The blue crab population in the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine System is taking a hit sometime between when juveniles leave their nursery habitats and before reaching sexual maturity, a recent study finds.

Published last month in Fisheries Oceanography, “Long-Term Trends in Juvenile Blue Crab Recruitment Patterns in a Wind-Driven Estuary” examined the density of blue crabs in three different types of nursery habitats during the instar stage of the species’ complex life cycle. That’s when the tiny juvenile crab is about the size of a pea.

Supporter Spotlight

The North Carolina blue crab population began declining in the early 2000s, and despite state-mandated measures implemented in the years since to protect the lucrative fishery, the population hasn’t recovered. “With fishing accounting for approximately 80% of total annual blue crab mortality, these measures were expected to allow the stock numbers to recover, which has not occurred,” the study explains, referencing a 2018 N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries report. “This absence of recovery has often been attributed to recruitment overfishing.”

But, that’s not what the authors found.

The research shows that the juvenile blue crab population numbers from the late 1990s and the late 2010s are similar, and point to a “potential population bottleneck occurring in later life stages.” But the bottleneck is not the result of recruitment overfishing, which “occurs when the spawning stock of a population has been depleted to the extent that there are insufficient adults to produce the required number of recruits to replenish the population.”

Lead author of the study, Erin Voigt, is a doctoral candidate in David Eggleston’s lab in the North Carolina State University’s Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. Also listed as authors are Eggleston, a professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences, and previous N.C. State doctoral student Lisa Etherington.

Voigt told Coastal Review that one of the biggest takeaways from her research, at least in looking at the instar stage, is that “there is no evidence of recruitment overfishing.”

Supporter Spotlight

And if it’s not recruitment overfishing, “then that means that there’s something going on after the instar stage but before the adult stage that’s resulting in the blue crab population not rebounding,” Voigt said.

Another component of the study, which also relates to Etherington’s work, was to determine which habitats the blue crabs use.

Voigt sampled at Ruppia seagrass beds and shallow detrital habitats found along the mainland shores and the mixed species seagrass beds on the sound side of the Outer Banks.

Early in the life cycle, when the megalopae return to the inlets, the seagrass bed structure is the first nursery habitat they encounter on the sound side of the Outer Banks if there are no storms to interfere with the pattern.

“However, the surprising thing that we found was that if you look at the density of blue crabs,” which she said is the amount of blue crabs per meter squared, “you find almost four times as many blue crabs in these super patchy, very hard to see, kind of scruffy seagrass beds on the western shore.”

The researcher, the research

Originally from Maryland, Voigt earned her bachelor’s in biology from St Mary’s College, spent a few years researching at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, and then earned her master’s in ecology at San Diego State University.

She began her doctorate in 2016 but took an extended leave of absence when she began working in 2023 as program coordinator of the Duke University Marine Lab Scholars and Climate Scholars Program. Voigt resumed her research earlier this year and plans to defend her thesis later this semester.

Voigt began explaining her research by reviewing the “complex life cycle” of a blue crab.

In early summer, the male and female typically mate upriver in low-salinity environments. The female, or sponge crab, carries the eggs on her stomach. When it’s time to hatch, the planktonic larvae, or zoeae, which Voigt said look like space aliens, drift into the inlets or ocean and undergo several molts, with the last transition in the ocean being to the megalopa or megalopae phase.

“The megalopae have a little bit more swimming ability. They look less like aliens and slightly more like something that you might consider a crab or a shrimp,” Voigt said.

Starting in late summer and early fall, the winds shift from primarily southerly to northeasterly, and with that shift, the megalopae are pushed back into inlets, usually the Oregon and Hatteras inlets. They will use their sensory capabilities to find a nursery habitat and then transform to instar, or a small crab.

