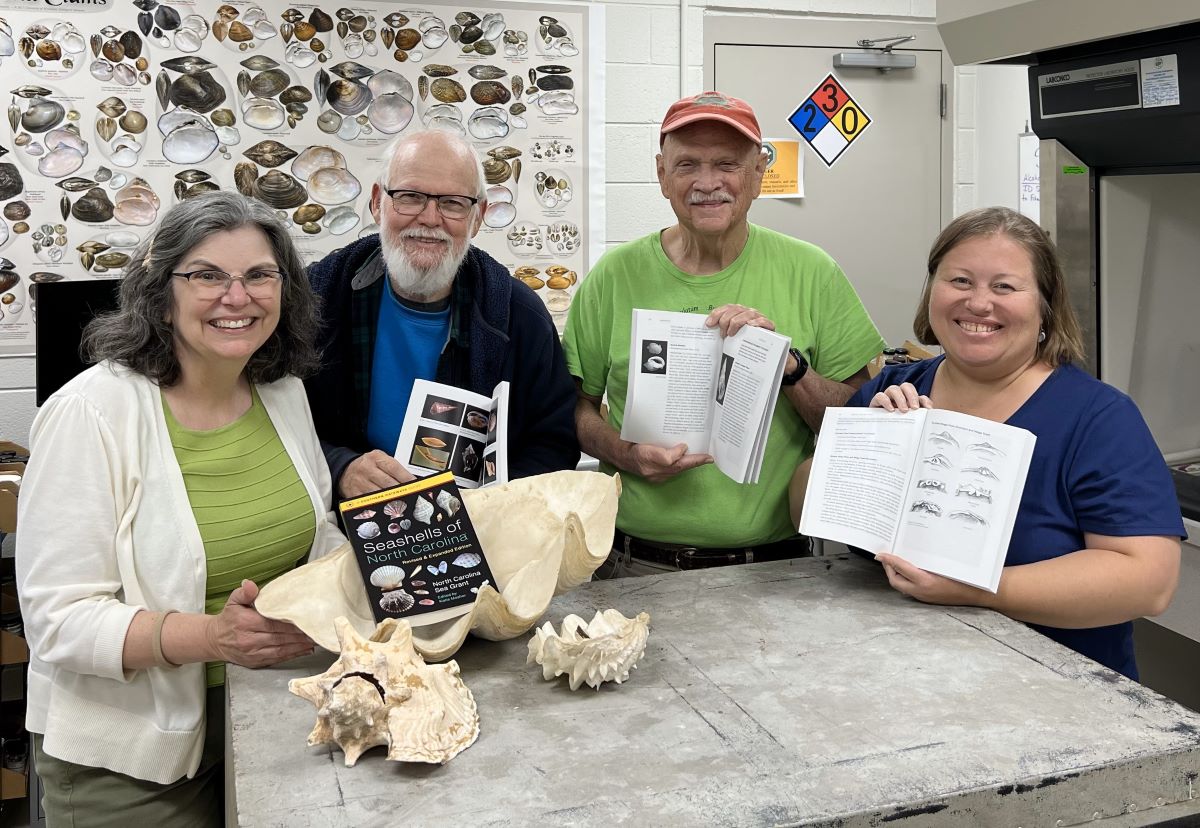

North Carolina Sea Grant has revised and expanded its “Seashells of North Carolina,” a long-trusted guide to help everyone from beachcombers to graduate students identify the treasures they find along the Tar Heel State’s beaches.

