Editor’s note: The following is from historian David Cecelski’s “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.” He introduced the nearly 20-part photo-essay series in early August, explaining at the time that the images he selected from the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Collection were taken between 1937 and 1951 of the state’s farms, industries, and working people.

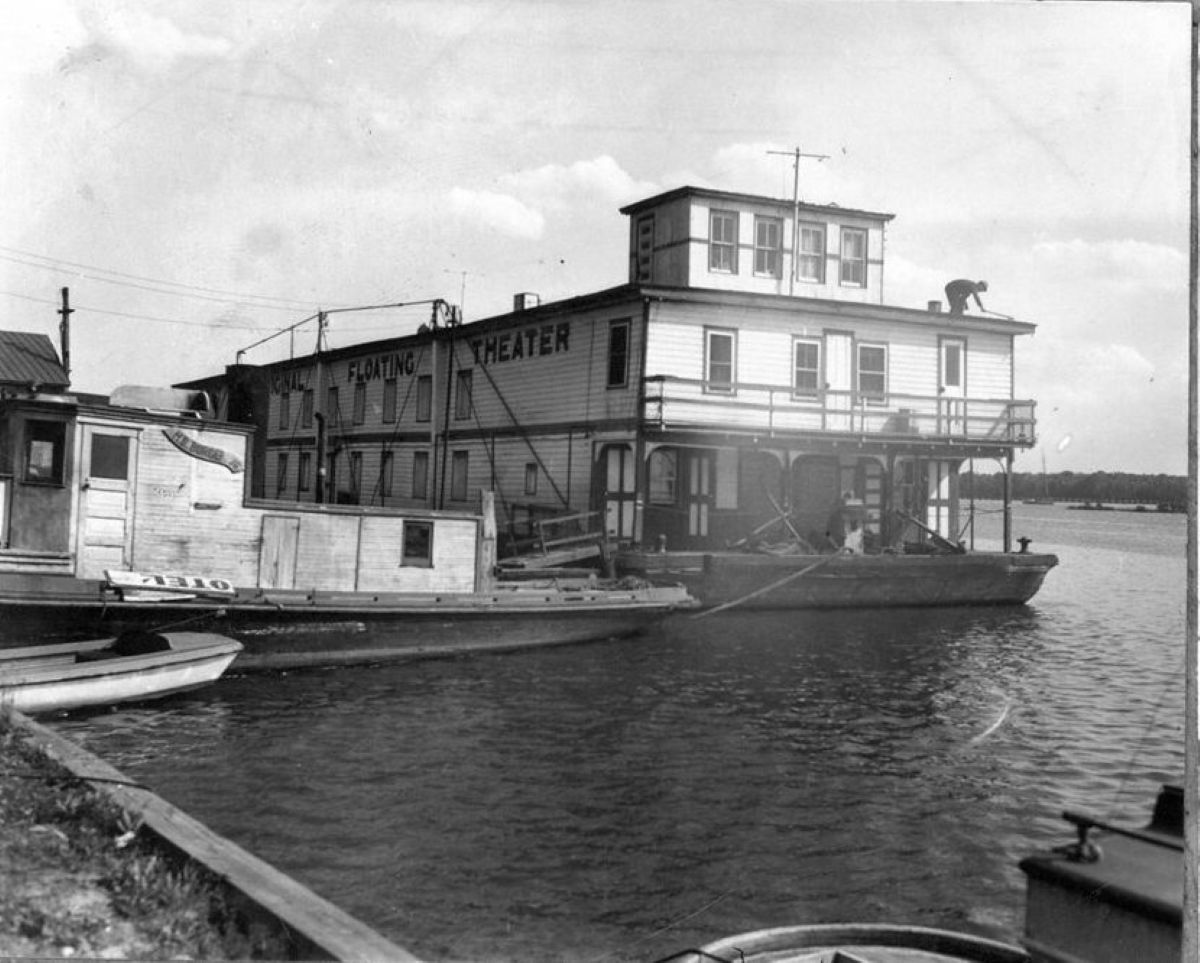

One of the more unusual scenes of working life that I found in the NCDC&D Collection at the State Archives in Raleigh was a series of photographs taken aboard the James Adams Floating Theatre while docked on the Pamlico River in Washington in 1940.

