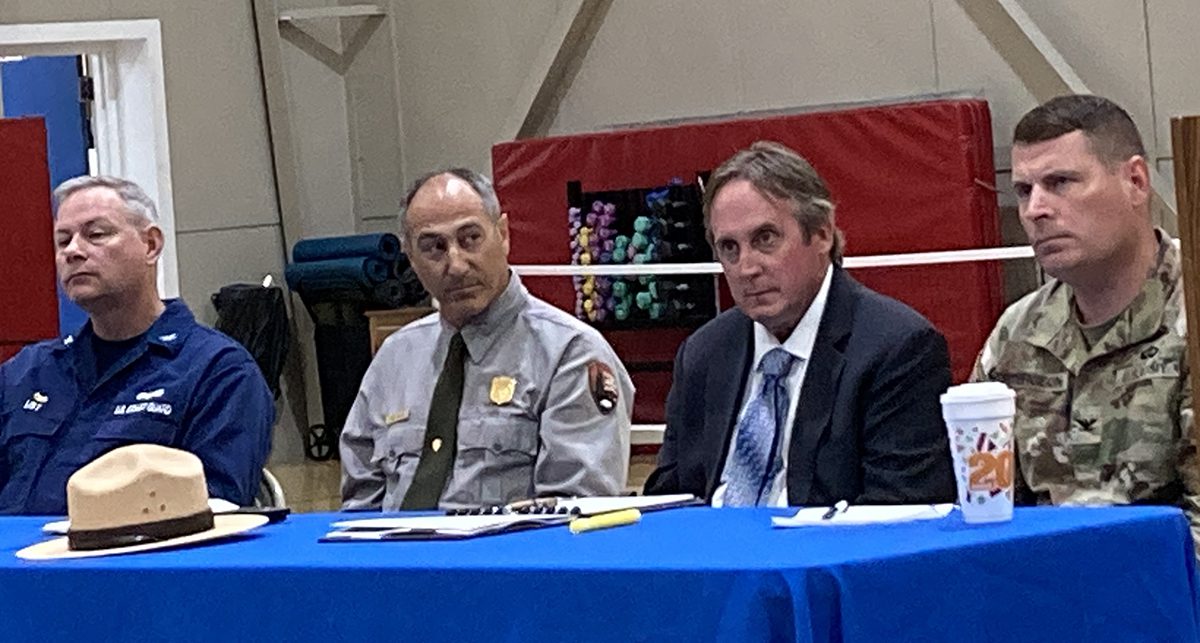

BUXTON — Two Army Corps of Engineers officials who oversee environmental pollution cleanup at a former Navy base at Cape Hatteras met Tuesday evening with area residents to address their frustration about intermittent petroleum odors and exposed infrastructure debris on the eroded beach near the site.

“Sometimes you see things there, and a day later they’re covered up,” Col. Ronald Sturgeon, the Corps’ Savannah District commander, told attendees at Dare County’s Fessenden Center. “It is certainly a complex site, a very unique situation down here.”

Supporter Spotlight

As part of Sturgeon’s duties with the Corps, he is in charge of the Savannah District’s Formerly Used Defense Site, or FUDS, program in the Southeast that has previously removed storage tanks and 4,000 tons of petroleum-contaminated soil at the former submarine survey operation in Buxton, as well as groundwater remediation and continued monitoring. The Corps was designated in 1991 to take responsibility for environmental restoration of the site.

Although the area is part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore — the landowner — the debris and apparent contamination are remnants of two military bases that operated from 1956 to 2010, first by the Navy and then the Coast Guard. Increasingly severe coastal erosion has unburied remains of base structures, including septic systems and pipes sticking out of dunes where there’s been escarpment.

Since a series of late summer storms, there have been periodic reports from the public of a strong diesel smell at Buxton Beach, as well as evidence of petroleum-contaminated soil, an oily sheen on the nearshore ocean waters, and expanding amounts of concrete, rebar and pipes exposed on the shoreline. In September, the National Park Service closed 0.3 miles of beach near the end of Old Lighthouse Road.

Sturgeon said a FUDS team has come to the site repeatedly since September. Most recently on Monday, May 13, when contractors removed a suspect pipe from the beach and collected samples from surrounding soil. Results were expected within 10 days.

If the sampling shows contamination, he said, additional funds will be requested.

