ROANOKE ISLAND — While immigration is a hot election-year topic, it’s perhaps notable that speculation continues unabated about the fate of America’s first English immigrants who vanished into the mists of history 437 years ago, with yet another twist in the saga of the real people who became known as the “Lost Colony.”

Could at least a group from the colony that briefly settled on the shores of today’s Roanoke Island, on North Carolina’s Outer Banks, have moved, not only 50 miles south or west, as many believe, but simply to the other side of the sound?

Supporter Spotlight

According to records, when the colony’s governor John White returned three years after he left for supplies in 1587, the only evidence of the colony’s whereabouts was the word “Croatoan” – once the home of the Croatan Indians on Hatteras Island – carved on a fort palisade, and the letters “CRO” carved in an oak tree. That has been widely interpreted as a signal from the colonists that they moved to Croatoan – that is, Hatteras.

Alternately, there were signs that could have meant they went 50 miles into the mainland, as White said was discussed with the colonists before he departed.

But in a recent research report, “Croatan: The Untold Story,” veteran archaeologist Eric Klingelhofer, vice president of research with the nonprofit First Colony Foundation, says that a review of historic maps indicates that the Croatan tribe who had befriended the Roanoke colonists did not actually live on Hatteras Island; they lived on land across from Roanoke Island at what is now mainland Dare County. So if at least some colonists went to live with the Croatan Indians, they may have had to merely cross the sound.

“Cartographic study therefore suggests that a broad territory was attributed in the historical period to the remnant Croatoans, and that the likely location for their core habitation and Dasemunkepeuc itself lay northwest of Roanoke in the vicinity of modern Mashoes,” Klingelhofer asserts in the report, published on the foundation’s website.

Dasemunkepeuc, an Algonquian village, was located at present-day Mann’s Harbor, near Mashoes. The Croatan and Roanoke were branches of Algonquian Indians.

Supporter Spotlight

What his research shows is that the Croatan had left Buxton on Hatteras Island at some point after the arrival of the English in the mid-1580s, and relocated to the mainland where they could grow crops, Klingelhofer, a retired professor of history at Mercer University, told Coastal Review in a recent interview.

“It looks like, from these maps, which were most of the official governmental maps, that the Mashoes area and south of that Manns Harbor area was the land of the Croatoans,” he said, using an alternate name for the Croatan. “The Roanokes, who probably had more problems with disease because they had greater contacts, they may have been there for a while. But then they moved south, maybe because of better resources, or there were more friendly natives that they had relations with, or something like that. And then they don’t know what happened to them beyond the fact that they were no longer in this area.”

Long catnip for charlatans, fabulists and conspiracy dabblers, the disappearance of Sir Walter Raleigh’s colony on Roanoke Island – England’s first attempted settlement in the New World – has been dubbed the “nation’s oldest mystery” for a reason: Only bits of evidence have been found that point to what may have happened to most of the 117 men, women and children who had sailed to Roanoke Island more than four centuries ago.

Perhaps because of its ephemeral intrigue, the Lost Colony, a precursor to Jamestown in 1607, the first permanent English settlement, has been the focus of numerous archaeological surveys and digs – both professional and amateur – for decades. It has sparked a beloved long-running local summer theater production. It has spawned magical fables of a White Doe and of large stones carved with cryptic writing, both linked to Virginia Dare, a colonist’s baby born in 1587. And it has inspired many books, some more authoritative than others, including Klingelhofer’s, “Excavating The Lost Colony Mystery, The Map, the Search the Discovery,” published in 2023 in association with the foundation, which features a collection he edited of research by historians, archaeologists and others.

