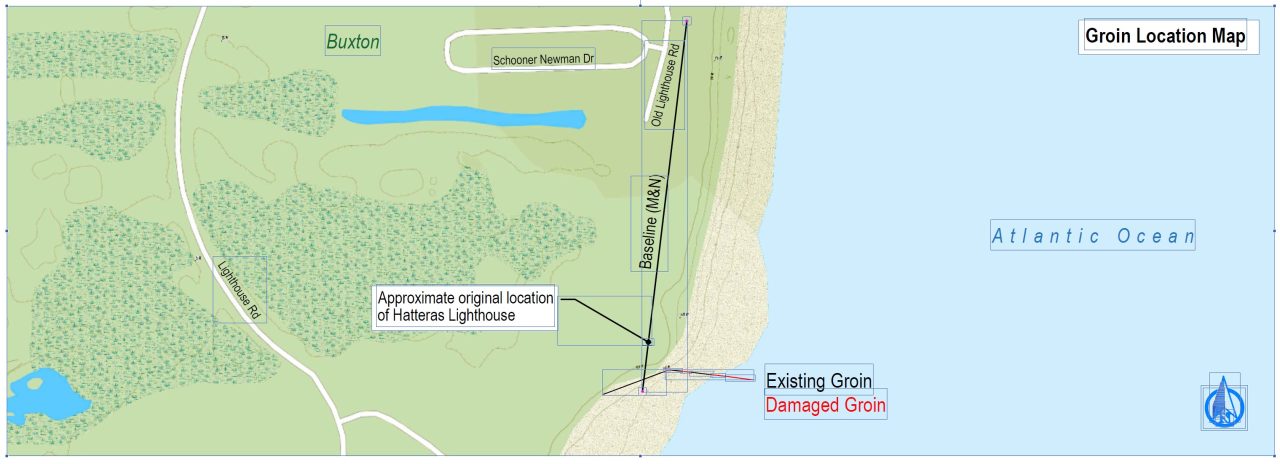

In addition to a beach nourishment project in 2026 for Buxton, the county is planning to repair a purportedly half-intact groin, one of three installed in 1969 to protect the former Navy base constructed in 1956 near the original location of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

Dare and Hyde counties also have asked the state Division of Coastal Management to lift the 1985 state ban against hardened structures so the remnants of the two deteriorated groins at the site can be replaced.

But beach stabilization of any sort on the Outer Banks, with its extraordinarily high-energy coastal conditions, is becoming more challenging in a changing climate with quickly evolving and often unpredictable consequences: Sea levels are increasing faster than projected, storms are intensifying, rainfall is heavier.

Supporter Spotlight

In recent years, Hatteras and Ocracoke islands on the barrier islands’ southern end have been suffering dramatically increased shoaling in its inlets and far worse erosion at numerous hot spots along N.C. 12, the island’s only highway. Over wash, loss of dunes and road damage is becoming more frequent and difficult to mitigate, sometimes resulting in loss of vehicular access for hours or days.

People say things feel different. Residents — from old timers to long-time transplants — have noticed places flooding where they never did before, shoaling in waterways that had never clogged before, and erosion consuming an entire shoreline that had been wide and stable just a few years before. And this fall and winter, even seasonal nor’easters have switched to overdrive, with the storms coming in one after another and more often than some ole salts say they’ve ever seen.

“When we really developed these islands in the ’70s and ’80s, it was a different system, and we need to recognize that, acknowledge it, and plan accordingly,” Reide Corbett, executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute and Dean of the Integrated Coastal Program at East Carolina University, said in a recent interview. “We can’t let self-interest lead the way. We need to understand what this looks like, and we need to get behind better policy. And it starts with how we develop.”

Responding to increasing numbers of house collapses in Buxton and Rodanthe, the Hatteras Island’s northernmost village, state leaders are urging Congress to pass legislation introduced by Rep. Greg Murphy, a Republican from North Carolina’s 3rd District, that would authorize proactive Federal Emergency Management Agency flood insurance payments to remove threatened oceanfront houses before they fall.

While the proposal has garnered bipartisan support, FEMA is currently understaffed and targeted for downsizing, reorganization or even elimination, and its flood insurance program is woefully underfunded.

A delegation representing local, state and federal officials toured the damaged area in Buxton on Nov. 24, where dozens of additional oceanfront houses are scattered willy-nilly, awaiting near-certain demise. Numerous members of the group expressed shock at the disarray and destruction at the scene.

Meanwhile, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Reid Wilson has directed the Coastal Resources Commission’s Science Panel to analyze shoreline stabilization options, including the potential effectiveness or negative impacts of groins.

