Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

Last week, the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in a suit brought by Chemours. The chemical company, which manufactures GenX (HFPO-DA), a class of a per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, at its Fayetteville Works facility, challenged the health advisory established by the agency in 2022 for GenX in groundwater.

Supporter Spotlight

Chemours claimed the EPA set the advisory level too low — at 10 parts per trillion — and relied on faulty research to establish it. However, the three-judge panel ruled that the advisory was not a federal regulation and, therefore, rejected Chemours’ argument the EPA acted unlawfully when issuing a health advisory about the exposure risks of GenX in drinking water.

“Through the years, our community has learned that when companies like Chemours are not actively hiding the science, they are usually attacking it,” said Emily Donovan, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear. “This is a win for public health and every resident harmed by GenX exposures. The courts got it right this time.”

In April 2024, the EPA established maximum contaminant levels for six PFAS in drinking water, out of the thousands of PFAS manufactured in the U.S.

The court’s ruling means a consent order, established in 2019 between Chemours, Cape Fear River Watch, and the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, will remain intact — at least for now. Chemours vows to mount more court challenges.

Under the consent order, Chemours is required to carry out specific tasks, such as drinking water well testing, for people who live near the site, including in New Hanover, Brunswick, Pender and Columbus counties.

Supporter Spotlight

That includes extending testing to one-quarter mile beyond the closest well with PFAS levels above 10 parts per trillion and annually retesting any wells sampled. Additionally, Chemours is responsible for providing clean drinking water options, such as whole-house filtration systems, to those with wells contaminated with GenX compounds above 10 ppt.