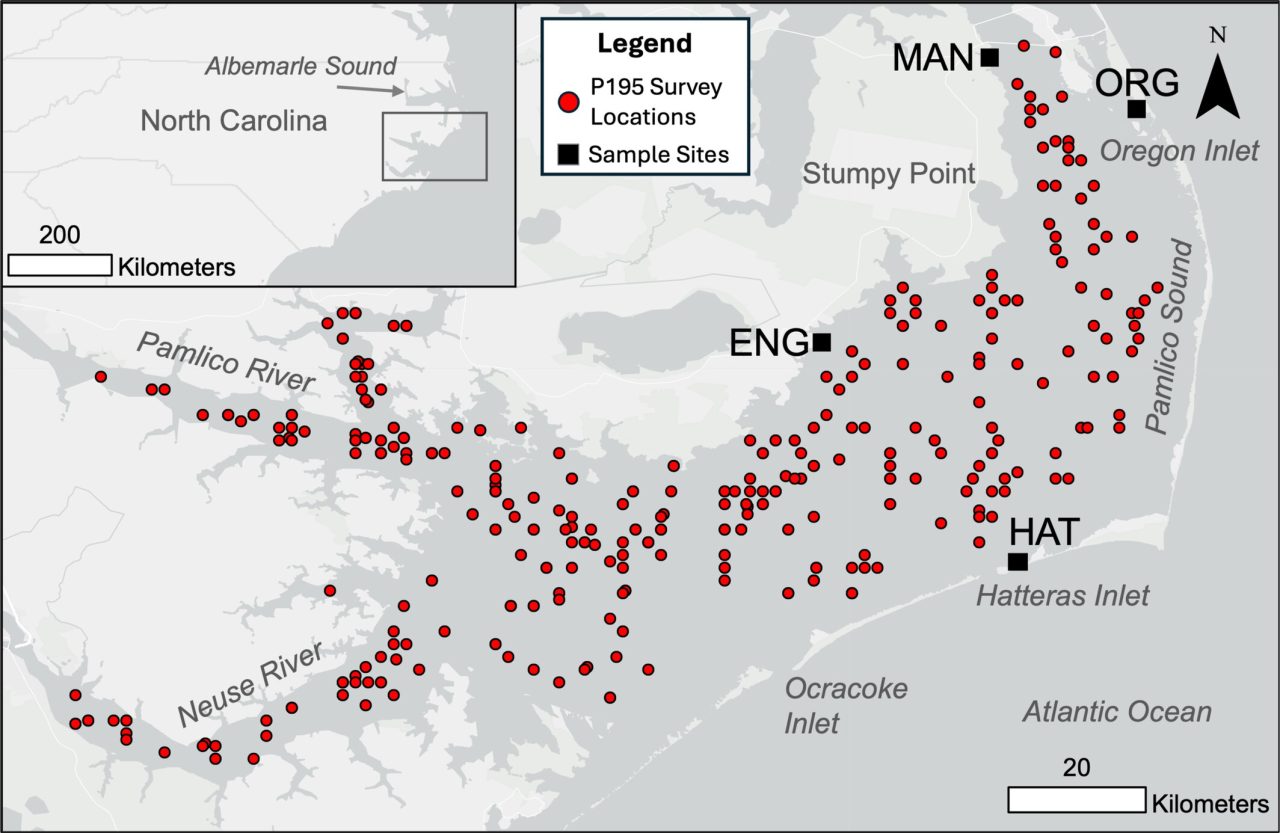

The instar stage in the life cycle is the focus of her study, she said, and builds on the research of previous graduate students in the Eggleston lab, including Etherington, who had sampled areas within the Pamlico Sound between 1996 and 1999 to learn where juvenile blue crabs were settling.

“In about 1999 — unrelated to her experiment — there was a massive overfishing event, and this occurred due to three hurricanes,” which were Floyd, Dennis and Irene. Overfishing means that a species is being removed at a rate too high for the population to maintain.

The inundation from these storms decreased the salinity upriver, forcing blue crabs to migrate to smaller, higher-salinity areas. This concentration led to a 300% increase in catch-per-unit effort, which is a way to measure how abundant a species is by dividing the total weight of the catch by total amount of work it took, such as hours fished and with what equipment.

“There was just a ton of blue crabs caught that year. We had a really high take. The blue crabs have never rebounded from that,” Voigt said. “There has been a decrease in fishing pressure during that time — a 50% decrease in fishing pressure — and we still have not seen it rebound.”

Then in 2016, when Voigt began as a doctoral student, Eggleston told her he found it interesting that the blue crab population wasn’t rebounding and it wasn’t clear why, though the going theory was recruitment overfishing.

For her research, she sampled from 2017 until 2019 the same exact locations Etherington had sampled 1996-99 for her study.

Voigt said she expected to find a strong reduction in the number of crabs in these key nursery habitats, “because if we’re running into recruitment overfishing, then you’re assuming that not enough juveniles are recruiting back into Albemarle-Pamlico Sound, and therefore you will not see as many instars in these habitats,” Voigt explained.

“However, what’s really interesting about this study was that we did not find that. In fact, the numbers of blue crabs we found when I studied were statistically no different from the number of blue crabs” that Etherington had found when she sampled the same areas before the fisheries collapse, Voigt continued.