Erosion on Buxton’s oceanfront has been a persistent problem for many decades, at least to the infrastructure on the beach, such as the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

“It was quite obvious to everybody that in the course of time the lighthouse would topple into the Atlantic Ocean and the thousand acres of park land, upon which no tree and scarcely any blade of grass grew, would be swallowed up by the warring ocean currents that swirl around the point of Cape Hatteras,” author Ben Dixon MacNeill wrote in an article published on July 30, 1948, in the Coastland Times. At that point, he noted, in just the lifetime of a middle-aged man, erosion had already whittled away 1,500 feet of beach.

Despite the 1937 congressional directive to the National Park Service to preserve what would later become Cape Hatteras National Seashore as a “primitive wilderness,” until the early 1970s, according to park documents, the agency spent more than $20 million to stop the “natural process” of barrier island movement. Projects included installing in 1930 steel sheet pile groins along the beach by Cape Hatteras Lighthouse; installing in 1933 additional sheet pile groins at the lighthouse; nourishment of the beach in 1966 near the Buxton motel area with sand dredged from Pamlico Sound; and in 1967 placement of revetment of large nylon sandbags in front of the lighthouse.

In addition, the U.S. Navy built three reinforced concrete groins in 1969 to protect its facility near the lighthouse; the beach near the Buxton motels was nourished again in 1971 with material dredged from Cape Point; and the beach near the Navy operation was nourished in 1973 with Cape Point sand.

Those actions were in addition to construction and repeated reconstruction of sand dunes, as well as beach fences and planting grasses, shrubs and trees to hold the dunes.

Finally, in 1973, the National Park Service acknowledged the futility and unsustainable costs of stabilization, and abandoned its efforts. The agency, however, did continue various attempts to protect the lighthouse with riprap, offshore artificial grass, sandbags and a scour-mat apron. With the sea by then lapping at its base, the lighthouse in 1999 was relocated a half-mile inland.

In a letter dated Jan. 9, 1974, from the U.S. Department of Interior to a Buxton resident, the agency promised that all available data would be analyzed before determining future beach stabilization management decisions in the Seashore, including relative to the groins.

“The most reliable scientific data we have obtained thus far offer no evidence that the existing jetties or groins at Buxton provide acceptable protection from ocean forces,” the department added. “While some stabilizing effect may be gained in the immediate area, the jetties actually cause more erosion in adjacent locations.”

A report the year earlier published by University of Virginia coastal scientist Robert Dolan, et. al, to analyze the effects of beach nourishment in Buxton, in fact, said that the groins — short jetties extending from a shoreline — rapidly increased erosion by the motel area, causing dune destruction and ocean over wash into private property.

“The groins, somewhat unexpectedly, are trapping sediment at the expense of the beaches to either side and as a result of their success, the reach protected by the groins has become stable,” the report said, adding that the localized erosion problem at Buxton had followed construction of the groins.

