The historic Whalehead Club in Corolla, a Currituck Banks landmark, will turn 100 years old next month and ticketed events commemorating the centennial are on sale.

Completed in 1925, the Whalehead Club, the majestic 21,000-square-foot art nouveau mansion and centerpiece of Historic Corolla Park, was completed after three years of construction. Its $383,000 price tag at the time is about $7.1 million in 2025 dollars.

Supporter Spotlight

The 33 years that Currituck County has owned the property is the longest period it has gone without changing hands.

After more than three years of negotiations, the county purchased Whalehead in November 1992 from Howco Residential Development Inc., which had foreclosed on the property in 1989. That was after the failure of two savings and loan institutions, which had previously owned the property, according to a 1992 report in the Coastland Times.

Although Whalehead is now again a symbol of wealth and opulence on Currituck Banks, at the time of the county’s purchase, it was dilapidated and a shell of what it had been when construction finished 67 years earlier. Its 1992 price tag of $2.8 million included the building and 28.5 acres, and the purchase was extraordinarily unpopular with county voters. Every commissioner on the 1992 board that bought the property lost their reelection bid after the purchase.

“Most people didn’t understand what we were doing,” Jarvisburg resident Jerry Wright, who was a county commissioner at the time, recently told Coastal Review.

Whalehead was like nothing the Outer Banks had ever seen.

Supporter Spotlight

Multimillionaire industrialist Edward Collings Knight built the mansion as a vacation getaway and hunting refuge for himself and his wife Marie-Louise LeBel.

It had an elevator and a basement. Elevators were unheard of here, and the basement was an engineering feat for a building so close to sea level. Two Delco-brand generators provided electricity at all times.

