As a young adult right out of high school, I had just finished what I hoped would be my last summer suffering in the hot farm fields harvesting tobacco.

It was late August and I headed to Hammocks Beach State Park near Swansboro to cool off in the waters off of Bear Island. A secret spot, available only by boat, that I had heard about, but never been to. Arriving late in the day, the ranger that was piloting the passenger ferry told me it was the last run of the day. Instead of sending me on my way, he invited me ride to the island with him.

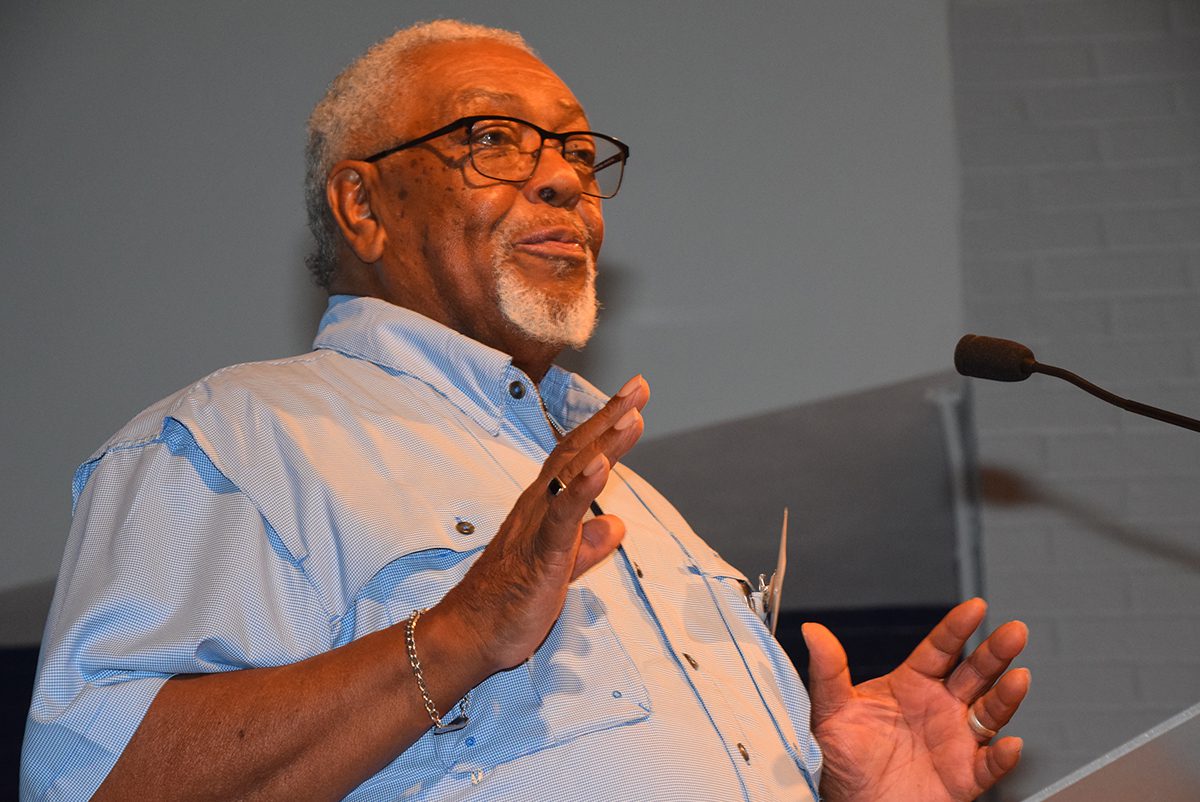

Supporter Spotlight

Docking on the sound side of the island, he gave me 20 minutes, just enough time to run the trail to the ocean. I bodysurfed a couple of waves, admired the magnificent beach and sand dunes, then raced back to the dock. The ferry returned to the mainland with a load of sunburnt, sand-crusted beachgoers and I headed off to college. Little did I know at the time, that this ranger would become someone that I admire, respect and have been fortunate to call a friend.

Four years later, in the fall of 1980, I am a newly hired ranger at Fort Macon State Park. I hadn’t forgotten the kindness of this ranger and now, as a ranger myself, I was eager to repay the debt. During my first few months at Fort Macon, I heard a number of stories about the superintendent at Hammocks Beach, Claude Crews, and his stature only grew.