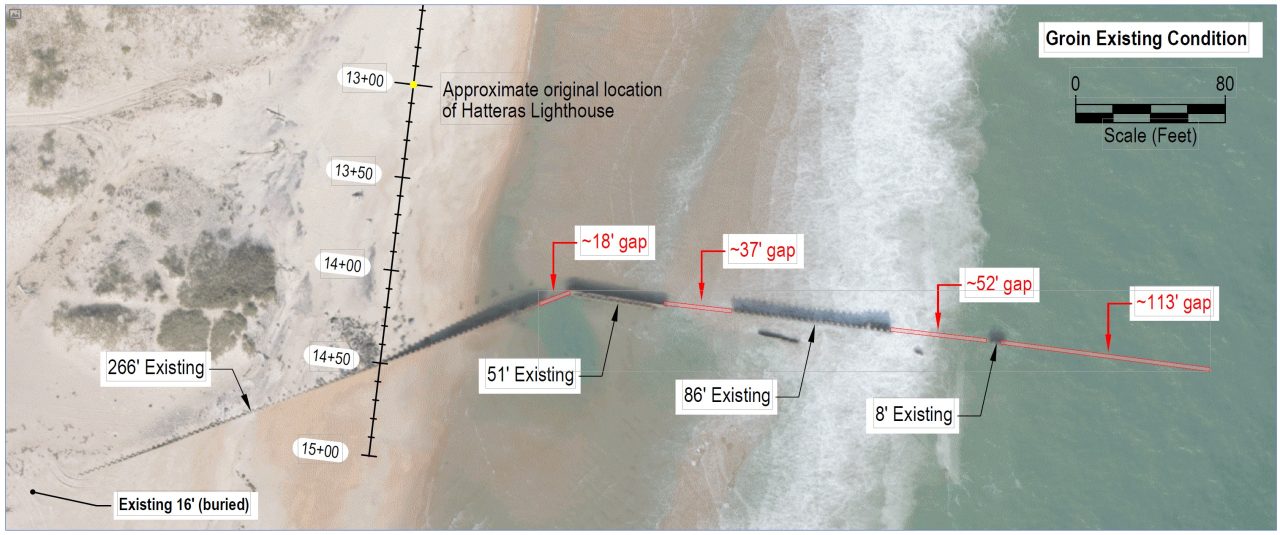

Barely more than four years after they were built, the groins were damaged by storms and required repairs with new sheet piling. Patches and reinforcements continued until the Navy in 1982 abandoned the base, apparently leaving the groins to the elements.

By the time heated discussions kicked in about whether the lighthouse should be saved in place or moved, the community tried to persuade the federal government to not only maintain the by-then-deteriorating existing groins, but also to add a fourth groin. The petition was soundly rejected, and the Navy, the Park Service and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers appeared to want nothing to do with the groins.

Today, the county sees the sand trapping barriers — even a single groin — as a way to prolong the effectiveness of a $50 million beach nourishment project, and importantly, as a way to buy time while consultants determine a long-term strategy for Buxton.

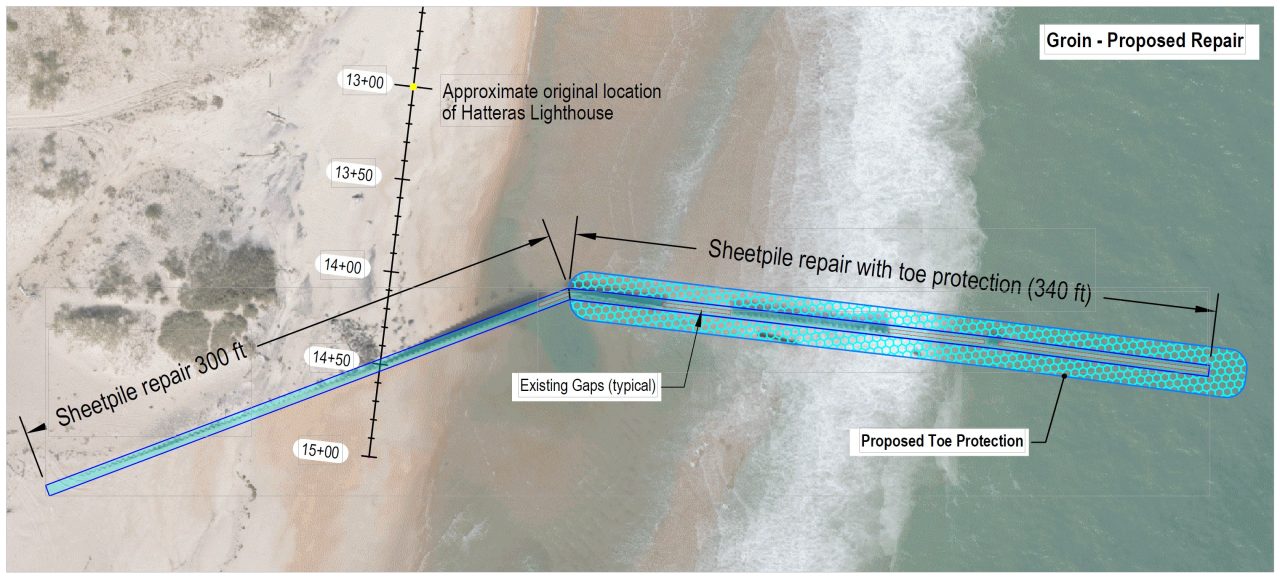

Dare County Manager Bobby Outten reported in March that, according to Coastal Science & Engineering, the firm hired to do the beach nourishment and groin work, the southern-most groin would meet the state’s 50% rule that allows repair of an existing structure that has 50% or less in damages. The county is currently awaiting approval from the state, as well as acknowledgement that the application meets the exemption criteria for an exemption from the hardened structures statute, he said.

If the groin work is approved, contractors estimate the $2 to $4 million project would take up to two months to complete this summer and involve about 640 feet of repairs, using steel sheet pile and riprap scour protection within the original footprint.

As Outten summed up the current dilemma facing Dare and other North Carolina coastal communities: There are two extremes, either hold the coast in place as it is, and build sea walls. Or let nature take its course, let the houses fall and see the economy crumble.

“And neither one of those extremes is acceptable,” he told Coastal Review. “To anybody.”