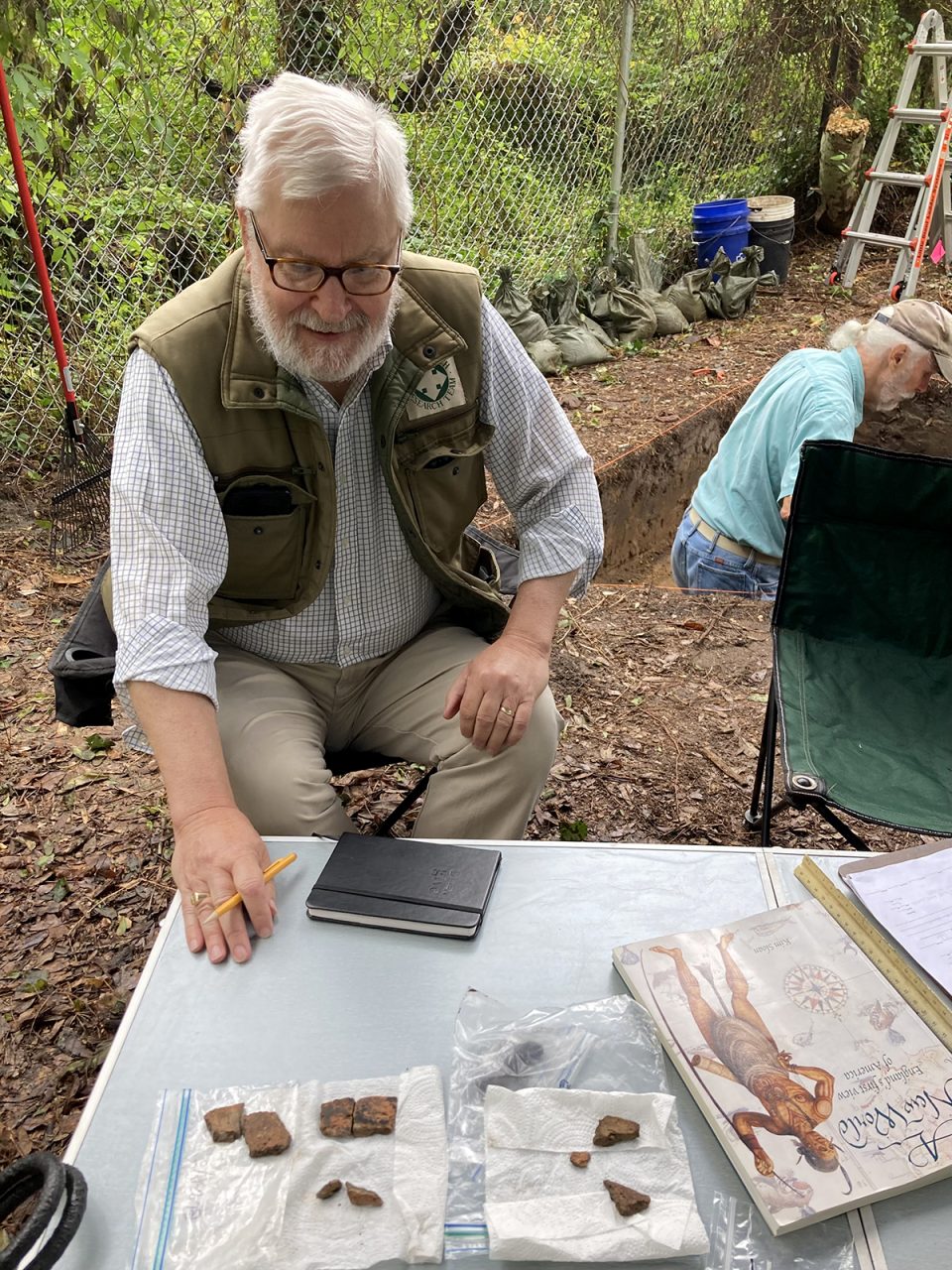

The foundation has worked closely with pre-colonial experts who have conducted research at Williamsburg and Jamestown in Virginia, as well as at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island, which has yielded artifacts but no hints of the colonists’ settlement. In a recent archaeological exploration, the foundation had found evidence of first contact between the English explorers and Native Americans at Fort Raleigh, and also has unearthed artifacts that indicate some Lost Colonists may have lived for a time at riverfront sites in Bertie County, dubbed Site X and Site Y.

Despite the growing volume of information that has been collected over the years, and numerous Indian and English artifacts that have been unearthed, to date no pre-colonial smoking gun has been found that fills in the big blanks about the elusive Lost Colony.