The following summer, I was assigned to help out at Hammocks Beach for a few days due to staffing issues. I jumped at the chance to meet Superintendent Crews, commuting the 35 miles from Fort Macon to Swansboro. To get me familiarized with Bear Island and its park operations, Crews took me on a thrilling boat tour of the soundside backwaters along with a four-wheel-drive excursion on the island.

This was a man in his element. His knowledge and passion left a lasting impression on me, along with a hidden desire to one day follow in his footsteps.

Superintendent Crews had been the guardian of Bear Island long before I formally met him as a fellow ranger. Off the beaten path and accessible only by boat, Bear Island was, and still is, one of the crown jewels of the North Carolina State Parks system. A pristine barrier island of natural and cultural significance, how the island became a state park, is in itself, an amazing story of a colorblind friendship and generosity.

Supporter Spotlight

In 1914, the renowned, pioneering neurosurgeon William J.C. Sharpe went on a duck hunting retreat with the Onslow Rod and Gun Club in the marsh waters of coastal North Carolina.

He stepped onto a boat piloted by his guide, John Hurst. Cultures collided as Hurst, an African American and the son of an enslaved man, met the Harvard-educated, internationally distinguished medical doctor. This “chance encounter,” as Dr. Sharpe described it, ignited a close friendship that lasted for decades and created an enduring legacy.

In the brain surgeon’s autobiography, Sharpe described Bear Island as such, “… a four-mile stretch of Atlantic beach, wide, level, and firm enough to permit the landing of airplanes — another Daytona.”

Dr. Sharpe also owned many acres on the mainland, a “peninsular wonderland” known as “The Hammocks.” He purchased the properties as his personal retreat sometime around 1920 and recruited John Hurst and his wife Gertrude as caretakers of the land. This was a bold decision in the heavily segregated South near a town that had a reputation as a “sundown town,” meaning Black people were not allowed after dark. Pressured to remove Hurst as the property manager, Sharpe notes in his book, “I refused to make the change.”

An advocate of civil rights, Sharpe was deeply disturbed by the injustices of segregation that deprived African Americans of basic rights. Later in life, he wanted to gift “The Hammocks” properties to the Hursts for their years of loyal service and friendship. In discussions with Gertrude Hurst, a retired school teacher, a plan was hatched to gift the property to the North Carolina Teachers Association in 1950.

Recognizing the need for recreational and educational opportunities for African Americans along the coast, the teachers association formed the Hammocks Beach Corp. The corporation managed the property providing a “resort” where African Americans could freely enjoy going to the beach, swimming, fishing and camping. It essentially served as its own segregated private park.

Looking for long-term management and protection of Bear Island, the Hammocks Beach Corp. negotiated with the state for the island to be included in the state park system. In 1961, Hammocks Beach State Park became one of only three state parks in North Carolina exclusively for Black people. The other two being the Reedy Creek section of the William B. Umstead State Park and the Jones Lake State Park.

Accustomed to hard work

Born in 1941 in Wake County, Claude E. Crews grew up accustomed to the hard work associated with running the family farm. After high school he attended Shaw University with an interest in elementary education. However, he had a chance encounter that changed his course.

One day while at his grandfather’s farm, a state engineer showed up to do some work for his grandfather. The two started talking and the engineer suggested that Claude apply for a job with the Division of State Parks, and the rest, as they say, “is history.”

Crews first donned the proud colors of the gray and green ranger uniform in 1963 with an appointment at the then-recently christened Hammocks Beach State Park. It was now on his shoulders to carry on the legacy of Dr. Sharpe and John and Gertrude Hurst.

Nine years had passed since deadly Hurricane Hazel swept over Bear Island in 1954, and its devastation was still visible when Ranger Crews stepped onto the island for the first time in his official capacity. The overwash and salt spray from this Category 4 hurricane scorched the island as if by wildfire. The island was barren with dead trees and grasses and new vegetation was struggling to take hold.

Ranger Crews put his farming expertise to good use, planting thousands of native trees and shrubs. Many of the live oak trees you see on the island today were carefully nurtured by Crews, planted from tiny acorns.

Prior to the availability of commercially manufactured sand fencing, ranger Crews collected boatloads of wax myrtle branches from the mainland and brought them to the island. Here, he fashioned his own version of sand fence to tame the blowing sand. This ingenious fencing slowed down the sand, piling it up, creating dunes that rebuilt the primary dune line.