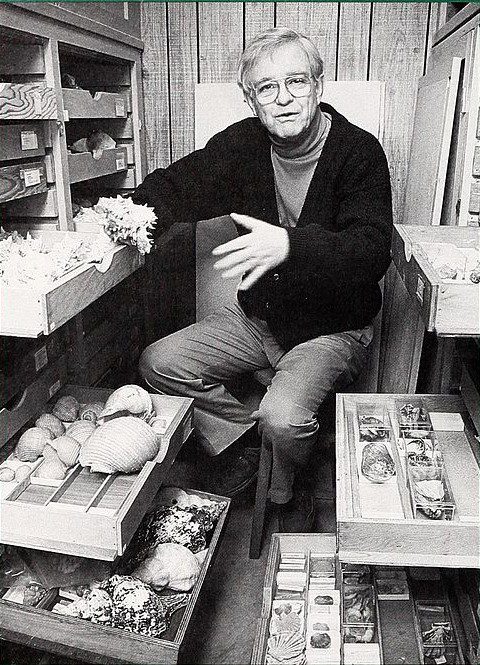

The late Hugh Porter, who was referred to as “Mr. Seashell” during his nearly 55-year career at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, and Lynn Houser wrote the guide that was originally released in 1997, was edited by Jeannie Faris Norris, and features images captured by Beaufort-based photographer Scott Taylor.

Supporter Spotlight

The revised and expanded edition published in June builds on the original and includes detailed descriptions and photos of 275 species, instructions for shell identification, introductions to the biology and geographical range of these animals, and an index of scientific and common names with updated scientific terminology, per the publisher, University of North Carolina Press.

Porter, who died at 86 in 2014 in Carteret County, began his career at UNC-IMS in the 1950s as a research assistant, then served as an instructor in 1957 and just a few years later, in 1963, became an assistant professor. He retired in 1996 but was a regular fixture through 2010, according to Sea Grant.

Porter started the shell collection in 1956 that was on display at UNC-IMS during his tenure. In the late 1990s, the specimens totaling more than 233,000 were donated to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh to become part of the mollusks collection there. The collection is under the care of Research Curator Art Bogan, who is also on the team that updated the book.

Bogan, who said he primarily works with freshwater bivalves, joined the museum in 1997, when there was but a small shell collection at the museum. He learned shortly after moving into the role that UNC-IMS had donated its fish collection and Porter’s shell collection to the museum, and Bogan spent several years cataloging the thousands of specimens.

For the last 300 years, what everybody’s been using for identification is the shape, the sculpture, the color, the size to arrive at identifications, but within the last probably 25-plus years, with the advent of genetics and genomics, identifying shells has “gotten messy,” Bogan said. Researchers are going deeper by looking at comparative anatomy and dissecting the animals to see “how the plumbing all fits together” or how the organs are arranged.

Supporter Spotlight

Bogan, who has an obvious passion for mollusks, said that the great thing about malacology, or the study of mollusks, “is you can learn something new every day. It is changing. There are new discoveries, new species described, new resources becoming available.”

Katie Mosher, who retired earlier this year from her position as North Carolina Sea Grant’s communications director, said she started the research organization in 1998, about a year after Porter’s “Seashells of North Carolina” was published.

When she joined Sea Grant, she would witness firsthand how people could be drawn to the book.

“People would come up and just talk to us about what that book has meant to them or what it meant to their family,” Mosher said, adding that they would recount stories about taking their copies to the beach, or losing it in a flood during a hurricane, or that was at a parent’s house and unable to save it after the parent’s death.

“You hear these stories of true personal attachment that people had to a book, and it really was appealing to me,” Mosher said.

“We knew how popular (the guide) was,” Mosher continued, explaining that Sea Grant reprinted the guide several times over the past three decades, working with UNC Press for the last number of years to distribute the book.

When it was time for another reprint in the fall of 2021, UNC Press pitched to Sea Grant the idea of updating the book instead of just reprinting it.

That’s a move Sea Grant was considering at the time as well, Mosher said.

UNC Press offered to manage the printing and include the edition in its Southern Gateways Guides.

Mosher told UNC Press it was a go, assembled a team of seashell enthusiasts, or conchologists, and got to work.

In addition to Bogan and Mosher, contributors include Jamie M. Smith, who works with Bogan at the museum, Shell Club members Edgar Shuller Jr. and Douglas Wolfe, and, with Sea Grant, Erika Young, Anna P. Zarkar and Carrie Clower. Georgia Minnich, who retired from the North Carolina Aquariums system, provided the illustrations, and the book includes new photos as well as Taylor’s from the 1997 edition.