Supporter Spotlight

Glenn Marks, chief of reimbursable programs and project management at the Corps’ Savannah District, said about 70 to 80 feet of pipe was removed as part of the $525,000 project.

When asked by an attendee about who “the onus falls on” to remove from the beach the chunks of foundation and other remains of the Navy base, Sturgeon said that the FUDS regulation does not provide the authority or funding.

“If there is not environmental hazards out there, how are we as a collective group going to take care of this?” he responded. “The U.S. Corps of Engineers has never received direct funding for that. The (Corps) would have a hand in that if funding was provided by the landowners.”

According to the National Park Service, its permit issued to the Navy in 1956 required that all structures, including foundations, be removed and that the 50-acre site would be cleaned up when the Navy ceased operations in 1982. In addition, its 1991 agreement with the Coast Guard, the agency said, obligated the Coast Guard to remove structures, restore the landscape, conduct a hazardous materials survey and take responsibility for any necessary mitigation and/or cleanup. Coast Guard Group Cape Hatteras was operating in Buxton from 1984 through 2010, when the base relocated to Fort Macon.

But as far as current cleanup obligations and responsibilities, details about who, what and when have become a bureaucratic muddle. There are also the complications created by the remove of decades and quickly changing conditions from rising sea levels and increased coastal erosion.

The Coast Guard and the Corps, however, have worked closely with Cape Hatteras National Seashore officials to resolve the issues and determine appropriate funding and authorization options, said Superintendent David Hallac.

“We are looking forward to a complete remediation of this site,” he told the community members. “I am proud we have good partners.”

Even though all three parties are part of the federal government, each bumps up against the other’s rigid regulatory strictures, tight budgets and staff shortages, and legal fuzziness. The old Navy base, for instance, is no longer part of the Navy, but its cleanup is still managed under the Department of Defense, and it is now the Corps’ FUDS baby.

The Coast Guard, however, while military-adjacent, is part of the Department of Homeland Security, not the Defense Department. And the National Park Service is part of the U.S. Department of the Interior, a huge federal agency with management concerns centered on conservation of natural resources and recreational areas, such as Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

To complicate matters further, Hallac said some Coast Guard structures are actually on top of Navy building foundations.

“I think the most important thing is we’re not going to stop working till we get all this debris off the beach,” he said. “The take-home message is there’s a lot of debris under the sand and it all has to be removed.”

Related: Park Service urges public to avoid debris on Rodanthe beach

The Coast Guard had completed an environmental site assessment in 2008 and a soil assessment for the onsite wastewater facility in 2010, according to the National Park Service.

Although polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, metals, pesticides and other contaminants above acceptable Environmental Protection Agency standards were found in the soil, remediation through the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation, and Liabilities Act, or CERCLA, process was not done at the two affected drain fields, according to the Park Service said.

In 2021, Hallac reached out to the Coast Guard, which restarted the survey work, taking numerous water and soil samples across 32 acres at the site, said Joseph Lambert, an environmental engineer with the Coast Guard’s Cleveland Engineering Unit, during a brief interview after the meeting. A report on the findings is currently being reviewed and is expected to be finalized this summer.

Coast Guard Sector North Carolina Capt. Timothy List, who also participated in Tuesday’s information session, said that the scope of contamination is not yet clearly defined, but that the Coast Guard intends to do its part, while also working with its partners, to clean up the site.

“We’re here to continue for the long haul,” he told attendees.

It remains unclear why the cleanup and removal work required under the Navy and Coast Guard permits was not completed.

Marks said that his understanding is that the Navy permit is expired, although he didn’t explain what effect that would have on the conditions that had been stipulated.

“I cannot speak for what the Navy signed up for or did not sign up for,” he said.