“We don’t know where they started out from,” Charles Ewen, distinguished professor of anthropology at East Carolina University’s Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences, told Coastal Review. “We don’t know where they went. We have sort of the general vicinity and it’s become this wonderful mystery that people are trying to figure out.”

Ewen, more cohort than rival of Klingelhofer, has also recently written a book, with co-author E. Thomson Shields Jr.: “Becoming the Lost Colony, The History, Lore and Popular Culture of the Roanoke Mystery,” published in 2024.

Whatever detritus the colonists left behind may have been lost to erosion along the shores of the Croatan Sound or to decay in the swamps. But there are also unanswered questions about 16th century people’s choice of living conditions, and Ewen agreed that the mainland could have provided better shelter and more food.

“In fact, I think most archeologists think that the Outer Banks were just seasonally occupied,” Ewen said. “So when they said they were prepared to move 50 miles into the main, I think the Outer Banks during the winter would not have been a terribly hospitable place.”

Deciphering the clues of the Lost Colony, like a 400-year-old board game, is why the mystery of their fate continues to fascinate.

Klingelhofer, a founding member of the First Colony Foundation, a volunteer group of professional archaeologists established in 2003, has explained that their overall mission is finding evidence to fill in the gaps about the 1584-1587 Roanoke Voyages, which ultimately led to early American English colonization. Still, it’s always the Lost Colony story from the 1587 Roanoke Voyage that most ignites the public imagination and spurs continued investigations and research, such as Klingelhofer’s work.

Both Klingelhofer and the foundation, and Ewen and East Carolina University, have a close association with the late archaeologist David Phelps, professor emeritus of anthropology at ECU who died in 2009 at age 79.

An expert on prehistoric and Algonquian archaeology, Phelps was renowned for his work studying Tuscarora Indian sites at Neoheroka in Greene County and Jordan’s Landing in Bertie County. When Hurricane Emily in 1993 exposed vast amounts of pottery sherds and shell midden in Buxton, it was Phelps’ numerous excavations that determined the site had been the Croatan capital that stretched a half-mile from Cape Creek to Buxton village.

Phelps had dated what he called “the Hatteras site” from 1650 to 1720.

Manteo, who had befriended the colonists, had lived in Croatan, and his mother was the tribe’s leader. For that reason, some historians hypothesized that the colonists may have fled there, although most say the Croatan had inadequate food and space to accommodate more than a small number.

An archaeologist who had worked alongside Phelps as a young man, Clay Swindell, is now working with the foundation, Klingelhofer said.

Even though centuries separate our contemporary population from historic colonial explorers, human nature was likely as prone to boasting and deception then as it is now.

Hence, Klingelhofer said it’s worth noting that everyone is presuming what White, the governor who reported the “CRO” letters at the Lost Colony’s fort, actually knew and didn’t know.

“John White wasn’t always trustworthy,” he said. “He assumes a lot of things. He claims a lot of things that are not necessarily fully the truth. A lot of it is his interpretation of particular people and their motives behind the people that he has gotten angry with.”

In other words, White’s account may not be the only version of Lost Colony history to consider.

“But any good historian knows better than to trust a person who’s even an eyewitness to things,” Klingelhofer said. “You need corroboration. And sadly, there isn’t any except for in these maps.”

As Ewen sees the Lost Colony, all of the foundation’s hypotheses could be legitimate, but as he and Klingelhofer agree, it’s all pieces of a puzzle yet to be solved.

“I think it’s very difficult to say with any degree of certainty, until we find some more physical evidence, that we have an idea of what happened,” he said. “We need to find Christian burials from the 16th century, and I think that will really start putting us in the vicinity.”

English burials, he added, would be east-west, with the head at the west end. The clothing items would date to the 16th century, and skeletal analysis would indicate they were European. But archaeologists and historians are by no means ready to throw in the towel in pursuit of the Lost Colony.

“Honestly, I think it’s going to be an accidental discovery,” Ewen said. “Somebody will come across something while they’re developing … (and) stumble upon some of this stuff. And the archeologists will get involved, and then it will be, ‘Oh, OK!’”