Since 2013 Steve and Sally Gudas have been organizing and hosting a Flat Top Cottage tour in Southern Shores, giving people a chance to see and experience, if for a brief time, an iconic part of Outer Banks architectural history.

This year, that tour was Saturday, and more than 1,000 came out — a record attendance, the Gudases said. It was 1,013 to be exact, compared to 2022, “when we had 722,” Sally Gudas told Coastal Review Wednesday.

Sponsor Spotlight

Built over a 15-year span beginning in the late 1940s, the houses were simple structures. Designed for a summer vacation, the homes were concrete block construction. There was no foundation really, just a concrete floor on sand. And there was no insulation.

“When, we come in here when it’s cold, it takes one full day to get it warm, including the fireplace. Thank God for that,” Steve Gudas said Sunday, having been too busy to chat during the tour.

The houses were designed by Frank Stick, an artist, real estate developer and, to many, a visionary with a knack for self-promotion. In 1946, Stick had just purchased the 2,600 acres that now comprise Southern Shores, and he had the idea that to sell each lot and home for one flat price.

But to do that, he needed something that was easy to build and used as much locally sourced material as he could get his hands on. The sand came from Outer Banks beaches, until the federal government made that illegal in 1955. The structural beams, the cabinets — any interior wood — were all juniper, which at the time was readily available and the cheapest wood to be had.

Frank Stick also, as his son, David, wrote, “… introduced a completely new cottage style for the Outer Banks … What he came up with was flat-top structures of varying sizes and shapes, using concrete blocks as the primary building material.”

Sponsor Spotlight

Related: Frank Stick finds success, designs signature Banks cottage

Tours of the homes were held this past weekend and revealed just how varied the flat-top design could be, and how the structures – each uniquely named – evolved over the decades.

Sea Breezes, built in 1956, was originally a duplex, but the common wall was removed some time after it was built, and a sliding pocket wall was put into place. This modification allowed the house to be used as either two, two-bedroom cottages or a single, four-bedroom home.

Pink Perfection, built in 1952, is a rambling four-bedroom Flat Top. Unlike almost all of other Flat Tops, it was neither designed nor built by Frank Stick.

Aside from the obvious design element, there are among the Flat Tops several similarities. Among them, in almost every house, the original juniper beams and trim have been retained. Outside, almost all have wide soffits.

Very few are still in the original owners’ hands. Ashbel Falconer is an exception. The Falconer Cottage his parents purchased in 1955 when he was 4 is situated on a side street, atop a low rise that, at one time, had an unobstructed view of the ocean. Not anymore. Live oaks and other houses block that view now.

“The only thing that was here was sea oats and sand spurs,” Falconer told Coastal Review recently. “It was all sand.”

The tidy homes are a labor of love for the owners, as Falconer noted with a laugh.

“They are maintenance hogs.”

Steve Gudas shares that sentiment. “When you own it, you’re just invested in it,” he said.

Preserving a legacy

Matt Neal, owner of Neal Contracting of Kitty Hawk, has been in love with Flat Tops since his family lived in one when he was a child.

“In the late ’80s, early ’90s, we lived in one for a period of time in Kill Devil Hills, and so it’s always been a childhood memory of mine,” Neal said recently.

He now owns a Flat Top built in the 1950s in Southern Shores, although he describes it as “full-flat roof — a low, sloped, single shed-style roof.”

His experience in restoring reflected the challenges other owners know from simply maintaining one. “It’s a challenge,” Neal said.

“It was fun in a way,” he said.

“I would take juniper out of the interior closets and use it to refurbish the cabinets. And I had to take the juniper off the wall in the bathroom to update the wiring and then put it back,” Neal explained. “That house had a slab (floor) that had no vapor barrier. We were able to get the old linoleum up, put a vapor barrier on top of the slab (and) put cork flooring down and keep … original doors and hardware. And it still has the original windows.”

The homes are also vanishing. While unclear how many there were originally, some estimate as many as 300, Sally Gudas told Coastal Review that number seems high.

“I don’t think it’s 300,” she said. “I’ve been asked that question. I just really don’t know. But I am working on it.”

She has a reasonable guess as to how many are still standing in Southern Shores.

“I think we’ve identified 25,” she said.

There are attempts to preserve the structures. The town of Southern Shores created a Historic Landmarks Commission that evaluates homes more than 50 years old. If a house meets the criteria, property owners get a reduction in their town property tax.

To date, there have been five Flat Tops added to the program, although additional property owners have submitted applications.

Tax incentives alone, however, are not enough to save the buildings. With property values in the millions along the oceanfront, the economics of preservation may not add up when a property is passed to two or three sibling heirs.

There is increasing concern that the Flat Top legacy will be lost.

