From the editor: Kip Tabb, who resides on the Outer Banks and writes for Coastal Review and other regional publications, documented his recent walk along the Freedom Trail at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

The Freedom Trail on the north end of Roanoke Island is a beautiful walk through history. A history that is both uplifting and troubling.

Supporter Spotlight

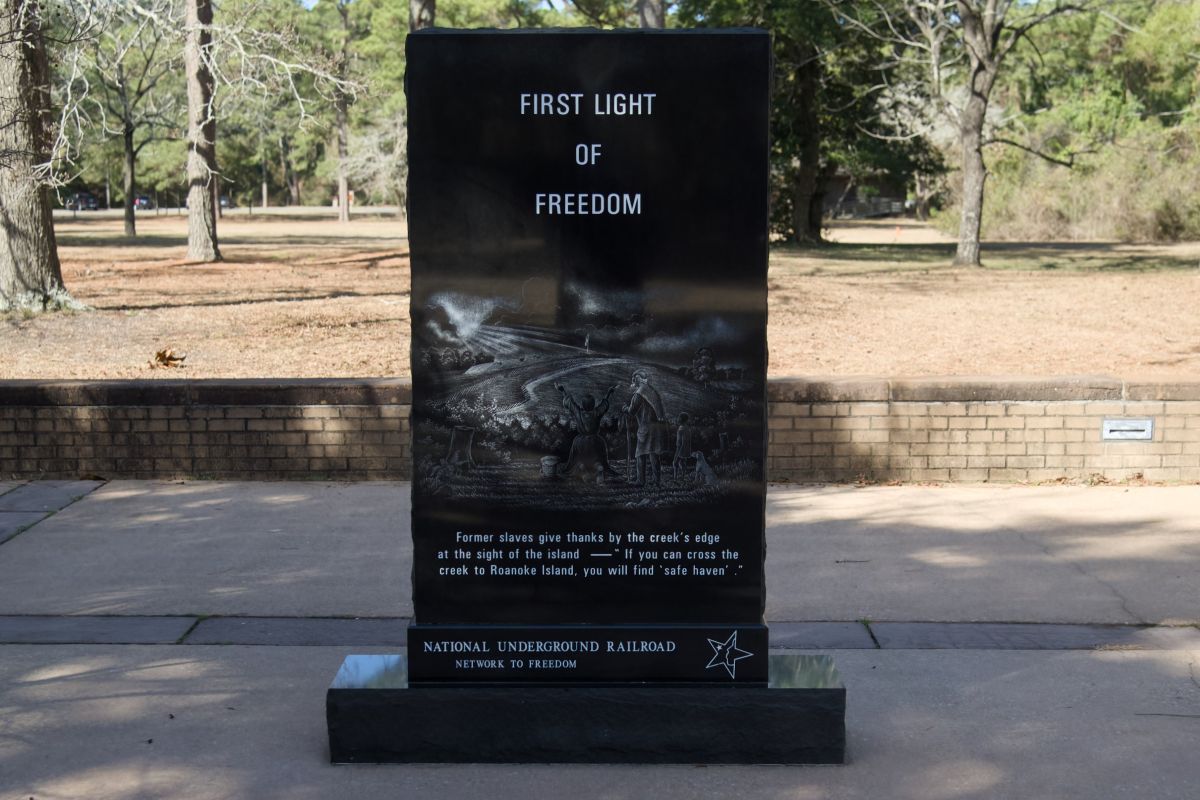

Beginning at the visitor center of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, the trail is an easy 2.5-mile out and back hike through a verdant maritime forest that ends at Freedmen’s Point on Croatan Sound.

Depicting the story of the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island, interpretive signs along the path give details of what life was like there. Metal silhouette statues stand behind the signs in silent testimony to the tale that is told.

The Freedmen’s Colony is the story of the enslaved people who came to Roanoke Island desperate for freedom and hope.

It is a story that is interwoven with the men and women who came from the North to help an illiterate population learn to live in a free society.

After Union forces seized Roanoke Island in February 1862, enslaved people came by the hundreds and even thousands to the island, seeking refuge and freedom.