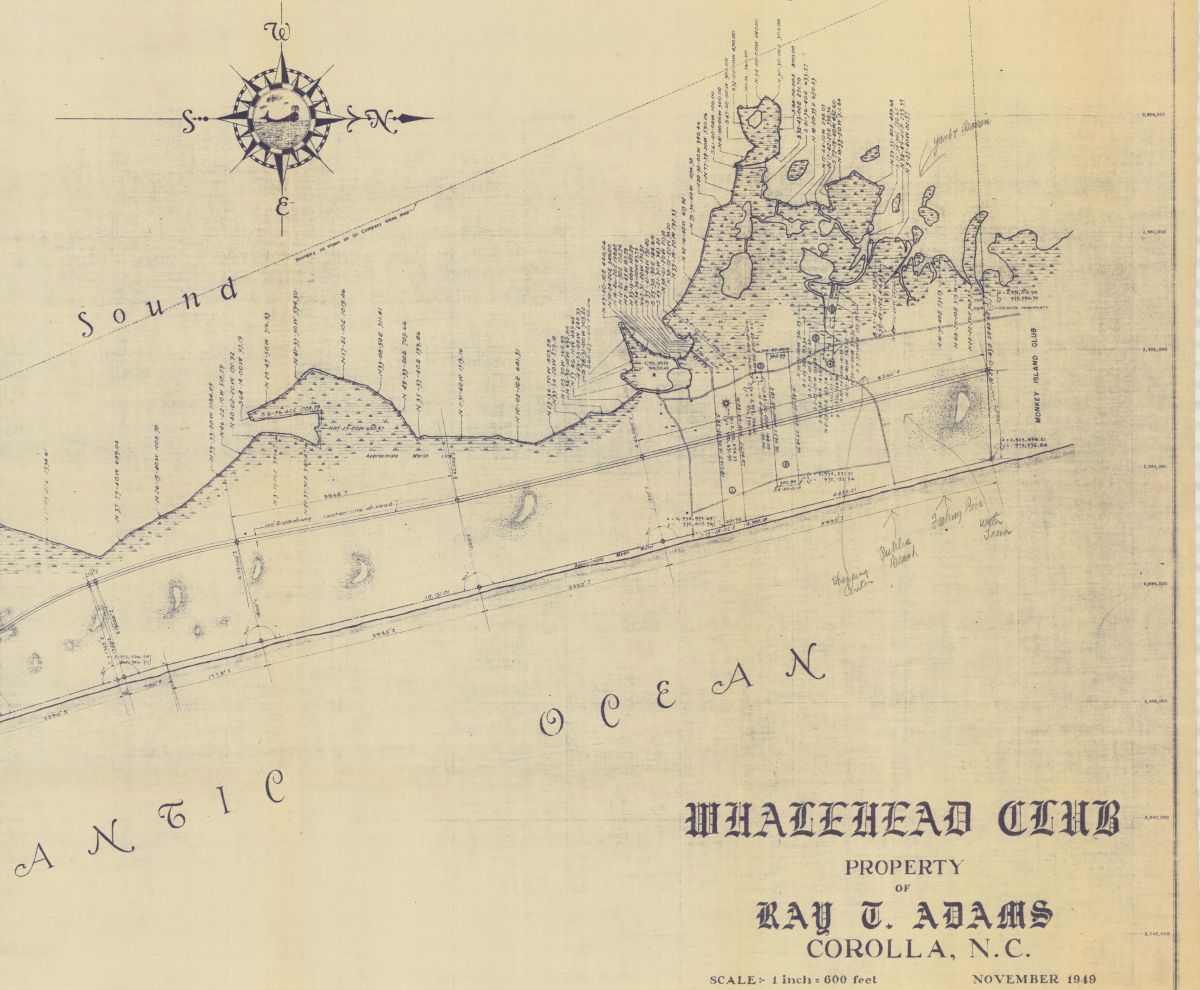

The Knights named their Currituck Banks getaway cottage Corolla Island, a reference to the artificial island that was created by dredge and fill so the ground could support the massive building.

“The main house was erected on a hill formed by the earth dredged to create the moat. The hill made it possible for Whalehead to have a full basement that rests on sunken wood pilings, a feature that is considered extraordinary for a coastline structure,” notes the 1978 Register of Historic Places documentation.

Until 1922, the 2000-acre property had been owned by the Lighthouse Club, one of Currituck Sound’s most exclusive hunting clubs of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Although there are legends that Knight bought the Lighthouse Club after his wife, who was an avid hunter, was not permitted to hunt because of her gender, there is no evidence to support the claim.

According to a 1986 letter provided by the Whalehead Club and written by John B. Litchfield, Corolla Island was built by a local contractor and the plans for the building were somewhat vague.

“Mr. Knight, who had had training in art, drew the plans for the house,” Litchfield wrote. “He did not, however, include any specifications. I do not know who recommended my father as a builder, or how they got together. At any rate, Mr. Knight contracted with my father, J. A. Litchfield of Poplar Branch, N.C. to build the house.”

Litchfield’s observation that Knight’s plans did not “include any specifications” is consistent with the belief that Knight did not use an architect to design the house, in spite of the project’s complexity.

The Knights stayed at Corolla Island for extended periods over the next nine years, entertaining a number of guests. The last entry Edward Knight recorded was Nov. 24, 1934. Edward Knight died on July 23, 1936, and his wife Marie Louise died three months later.

This was during the Great Depression and Knights’ heirs had no interest in maintaining a vacation getaway and hunting lodge on the Outer Banks. They auctioned off many of the one-of-a-kind Tiffany designs in the houses and other art nouveau objects and started looking for a buyer.

Rep. Lindsey Warren, who represented northeastern North Carolina at the time, told his congressional colleagues about the property, and New York Rep. William Sirovich agreed to purchase it for $175,000. The closing date was to be Dec. 17, 1939, the same day Sirovich died suddenly.

Ray Adams, a Washington, D.C., meat packer with considerable political connections, instead bought the property for $25,000 in early 1940.

It was Adams who gave the property its name.

“According to tradition, in the process of clearing land for the air strip that would facilitate transportation of guests, a whale bone was found which prompted Adams to rename his estate Whalehead Club,” the National Register of Historic Places notes in their documentation.

Although a whale bone may have been found when an airstrip was being built, there is reason to believe the area was already sometimes referred to as “Whalehead.”