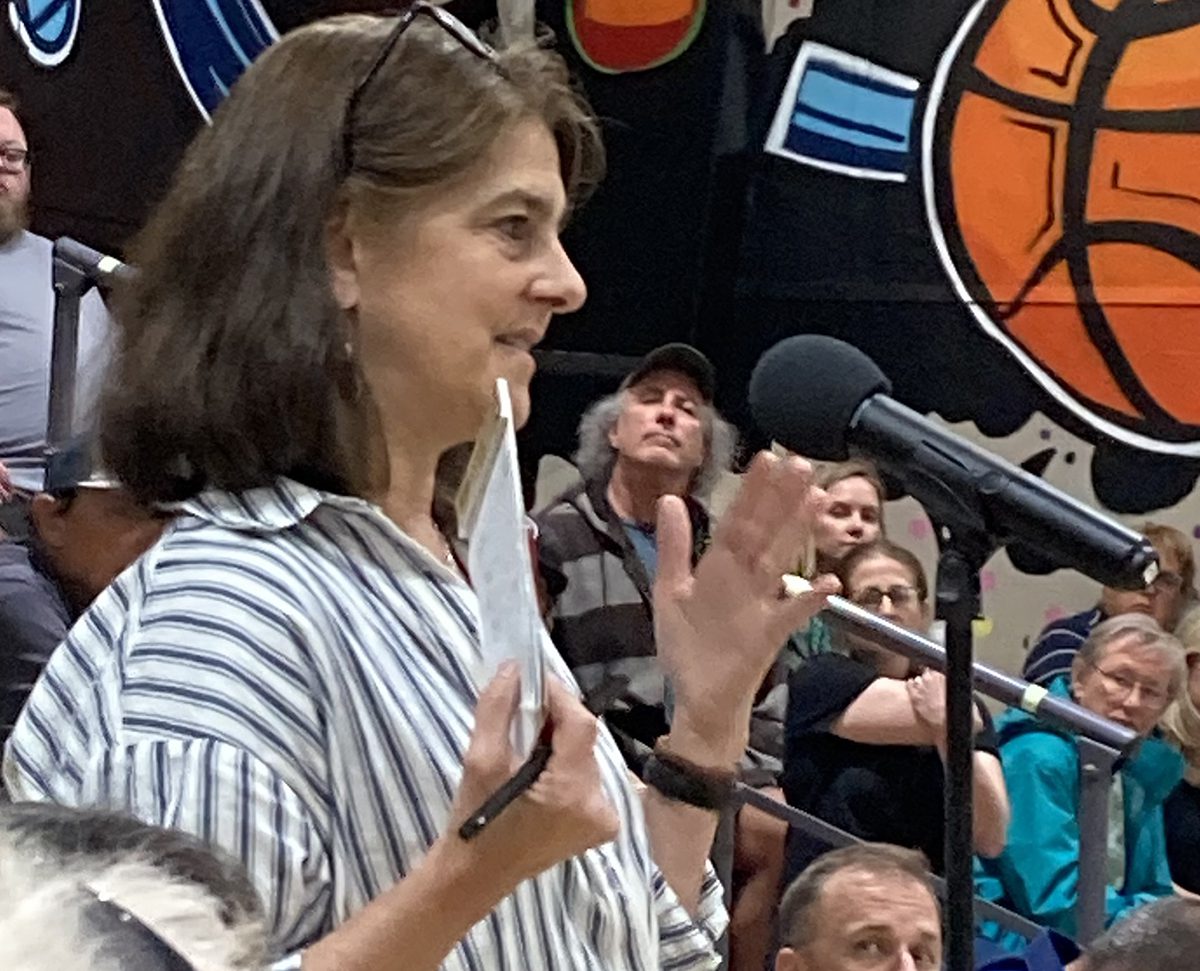

Julie Youngman, senior attorney with Southern Environmental Law Center, noted during the public comment portion of the meeting that any similar pollution or debris sullying a more prominent national park such as Yellowstone “wouldn’t be there a week.”

Referring to a provision in the Department of Defense manual, “Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) Management,” Youngman asked the Corps’ representatives whether they had asked their bosses about trying to qualify the unique Cape Hatteras situation for special consideration.

According to the “Petition for Eligibility” on page 18 of the manual, “… in exceptional cases, a DoD Component may petition the … Environmental Management Directorate … for clarification or approval to consider a specific activity as an eligible environmental restoration activity.”

Responded Marks: “I’ll commit to looking into it and having me and the lawyers look into it and see if that holds water.”

In an April 30 letter from Kyle Lewis, an environmental attorney for the Corps’ Savannah District, answering an inquiry from Youngman and North Carolina Coastal Federation Executive Director Braxton Davis said that the Corps’ authority to remove the “remnant” and unsafe structures is limited to what existed at the time the Navy left the site.

“The infrastructure that is currently being exposed by erosion was sound when transferred out of DoD control in 1982; therefore such structures are not eligible to be addressed under the FUDS Program,” Lewis wrote.