Supporter Spotlight

The James Adams Floating Theatre’s troupe of actors and actresses toured coastal waterways from Florida to New Jersey from 1914 to 1941. Tugboats towed the theater from town to town, and the boat’s troupe usually did a weeklong run before heading to their next stop.

Over the years, I have seen many photographs of the James Adams Floating Theatre. However, nearly all of them have been looking at the Floating Theatre and its traveling troupe of performers from a distance, usually when it was tied up at a wharf or being towed down a local waterway.

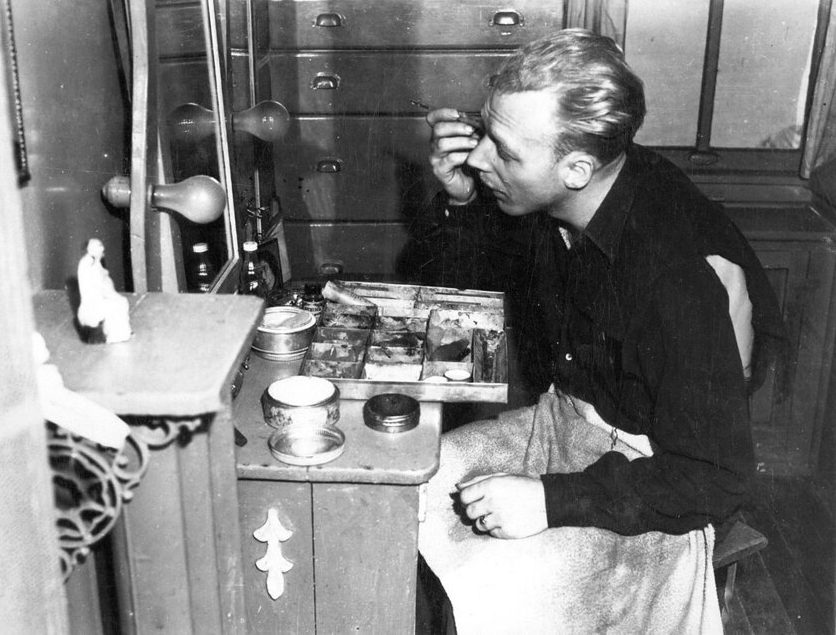

This group of photographs is different. Most were taken on the Floating Theatre, and they show the daily life of the boat’s performers and crew in a way that I have never seen before.

They show actors and actresses rehearsing a play. They take us into the boat’s galley and introduce us to the troupe’s cook. They give us a view into the ticket booth, and of one actress preparing her costume, another whiling away time between performances by fishing off the barge.

And, as we see in the photograph above, they give us a glimpse of stage manager and actor Daile Herlit doing his makeup just prior to a performance.