Ranger Crews then teamed up with Karl Graetz of the United States Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service to plant hundreds of thousands of individual sprigs of sea oats and beach grass to stabilize these growing sand dunes.

Bear Island was alive and green again.

Face of the park

As a young man with a new job, Crews went about his work managing the seasonal park operations, which included operating a passenger ferry service, bathhouse, concession stand and swimming area. He was the personnel and financial officer, maintenance man, mechanic and custodian.

As he began his park career, the dark cloud of segregation was still overhead and a Black man was still in charge of “The Hammocks.” Crews was not a local, yet, but he was now the face of the park. How would he be received by the community?

When Crews started at the park, Gertrude Hurst was still alive and living on

The Hammocks. He was a regular at the Hursts’ dinner table, enjoying her cooking. She attributed her longevity to eating fish every day, and Crews, who was not a fish eater, soon learned to love fish.

The welcoming friendship he received from her went a long way toward his broader acceptance by the locals, regardless of their race. But there was more: Crews’ character and calm demeanor were also key. He went about managing the park without any serious racial issues. Crews stated to me, “racial issues were not really an issue when I arrived at The Hammocks, any issues in the past had already been addressed by Mr. Sharpe.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1963.

In July 1964, with the passage of the monumental Civil Rights Act, the formerly segregated Hammocks Beach State Park was now open to all visitors regardless of skin color. In the first few years after the act, park visitors continued to be mainly African American.

Park Service administrators were a tad nervous when Ranger Crews hired white lifeguards to protect the ocean swimming area. Fearing racial conflicts, trips were made to Swansboro to inspect park operations. It was clear that Crews’ leadership and calm reassurance were respected and any worry of problems was unwarranted.

After a few years at the coast, Crews was briefly stationed at Jones Lake State Park in Bladen County before returning to Hammocks Beach. In 1966, Uncle Sam called his number and he was drafted into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. He pulled his two-year hitch and his job at Hammocks Beach was still waiting for him, but now, officially as the park superintendent.

After integration of Hammocks Beach, the beauty of the park was now a lure to all. This hidden jewel was beginning to be found. Crews guided the park for the next 13 years.