An August 1926 article in the Elizabeth City Daily Advance headlined “Currituck Girls Enjoyed Camping Trip” reported that the young women had “just returned from their summer camping trip at Corolla, that part of the beach known as Whalehead.”

Adams had big plans for his newly purchased property. Although interested in hunting, “his major motivation for acquiring the 2000-acre estate was to use it for entertaining the government officials who controlled the contracts that provided the bulk of his business,” according to Historic Register documents.

Adams on Nov. 1, 1940, formed Whalehead Club Inc. with 10 shares mostly held by Adams and his wife.

Knight’s plans for an entertainment center, though, were put on hold when the United States entered World War II and the Coast Guard needed a training and patrol site.

In 1942, Knight agreed to rent the Whalehead Club to the Coast Guard. Barracks were built, which no longer exist. At one time, up to 300 Coast Guardsmen were stationed at Corolla.

Adams, concerned about protecting his property, included a provision that his club superintendent, Dexter Snow, be made a chief bosun’s mate and be stationed at Corolla to look after his interests.

After the war, Adams threw himself into his plans to create a luxury resort on Currituck Banks.

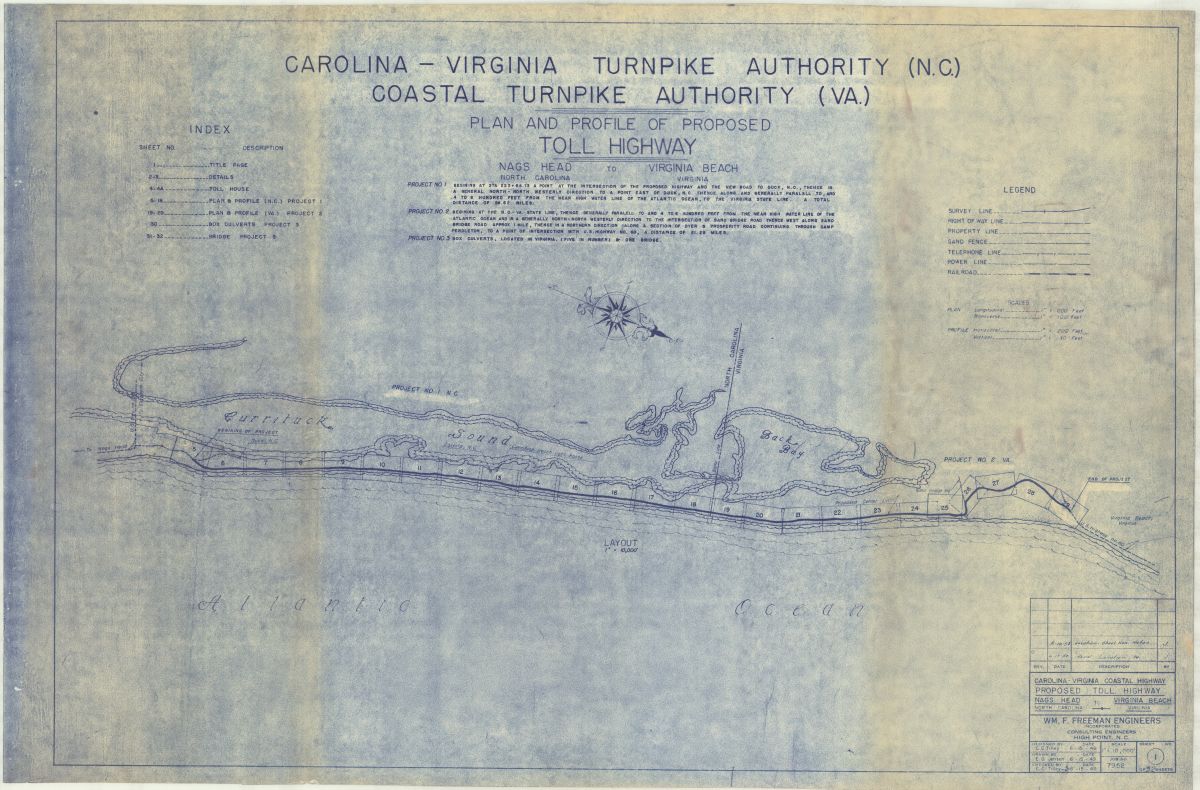

“He was kind of promised a toll road that would go … like a Route 12, but all the way up to Virginia along the beach,” said Whalehead Club Curator Jill Landon. “He wanted it to be like a Myrtle Beach or kind of like an Ocean City, Maryland. We’ve got the plans drawn up with like a Ferris wheel and all sorts of infrastructure up here.”