Supporter Spotlight

-3-

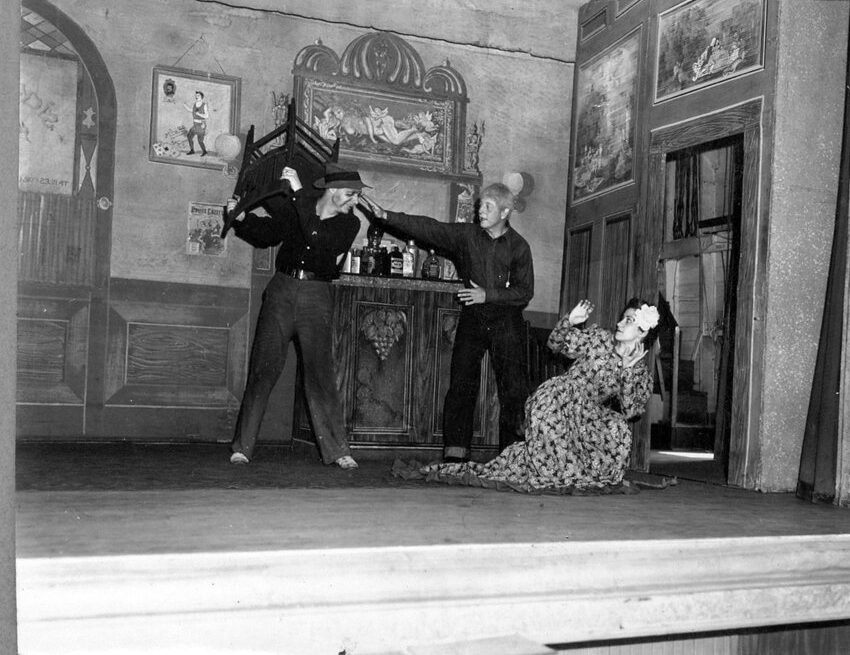

In this photograph, we see members of the boat’s troupe rehearsing a scene from a popular temperance play called “Ten Nights in a Bar Room and What I Saw There.”

Based on a very popular 1854 novel by Timothy Shay Arthur, the play had been a staple on Vaudeville and in traveling shows for many a year.

The actress in this scene, Helen Brown, was one of the troupe’s stars.

Reflecting on the Floating Theatre’s heyday, Earl Dean of the Durham Morning Herald Oct. 1, 1950, recalled that the troupe’s staple fare was “the old blood-and-thunder melodrama with an atmosphere supercharged with dark and dirty deeds, tear jerkers with a pretty maiden, a mortgaged homestead and a villainous sheriff with a mortgage in his hip pocket.”

Plays like “Ten Nights in a Bar Room” were really just part of the offerings on the Floating Theatre though.

Musical performances, magic acts, ventriloquism, acrobatics, fortune telling, maybe a magic lantern show or even a pet act or two — there was no telling what you might see when the curtain went up!

-4-

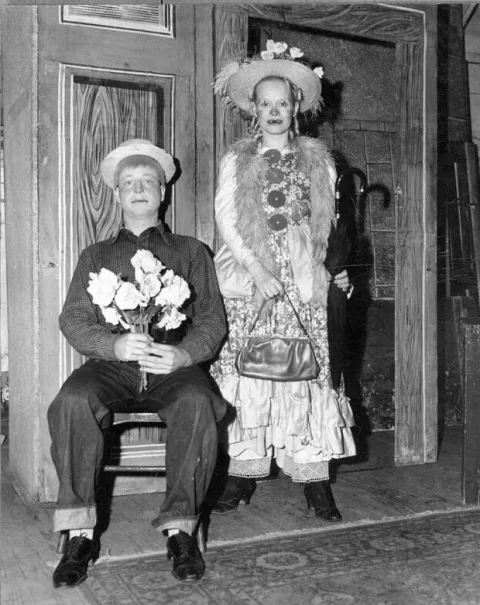

Here we see a winsome pair of clowns all dressed up and ready to go on stage.

In the reminiscence that he published in the Durham Morning Herald, Dean described the Floating Theatre as “a great seagoing barn on a barge with a little house on top.”

The Floating Theatre, he recalled, carried a cast of a dozen or so, a seven-piece orchestra, and a cook or two, as well as the crews for the barge and the two tugboats that towed the barge from town to town.

Everyone did more than one job. Our clowns here might have served as ushers before the curtain went up, might have played a banjo and fiddle on stage between acts, and then helped with a play’s special effects when they were not on stage.

The boat’s theatre had room for about 400 persons when this photograph was taken in 1940.