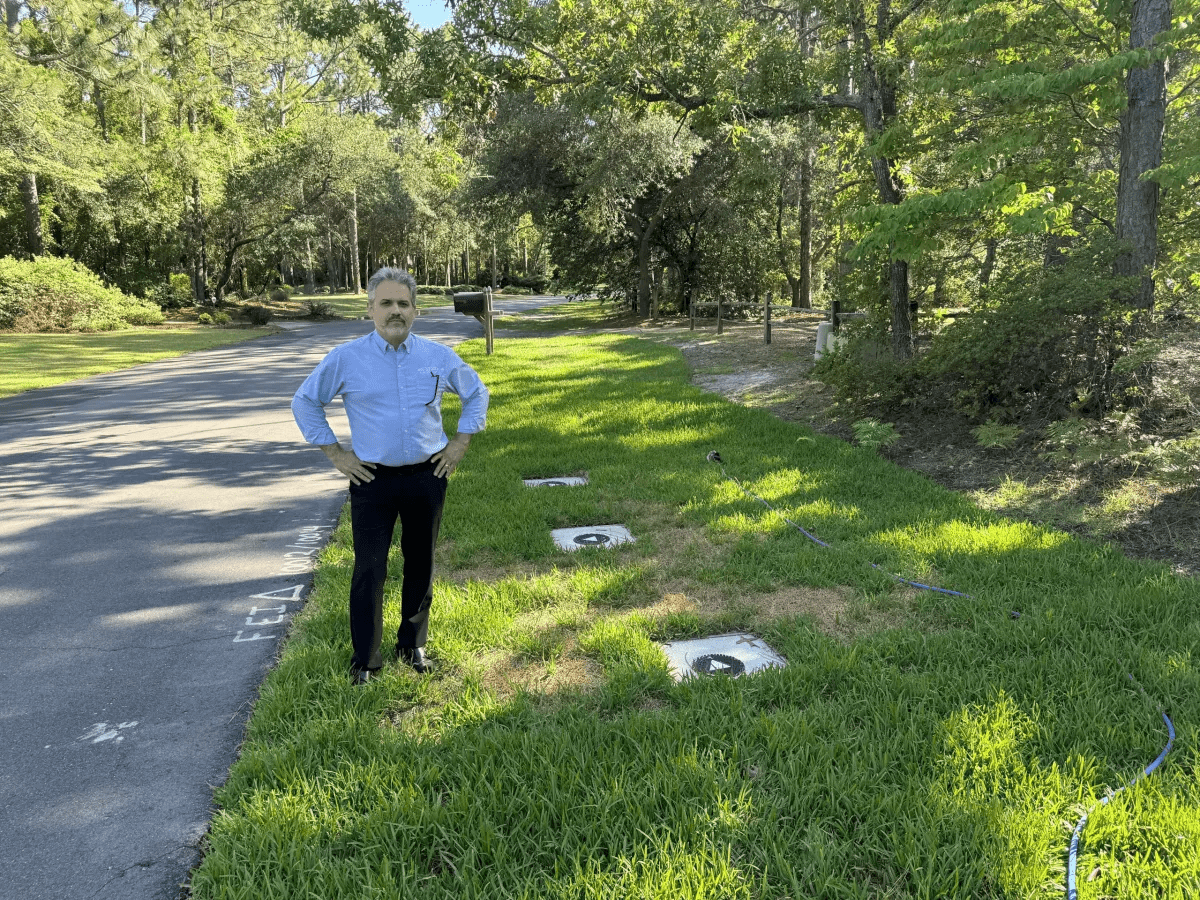

For area homeowners like Wilmington resident and business owner Steve Schnitzler, whose well’s GenX level exceeded the health advisory standard when it was tested in August 2023, the court’s ruling means Chemours must keep providing safe drinking water to his home.

“I have four reverse osmosis systems in my house right now that Chemours paid for and will maintain for the next 20 years so that we can have clean drinking water,” he said.

‘Forever chemicals’

There are roughly 15,000 unique per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS) in the environment, according to experts. Because of their persistence in the environment, PFAS are commonly referred to as “forever chemicals.” They are present in multiple products, including cosmetics and apparel, microwave popcorn wrappers, dental floss, firefighting turnout gear and some firefighting foams.

The chemicals are associated with such adverse health effects as increased cholesterol levels, kidney and testicular cancer, dangerously high blood pressure in pregnant women and decreased vaccine response in children.

The two most extensively produced and studied families of compounds, PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid), have been phased out in the U.S. Still, because they don’t break down quickly, they can keep accumulating in the environment and in the human body. GenX or HFPO-DA (hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid) was created as a replacement for PFOA.

PFAS Glossary

PFOA – Perfluorooctanoic acid, also known as C8, is produced and used as an industrial surfactant, which helps things not to stick to one another in chemical processes. It also is a raw material for other forms of PFAS. PFOA was widely manufactured but has largely been phased out of production.

PFOS – Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid was a key ingredient in Scotchgard before being banned by the European Union and Canada. Several U.S. states have banned the chemical, derivatives of which were also used in cosmetics. The EPA announced in 2021 that it would regulate the presence of PFOS in drinking water.

GenX – is a derivative salt of hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) and was manufactured by Chemours. It’s the substance initially found contaminating the Cape Fear River in 2017. GenX has been used widely in food wrappings, paints, cleaning products, nonstick coatings and some firefighting foams.

A win for now?

Chemours plans to continue to press its case against the EPA’s position on forever chemicals and will next look to present arguments in a Washington, D.C., appeals court, according to Reuters.

Looming in the background of the legal battle between Chemours and the EPA is the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo. The court ruled that federal agencies such as the EPA would no longer have the authority to use their expertise to interpret ambiguous laws. Instead, judges will assume responsibility for doing so.

The ruling affects the so-called Chevron Doctrine, which emerged from a 1984 Supreme Court case between Chevron Corp. and the Natural Resources Defense Council. The court ruled to defer to the experts at regulatory agencies when federal regulations were ambiguous, so long as the regulators provided a reasonable interpretation.

Could the Supreme Court’s ruling handicap regulators and tip the scales and favor corporations such as Chemours in future cases?

“The repeal of Chevron deference can cut both ways,” said Tom Fox, senior legislative counsel for the Oakland, California-based Center of Environmental Health.

“After all, Chevron v. [Natural Resources Defense Counsel] in 1984 was a case brought by NRDC challenging the Reagan administration’s deregulatory actions under the Clean Air Act.” Fox said. “It could be argued that Loper Bright may make it easier to challenge deregulatory actions. It also could be argued that the court’s decision did not affect deference to agency scientific judgments. However, we have seen numerous examples of the Roberts court (and lower court judges) ignoring and/or cherry-picking facts, science and history.”

When asked what environmental groups and their supporters can do to prepare for a possible shifting legal landscape, Fox said to do their homework and stay vigilant.

“I would advise public interest organizations to be strategic in bringing cases in appropriate judicial districts,” he said. “In addition, the Loper Bright decision highlights the importance of science and community involvement in agency rulemakings.”

As a business owner, Schnitzler posed a question for those who place business interests above public health.

“This general ‘business can do no wrong, and we have to keep allowing [corporations] to do horrible things because otherwise we’ll stifle innovation and will stifle growth,’ at what cost?” he asked.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.