Using his government contacts, Adams began lobbying for a beach toll road.

Adams’ plans relied on the toll road to make the project feasible, but the concept he had in mind was extensive.

The plans are on file with the Olmsted Archives at Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. Listed as Job No. 10031, Whalehead, the documents drawn for Adams by Olmstead Brothers Landscape Architects clearly show a planned toll road with a 100-foot right-of-way, a yacht basin, shopping center and fishing pier, among other amenities.

The Carolina Virginia Turnpike Authority, or CVTA, was formed, but problems soon emerged.

Dare County Rep. Bruce Etheridge introduced a bill in the House for the “five-year-old beach toll-road project,” reported the April 17, 1953, edition of the Coastland Times.

The bill was doomed. The authority had been given powers of eminent domain, but the state Supreme Court, the article noted, had “opined that the Legislature could not give a company municipal powers nor the right to condemn private land.”

The authority also found there was little appetite in the bond market for a toll road that would cross state lines and require approvals from two states. In December 1954, the Coastland Times reported that “The sponsors of the Nags Head-Virginia Beach toll road still have not sold their bonds.”

The problem, CVTA authorities explained, was “the fact that two separate authorities and two states are involved has created legal problems which must be clarified before the bonds are sold.”

Two years later, in August 1956, it had become clear that the toll road was not going to happen. Adams’ dream of creating a sprawling resort community along the Currituck Banks was never realized.

The last entry in the Whalehead Club log recorded “that Adams died there suddenly at 6:10 p.m.,” according to the Historic Places documentation. That was Dec. 31, 1957.

The heirs to the Adams estate were able to quickly find a buyer. Portsmouth, Virginia, contractors MacLean and Wipp paid $375,000 for the estate and in turn leased the building and immediate grounds to the Corolla Academy.

The Corolla Academy had a clear vision of how the education of young men should proceed.

The Historic Places document quotes from a brochure to parents: “Corolla Academy is the result of the firm conviction that summer study for boys of secondary level is a rewarding and enjoyable experience. The time has passed when American boys can afford to waste the three months’ interval between the end of school in June and the resumption of classes in September.”

It’s not clear if it was location, philosophy or some other reason, but the Corolla Academy closed after three years.

What followed may be one of the more intriguing uses of the Whalehead Club.