Bogan explained that before Mosher called and asked him to help, he and a few members of the North Carolina Shell Club had been discussing the need to revise the guide, especially since the taxonomy of mollusks had changed significantly since the 1997 edition. The North Carolina Shell Club formed in 1957 and holds its annual show during May at the Crystal Coast Civic Center in Morehead City.

Club members had been keeping notes like scientific name changes in their personal versions of Porter’s edition, Bogan said.

“They had already been gathering some of the information that we would need to have for the update,” Mosher added.

Shuller, former Shell Club president, said that after he retired in the 1990s he joined the shell club in 2000. That’s when he really began to get interested in shells. In the time since, he’s had a 20-plus-year education in malacology, “and not at any university, actually, just getting your feet in the sand and digging around trying to learn what you can.”

Through that, Shuller said he began to understand the amount of work Porter had invested in the guide. One thing the users complained about with the 1997 edition, however, was that it was organized by shell shape rather than the accepted taxonomic order at the time.

But that was done for “a very good reason, I’ve come to appreciate.” It was organized by the shape of a shell to make it easier for users. “That was one thing we were worried about, and of course there was the issue of the outdated nomenclature,” Shuller said.

Shuller said he had been commenting to Bogan off and on over the years about the guide needing to be revamped.

“I didn’t know he was paying attention. I was quite surprised when he called me about this and the Shell Club was quite anxious to help out on this thing,” Shuller said. “I mean, we really were. We knew that the book needed some work to bring it up to date, and we were hoping to be able to get some of our ideas into the book,” Including having the new edition arranged taxonomically correct.

Mosher explained that the emphasis being on the shell shape in the previous edition had its value, but they wanted to make the guide organized for multiple uses. “As we were putting the book together, I was trying to think about it from my kind of every person perspective,” Mosher said.

Shuller said that to help with identification, “We came up with a very unique pictorial indexing system, which I think is going to be very useful in helping people locate the shells within the book. We have high hopes for that. I think people are going to really appreciate this particular edition.”

Young, Sea Grant’s coastal and marine education specialist, began with organization in 2022, after teaching at UNC Pembroke for 13 years. She said she has been collecting shells since she was a graduate student at UNC-IMS in the 1990s and was excited when Mosher brought her onboard.

Throughout her career, Young has used field guides and, she said that this updated version is “rigorous enough for a graduate student that needs specifics but it’s easy enough to flip through while you’re walking on the beach. It should very easily get you to where you need to be to find out what you’ve collected. And I just love that.”

Following the shell path

The team all came to appreciate seashells along different paths.

Shuller found his way to collecting mostly because of curiosity, he said, and was particularly drawn in after seeing the “fantastic, amazing exhibits” the Shell Club members put together for its annual show.

He and his partner decided to participate in the show the following year, “still not knowing anything about shells. We had picked up small shells along the beach and didn’t know what they were,” Shuller said in explaining why they got in touch with the shell club in the first place. It was to learn the names.

They soon began collecting shells in earnest, then invested in a microscope to which they could mount their camera and began taking closeups of the shells. “These were film cameras, of course, so we spent an entire summer taking pictures, taking them down to have them developed, coming back, doing it again, over and over again,” Shuller said, but they ended up with “some beautiful photos,” and they did well at the show that year.

Mosher grew up in Ohio and did not see the actual ocean until she was 18. She moved to North Carolina after college and “I really found myself drawn to the ocean for many reasons, as we all are.” When she began collecting shells, “I was just mostly enamored with the colors and the shapes and knowing, knowing that there a lot of them that we were collecting didn’t have the bright color.”

Young said that while at UNC-IMS, she would often consult Porter’s shell collection or Porter himself about what she found on the beach. Now she recognizes “what a treat that was” to have that connection with Porter, and fast-forward, she’s helping to work on the revision for his book.

Bogan grew up outside Seattle and became fascinated with shells when he was at the Academy of Sciences in Philadelphia. He was responsible for putting material into the collection.

“It becomes a lifestyle. How much do you want to learn? How much do you want to invest? How much time do you have?” Bogan said. “We learn from each other, we share facts, we ask questions, and the biggest question is, how do you flip that curiosity switch in students? Get them excited about seashells, about shell shape, animals?”