Supporter Spotlight

At first, the men and women who had escape bondage were called “contraband.” Because the South was in rebellion against the North, any property seized was considered contraband of war.

In the South, enslaved people were considered property and based on that premise, they were not returned.

Even before President Abraham Lincoln’s Jan. 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people behind Union lines were considered free people.

In 1863 the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony was officially established. It was the first in North Carolina and one of the first in the nation. At its peak, according to an 1864 census, it had a population of 3,901.

In 1867 it was disbanded.

About the trail

Along the trail are eight interpretive signs and nine silhouettes that represent individuals who lived and worked at the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island, according to the National Park Service.

The trail was unveiled June 1, 2024, during a ceremony organized by the National Park Service and the Dare County Trails Commission.

The sign, “Roanoke Island Before 1862,” with silhouettes representing Annice Jackson and her daughters, Marie and Alice in the background, highlights Marie Ferribee Watkins, who “was born enslaved in North Carolina. Through the strong will of her mother Annice Ferribee, she was able to become part of the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony. After beginning formal education at the colony, she went to present-day Hampton University, becoming a college graduate and eventually an educator,” the National Park Service website states.

The nine silhouettes represent different people who were part of the history of the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island.

When war came to Roanoke Island, Thomas Robinson who grew up enslaved on Hatteras Island, helped Union forces navigate the local waters.

He never officially was part of the Freedmen’s Colony, but stayed with Gen. Ambrose Burnside throughout the war. Afterwards, records show he moved to Rhode Island.

The thirst for literacy was intense among the residents of the Freedmen’s Colony. During its time on Roanoke Island, 10 schools were established.

“Arriving on Roanoke Island as an illiterate fourteen-year-old boy and leaving three years later as an accomplished scholar and educator, Reverend London L. Ferebee exemplifies how many Freed people used the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony as a springboard into emancipated life,” according to the park service.

As the colony became established, missionaries from the north came to teach in schools and spread the Gospel. Of particular note was Horace James.

“Horace James was an evangelical minister from Massachusetts who served as a Union Army chaplain and director of the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island. A graduate of Yale University, James enlisted as Army chaplain of the Twenty-Fifth Massachusetts Volunteers on October 29, 1861. In April, 1863, Major General John G. Foster appointed James “Superintendent of All the Blacks” in the Department of North Carolina. Based in New Bern, James was put in charge of the colony,” according to the park service.

In May 1863 the US Colored Troops was formed and many of the men of the Freedmen’s Colony enlisted, among them were Richard Etheridge, who went on to be the Pea Island Lifesaving Station Keeper and Spencer Gallop.

“Spencer Gallop worked on Roanoke Island cutting down trees for the Union forces after the Battle of Roanoke Island. When the Army began recruiting on the island, Spencer enlisted and served in the 36th U.S.C.T. becoming one of the first official Black soldiers in the U.S. Army,” according to the park service.

Religion was a central part of the Freedmen’s Colony experience. The enslaved people were educated by missionary women from northern churches and African American pastors from the AME and AME Zion churches.

Sarah Freeman stayed on Roanoke Island after the Civil War ended to help the formerly enslaved people navigate a life of freedoms. She left in 1866.

“Despite being one of the oldest teachers at age 51, Sarah Freeman’s remarkable dedication during her time as a teacher at the Freedmen’s Colony of Roanoke Island distinguished her as a resilient and industrious woman. Even when she was stricken with malarial fever and confined to her bed for a period, Freeman persisted in her unwavering efforts, alongside her daughter, to tirelessly distribute food and clothing to the formerly enslaved individuals on the island,” the park service says on the website.

The federal government broke their promises to the people who had come to all Freedmen’s Colonies.

“This colony, similar to others established by the Union army, gave African Americans their first tastes of independence and freedom. However, like other sites, it was short-lived and soon faded from the pages of history,” states the park service website.

Although the government had promised land and farming equipment to the residents of the Freedmen’s Colony, with Andrew Johnson as president, those promises were withdrawn and support for all Freedmen’s Colonies severely curtailed. By 1867 the Roanoke Colony was disbanded.