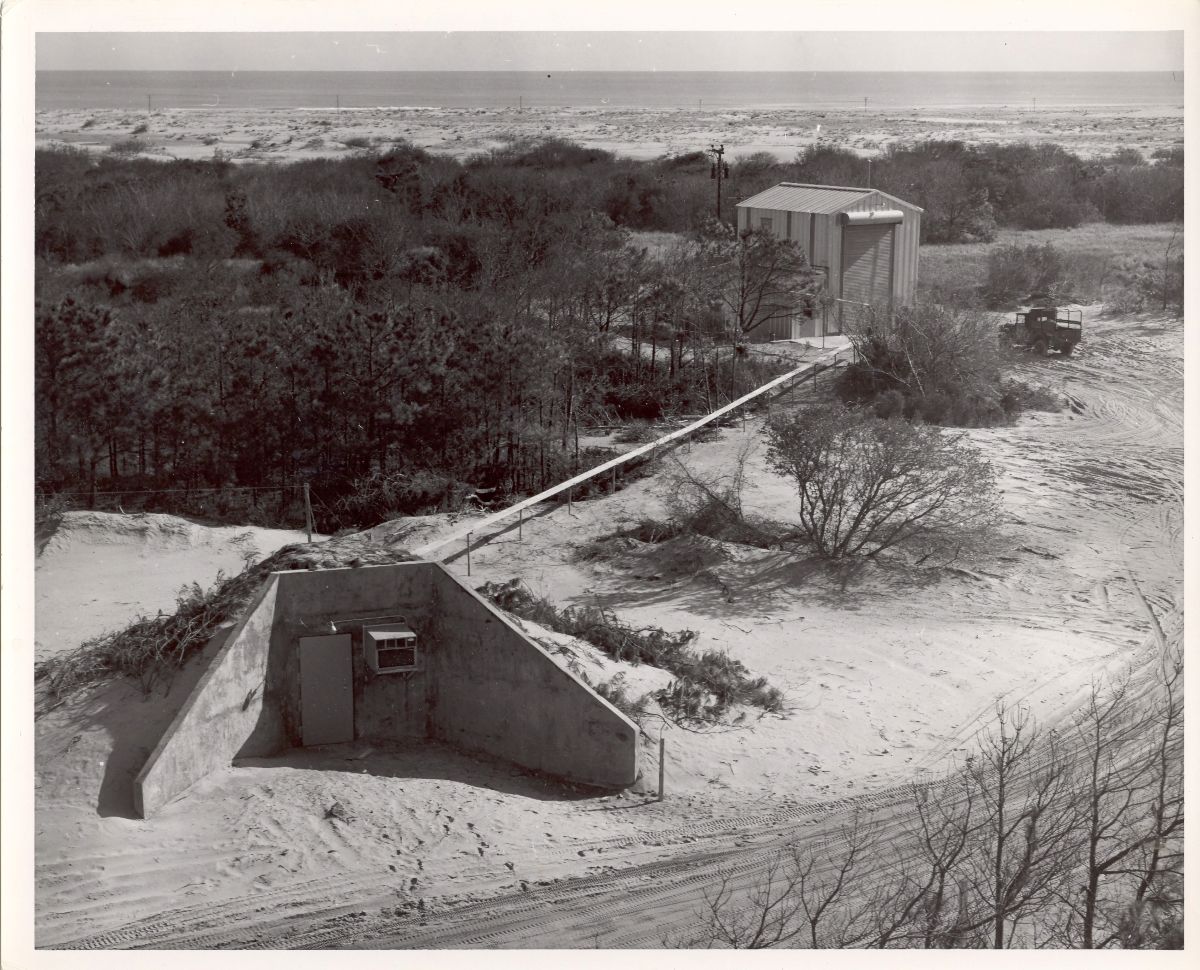

The United States was in a frantic race in 1961 with the Soviet Union to be the first nation to land on the moon, and Atlantic Research Corp. was in the thick of it, designing rocket engines for NASA. The Soviet Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR, existed from 1922 until 1991 in eastern Europe and northern Asia.

The corporation, or ARC, leased the estate from Wipp and MacLean with a $1.25 million option to buy that was exercised in 1964. For ARC, the Whalehead Club was ideal for its purposes.

ARC was experimenting with beryllium as a fuel for the Poseidon rocket engines. As a fuel, beryllium has some real advantages. It’s very powerful and it’s relatively stable, although it is extremely toxic.

It became apparent that beryllium was not going to be a practical fuel, and in 1972, ARC sold the property to local Norfolk real estate developers Kabler & Riggs for more than $3 million. That firm subdivided the property but left the 35 acres around the Whalehead Club building intact.

The building was left vacant for 20 years, but as noted in the Historic Places 1978 report, the building, with its I-beam construction and 18-inch-thick walls, had been “successfully constructed to withstand the most severe coastal storms.”

Obligated to pay off the loan for the 1992 purchase of the property, Currituck County was not able to begin a full restoration of the building until 1999, when 25% of occupancy tax collections could be used.

In 2002, 10 years after the property had been purchased, the Whalehead Club opened to the public.

The original custom Steinway piano was inside and some of the original Tiffany sconces were still intact. Careful research of auction records had enabled the team working on restoration to track down a surprising number of original furniture pieces. By the time it opened to the public, the county had spent more than $1 million in restoring the building.

The Whalehead Club is available for tours. Reservations are recommended and can be made by calling 252-453-9040 ext. 226, at the site or online.