North Carolina environmental organizations are celebrating a recent decision in a coastal North Carolina man’s challenge to remaining federal wetland protections under the Clean Water Act.

The case is ongoing.

Supporter Spotlight

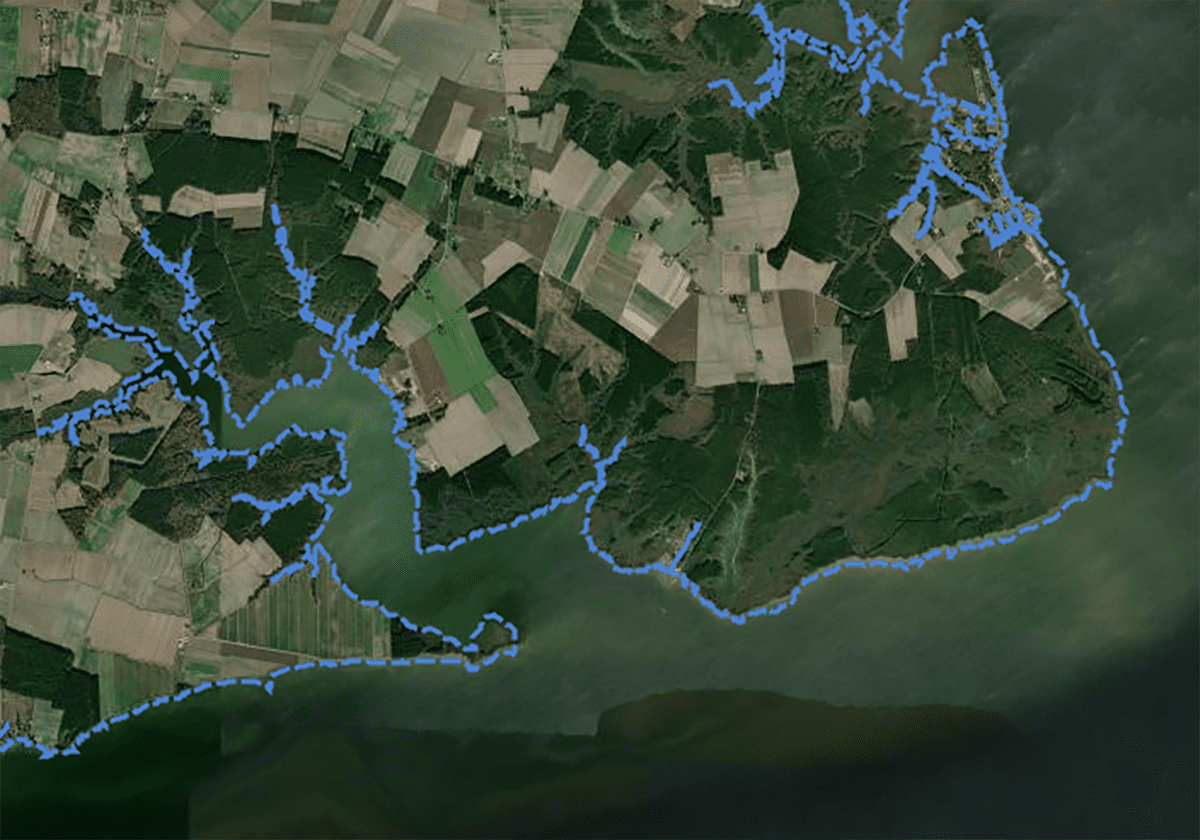

Robert White of Pasquotank County, who operates various businesses in area, brought the case in March, challenging what he contends are illegal provisions in Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers rulings and seeking “to restore his own right to make use of his own land.” White seeks to operate a sand mine adjacent to Big Flatty Creek and near the Pasquotank River.

The Southern Environmental Law Center intervened in the case on behalf of the National Wildlife Federation and the North Carolina Wildlife Federation. Those nonprofit groups say White seeks to virtually eliminate federal protection of wetlands, after the U.S. Supreme Court nearly gutted existing protections last year in its Sackett v. EPA decision.

In January 2023, the EPA brought a civil enforcement action against White after he allegedly discharged pollutants into jurisdictional waters without a permit when he built and filled bulkheads in open water and wetlands, both marsh and forested, at his parcels on the Pasquotank River and Big Flatty Creek. This enforcement action is ongoing. Last fall, White asked the court to stay an enforcement action pending against him. When that failed, White turned from defense to offense, as Boyle noted in his ruling.

White in April asked the court to preliminary enjoin federal agencies from enforcing Clean Water Act regulations as they pertain to him and his properties.

Related: Wildlife groups seek to intervene in Pasquotank man’s case

Supporter Spotlight

But Judge Terrence W. Boyle on June 17 issued a scathing decision for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina denying White’s motion for a preliminary injunction.

“White has failed to show that he is likely to succeed on the merits of either of his claims,” Boyle ruled.

“We are disappointed with the court’s ruling,” said Paige Gilliard, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, which is representing White in the case . “The Supreme Court was clear in Sackett that federal jurisdiction over wetlands requires both a continuous surface connection and indistinguishability from jurisdictional waters. The CWA regulates navigable waters, not land, so indistinguishability is a critical part of the Sackett test. The Amended Rule’s lip service to continuous surface connection is not enough under Sackett.”

The Pacific Legal Foundation represents challengers to environmental laws free of charge and “defends Americans’ liberties when threatened by government overreach and abuse,” according to its website.

White had alleged that the “adjacent” wetlands provision in the new federal rule is inconsistent with the Sackett test for jurisdiction over wetlands. He asked the court to find the new rule unlawful and set it aside as “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion.” White contended for those same reasons that the new regulations exceeded the agencies’ statutory authority and must be set aside.

Boyle ruled that White failed to show that he was likely to suffer irreparable harm without a preliminary injunction, “that the balance of the equities tip in his favor; and that an injunction would be in the public interest. Boyle called that failure “fatal to his motion.”

Boyle ruled that “White’s challenge to the waters of the United States, or WOTUS, rule that resulted from the Sackett decision, “smacks up against the Rule’s fidelity to ‘waters of the United States’ and Sackett’s test to determine when an adjacent wetland meets that definition.”

White faltered, Boyle ruled, by isolating a phrase in the Sackett decision “from its logical connection to the remainder of the opinion.” Boyle referenced the words of former Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., applying his “familiar admonition to a different context: White is thinking words not things. The thing that makes a wetland practically indistinguishable from an adjacent ‘water of the United States’ is the presence of a continuous surface connection. Thus, the Amended Rule faithfully conforms to the definition of ‘waters of the United States’ as interpreted by Sackett.”

Michael and Chantell Sackett, the people behind the case name, had purchased property in Idaho and began backfilling their lot so they could build a house. The EPA informed the Sacketts that their property included wetlands and they needed a permit because they were discharging pollutants into “waters of the United States.” The Sacketts sued, and after nearly 15 years their case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, where they prevailed.

In its 5-4 decision, the nation’s highest court ruled that “waters of the United States,” pertains to only wetlands that have “continuous surface connection.”

Advocates said the revised rule leaves water quality in North Carolina unprotected and increases the chance of flooding.

The North Carolina League of Conservation Voters said in May that White’s case “could finish killing off federal rules protecting wetlands.”