The state Department of Environmental Quality and Dare County Department of Health and Human Services also have been working with the agency partners to urge action on the cleanup and to keep the public informed.

Meanwhile, as residents reminded the officials, whether because of regulatory or funding constraints, the public beach in their community — a favorite spot to surf and swim and stroll at Cape Hatteras National Seashore — is still littered with ugly and dangerous chunks of concrete and rebar and stinks of diesel, and it’s all because of the infrastructure and contaminants that the Navy and the Coast Guard left behind.

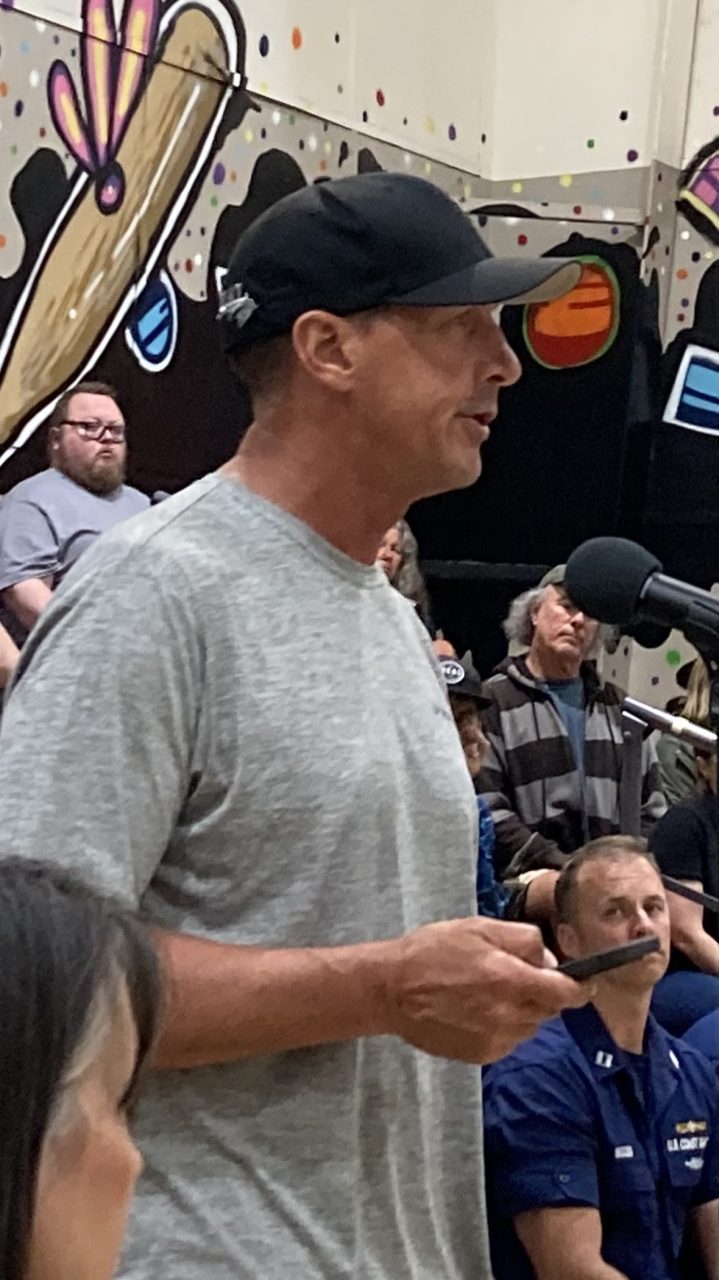

One man named Michael who owns a vacation house near the closed beach lamented that his rental income is now “nonexistent.”

“So we can’t rent the house, we can’t sell the house, we can’t live in the house,” he said.

Trip Forman, co-founder of REAL Watersports in Waves on Hatteras Island, said during the public comment period that the negative message about the situation has become a blight on tourism.

“Something needs to be done to resolve this,” Forman said “There’s a lot of cancellations. There’s a lot of negative press. It’s spinning out of control.”

The Corps will establish a restoration advisory board, a public forum for sharing information with the community, for the Buxton site within a year, Marks, with the Corps, said.

Dare County officials also promised to stay involved and keep the public informed about the situation.

“We’re committed to see this through,” said Dare County Board of Commissioners Chair Bob Woodard.