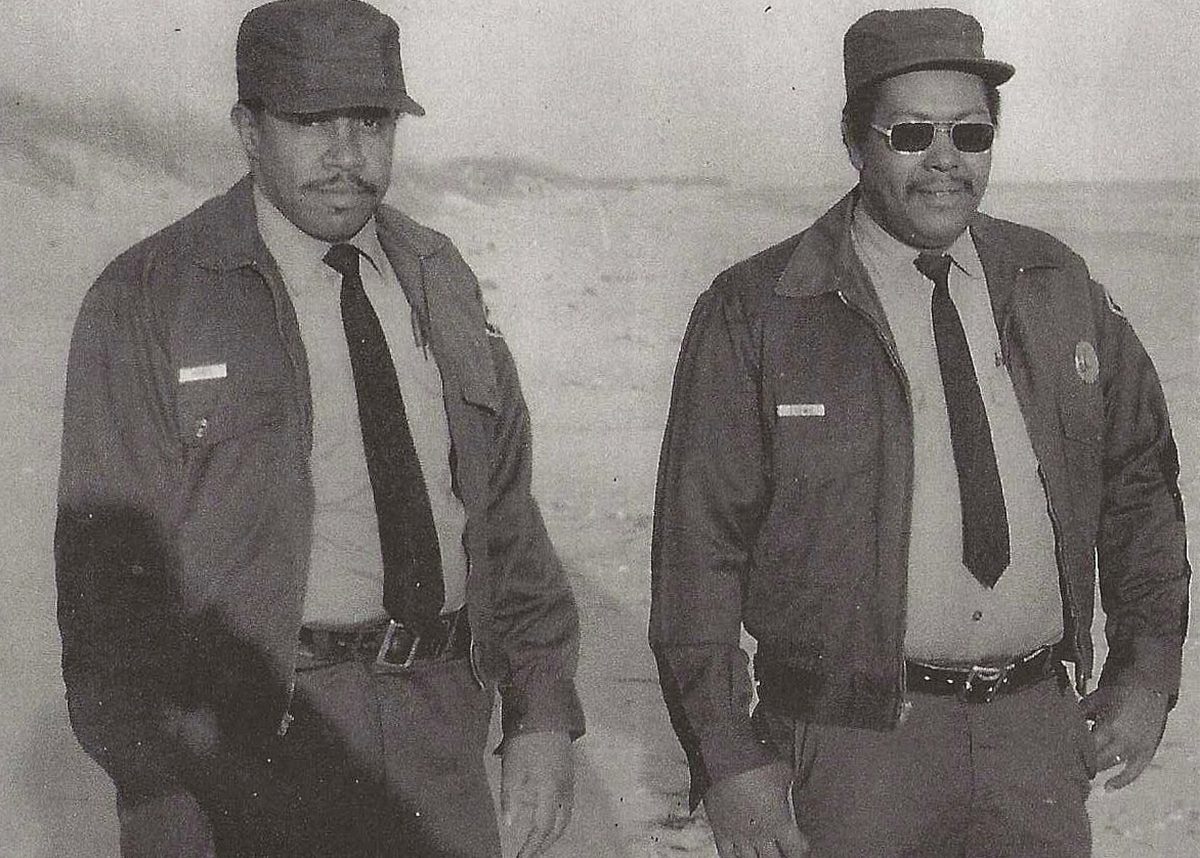

Understaffed and underfunded, Crews and Ranger Jesse Hines, along with some seasonal help, somehow managed to always get the work done. If an engine on the ferry broke down, they had to fix it. They prided themselves in switching out motors in under an hour, keeping the ferries on time. As a captain licensed by the U.S. Coast Guard, Crews piloted the ferries when seasonal captains were unavailable – an issue attributed to the low pay.

With files and a clipboard in hand, Crews also took on the administrative work while on the boat during the 10 minutes of down time between trips while at the dock.

For decades, the North Carolina State Park system struggled with woefully inadequate budget appropriations. Specialty positions such as resource management and educational interpretation were pie-in-the-sky aspirations. A ranger had to have the interest and desire to initiate these duties on their own.

One summer morning Superintendent Crews got word that a nesting loggerhead sea turtle was flipped over on its back and unable to return to the ocean. The turtle was rescued and this awareness led to one of the longest research programs documenting sea turtle nesting in the state.

In 1981, Crews was promoted to a senior level superintendent position at Cliffs of the Neuse State Park near Goldsboro. Leaving Hammocks Beach, he took the same leadership skills to “The Cliffs,” managing it for 16 years before retiring in 1997.

In retirement, Crews didn’t just kick up his heels and sit around drinking iced tea on the porch. He continued serving his community as he had been doing for decades while working at Hammocks Beach and Cliffs of the Neuse.

More than 40 years ago, Crews, who has a deep interest in youth sports, became a charter member of the Swansboro Century Club, which supports school athletics. He was a fixture at hundreds of high school and middle school football and basketball games, keeping a steady hand on the clock as the timekeeper and official scorekeeper.

For close to 20 years, he worked as a district coordinator with Onslow County Parks and Recreation, organizing and managing youth basketball programs. In 2021, the school system honored Crews for his contributions to the community by naming Swansboro’s middle school gymnasium the “Claude E. Crews Annex Gymnasium.” In a newspaper article recounting the event, words like “role model, dependable, selfless, dedicated, respected and friend” were used to describe his commitment to public service.

Crews continues to support the park where he started his career, serving as treasurer, board member and member of the park support group, the Friends of the Hammocks and Bear Island.

I, too, eventually became the superintendent at Hammocks Beach State Park, my dream job. During my years at the park, I was frequently asked about Crews by park visitors who remembered him from his time at the park.

“Where is Superintendent Crews?” they would ask with a smile on their faces.

These included his old friends wanting to catch up and say hello and some people just wanting to tell me a story about his kindness. Parents showed up with their children, hoping to introducing them to Superintendent Crews. A true ambassador of North Carolina State Parks, people still ask about Crews today.

Recently, Crews was honored by the North Carolina Coastal Federation with a Pelican Award for “Leadership and Dedication to Coastal Protection, Recreation, and Cultural Resources,” a well-deserved honor to recognize his contributions to our coastal heritage.

There is a Bob Dylan song where he sings in search of dignity. “Searching high, searching low, Searching everywhere I know.” Finally, he sings, “Have you seen Dignity?”

Dylan may not have found dignity, but I can point him in the right direction. Claude Crews, a man of character, dignity and grace, a person whom we would all do well to emulate.