-5-

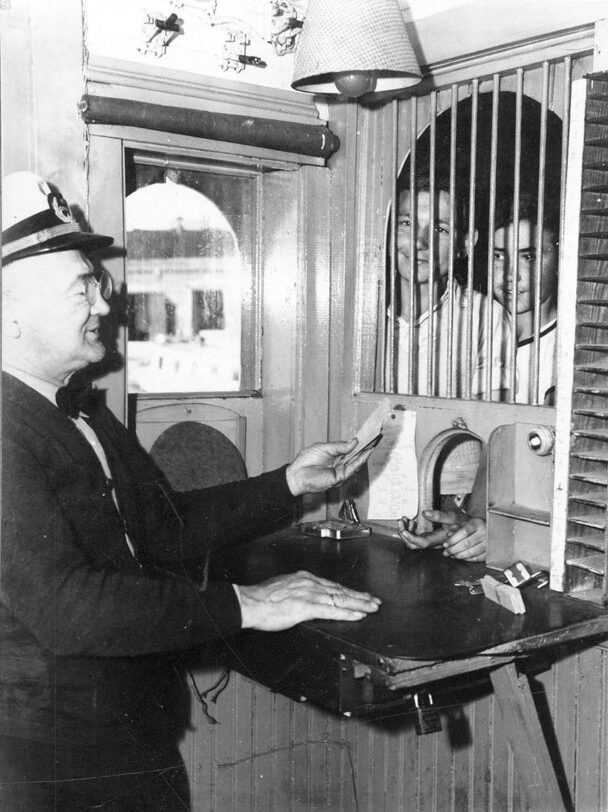

Here we see the Floating Theatre’s captain taking tickets before a show.

-6-

And here we see one of the Floating Theatre’s actresses ironing a costume before that night’s show.

-7-

By 1940, times were catching up with the James Adams Floating Theatre. By then, at least in larger towns, the public could go to a movie theater and watch the latest Hollywood films.

More and more people also owned radios and record players. In many larger coastal towns, you could walk through the streets and hear all kinds of music coming out of people’s windows — Big Band music, jazz, opera and the latest dance numbers from New York City.

Many people also religiously followed their favorite radio dramas, comedy shows, and soap operas, at the time as well.

Perhaps by 1940, some of the novelty of the Floating Theatre was wearing off. It was getting easy to forget the thrill and excitement that the arrival of the James Adams Floating Theatre had given audiences in its early days, especially back in the 1910s and ’20s.

Built in 1913, the Floating Theatre was built in 1913 and had first begun traveling coastal waterways in 1914.

Over the years, as I have done historical research on other subjects, I have often been surprised at the places where I found the Floating Theatre’s troupe of players performing on the North Carolina coast.

The Floating Theatre’s players regularly staged shows in the state’s larger seaports, such as Washington, New Bern, and Elizabeth City. But the troupe also visited little coastal villages such as Winton, Murfreesboro, Bath, Bayboro, Oriental, Swansboro, and many others.

I even stumbled on the Floating Theatre hosting shows at a very remote lumber mill village on Juniper Bay, 10 or 12 miles east of Swan Quarter. The mill village was so small that it vanished when the mill eventually shut down.

In those sorts of places, even in 1940, theaters were few and far between, radios were uncommon, and most weren’t even on the old medicine show and traveling circus circuit.

When the Floating Theatre tied up at a wharf in a place like Juniper Bay, people came from far and wide to its shows.

They’d drive all day in a horse and cart or crowded into a farm wagon. They put down their saws and tromp out of the log woods. They’d close the schoolhouse’s doors and declare a holiday, all for the chance to see a show and laugh, forget their troubles, and feel things deeply.

As best I can tell, the Floating Theatre’s troupe welcomed one and all to their shows, as long as they could buy a ticket. To abide by the Jim Crow code of the time though, the ushers had no choice but to segregate white customers from those who were African American or Native American.

That was the law of the land and there were no exceptions, at least not in the light of day.

As the old saying went, “after midnight there was no black or white,” and truer words were never spoken.

-8-

In this last photograph in this series, we meet Rose Teal, the James Adams Floating Theatre’s cook.

Teal was evidently the kind of person who believed in preparing for the worst.

A year or two earlier, the Floating Theatre had hit a snag and sunk on the Roanoke River. I believe that the accident occurred while being towed from Murfreesboro to Williamston.

At the time, a newspaper reporter wrote, “Best prepared of the passengers was Rose, the cook, who has been with the show boat for the past six years. Rose, on the weekend trips from place to place, not only sleeps fully clothed and shod, but has all her belongings neatly done up in cardboard boxes.”

The reporter continued: “Her cabin was down under the stage, but she was among the first to reach the top-side, though how she and her collections negotiated the narrow stairway, was inexplicable.”

Nobody was hurt when the Floating Theatre went down. The boat was soon refloated and, as they say, the show went on.

Nevertheless, I can understand Rose Teal’s caution. That incident was at least the third time that the James Adams Floating Theatre had gone down.