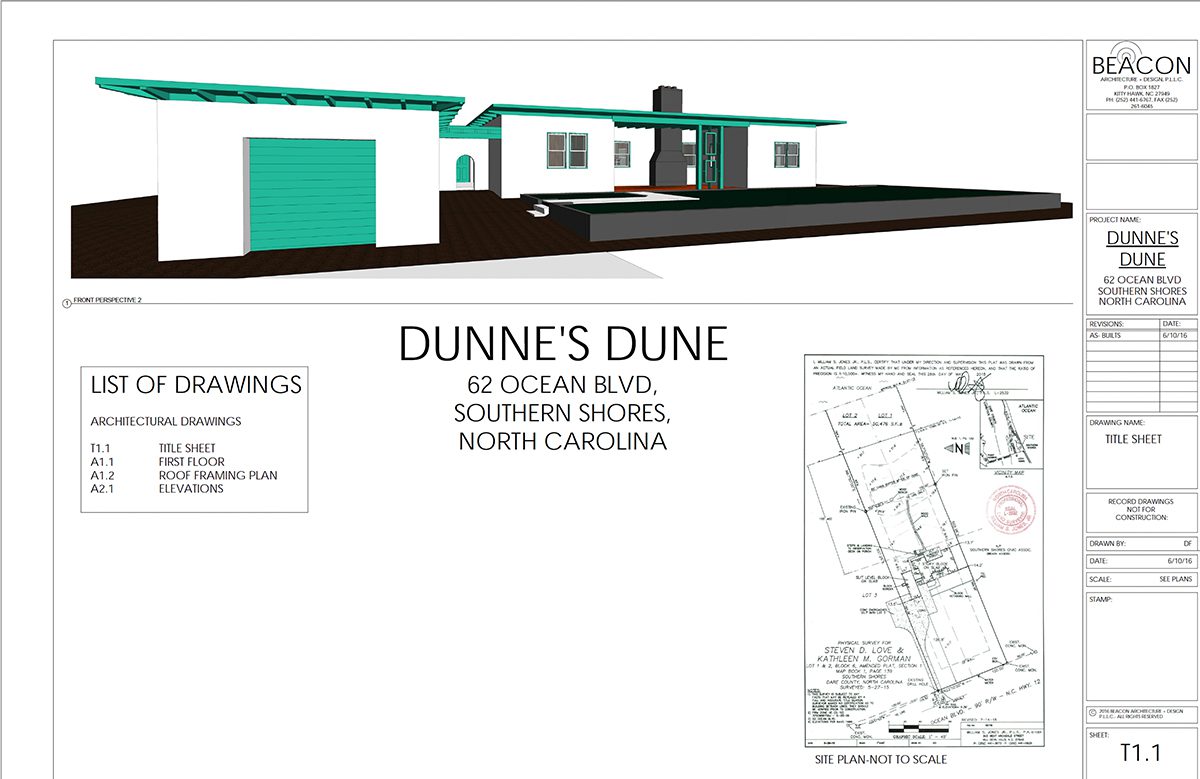

Architect Chris Nason of the Kill Devil Hills-based Beacon Architecture and Design is a Southern Shores resident who has for the past seven or eight years been documenting Flat Tops in town.

“It was just a first impulse,” he told Coastal Review. “So we’ve got this moment in time. Let’s just measure it, take pictures.”

Initially Nason wasn’t sure what he would do with his documentation, but since he began the project, it has become a historic record and teaching tool for his interns.

“It was a good learning experience for them. You can learn to take measurements on a small house. It’s a perfect learning experience,” Nason said.

As an architect, Nason would like to see as many of the houses saved as possible, but he acknowledged that it can’t always happen.

“I am both realistic and aspirational about encouraging folks to keep them,” he said. “These things don’t meet any codes. They’re oftentimes too low. They don’t meet the flood zone. There’s all sorts of reasons not to keep them, but that doesn’t mean we don’t try, and where we can’t keep it, it’s great to come back with something that is inspired by what was there,” he said.

To date, Nason has measured and created elevations for 34 homes, many of them no longer exist. He has created a website documenting his work, and is hoping more can be done with it.

“Eventually our goal is to do a book on it and put these plans in a book and do some photography with it. That’s still in the works,” he said.

Neal, in addition to restoring the home he owns, is also working to preserve the legacy and has built three homes based on the Flat Top design.

He characterizes the concept as Usonian, which is a Frank Lloyd Wright term to describe a single-story, flat-roofed home with wide eaves using as many locally sourced building materials as possible.

Building a home for the 21st century meant taking the original concept and bringing it to modern standards and efficiency.

“It’s always astonishing to me what people were willing to accept back then, but they’re not willing to accept it this time,” he said. “But it works. I’s very functional and very utilitarian. It’s a throwback to the quietness in sort of a more out-there living of the Outer Banks.”

Post has been updated.