Sinking land areas in major coastal cities could intensify climate change-related flooding and inundation in the next 25 years, concludes a new study.

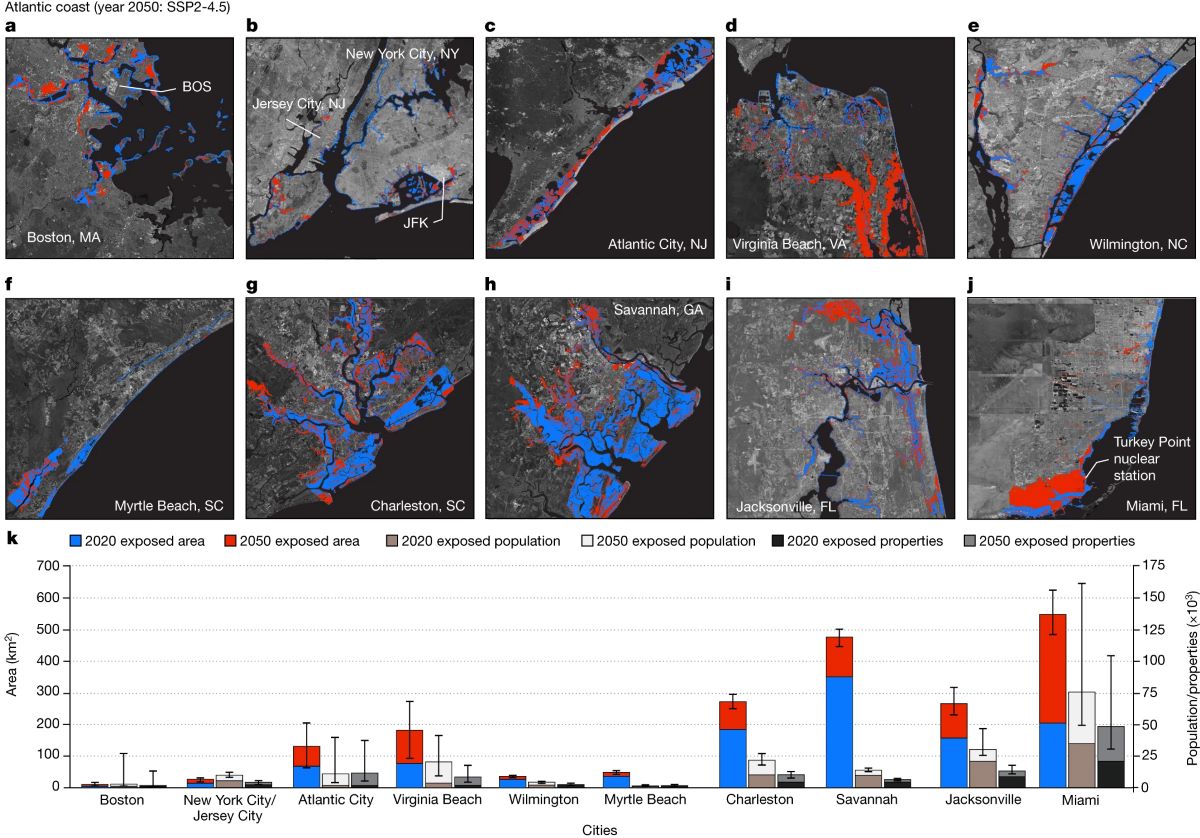

For the analysis, “Disappearing cities on US coasts” published earlier this month in Nature, the team of scientists combined data on the rising or lowering of land with sea level rise projections to calculate the potential inundated areas in 32 coastal cities, including Wilmington.

Supporter Spotlight

“As sea level rises and land subsides, the hazards associated with climate extremes (for example, hurricanes and storm surges), shoreline erosion and inundation of low-lying coastal areas grow,” which is a “factor that is often underrepresented in coastal-management policies and long-term urban planning,” the study states.

Sea levels are expected to rise about a foot by 2050. Researchers used 2020 data as a baseline to predict how much land this will cover within the next 25 years. Then, to see how much more land is projected to be exposed to flooding and inundation because of subsidence, or sinking land, high-resolution vertical land motion and elevation data was added to the sea level rise predictions.

Leonard Ohenhen, lead author of the study, told Coastal Review in an email that they found that most communities on U.S. coasts are sinking and at different rates.

“This sinking in combination with climate change-induced sea level rise poses a significant flood hazard to major communities on the US coasts, including NC. In total, a maximum additional population of 273,000 people will be exposed to flooding by 2050,” Ohenhen said. He is a graduate student in the Department of Geosciences at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia.

For North Carolina, the coastwide average rate of sinking is 1.4 millimeters, or about 0.06 inches per year, with a maximum sinking rate of 4 millimeters, or 0.16 inches, per year, Ohenhen continued. For the inundation risk, the only city researchers focused on in North Carolina was Wilmington, “and the analysis shows that an additional 2,000 to 3,000 persons, will be exposed to flooding by 2050” because of subsidence.

Supporter Spotlight

Other cities on the Atlantic Coast studied were Boston, New York City, Jersey City, Atlantic City, Virginia Beach, Wilmington, Myrtle Beach, Charleston, Savannah, Miami and Jacksonville, Florida. The study also looked at projected numbers for 11 cities on the Gulf Coast and 10 on the Pacific Coast.

Ohenhen said that on the East Coast, a total of about 300 to 370 square miles will be exposed to flooding by 2050, along with 59,000 to 262,000 people and 32,000 to 163,000 properties.

He said that natural and human processes help drive land subsidence.

“Why the land is sinking differs from location to location, and in some cases, it may be a result of multiple interlinked processes,” he continued. “For the US East Coast, sinking is driven by glacial isostatic adjustment, natural sediment compaction, and groundwater extraction.” Glacial isostatic adjustment is the ongoing movement of land reacting to being covered by glaciers during the ice age, according to the National Ocean Service.

The primary motivation for the research, Ohenhen said, stems from a growing concern over the increasing vulnerability of the country’s coastal cities to flooding risks.

“While sea-level rise (SLR) due to climate change has been a focal point of scientific studies, the exacerbating role of coastal subsidence — both natural and anthropogenic — has been underrepresented in coastal management policies and discussions,” he explained in an email.

“Recognizing this gap, our study aimed to create the first high-resolution (50 m), policy-relevant land subsidence dataset for the US coastlines and integrate this dataset with SLR projections to provide a more accurate assessment of future inundation risks.”

The reason previous flood estimates omitted land subsidence can largely be attributed to its gradual nature, “which often escapes immediate notice, leading to a lack of prioritization in flood risk models,” Ohenhen said. “While some existing projections do account for land subsidence, they typically rely on singular measurements obtained from tide gauges, which fail to capture the spatial variability inherent in subsidence rates across different regions. Our study provides the first semi-continuous spatially variable land subsidence dataset for the US coast.”

Ohenhen said there are ways to either mitigate or adapt to coastal subsidence.

“Here, identifying the drivers is important for preparedness,” he said. If subsidence is a result of glacial isostatic adjustment, “there is no way to mitigate against it, so we must adapt to the consequences,” by finding ways to elevate the land or replenish groundwater through managed aquifer recharge, which will help to reverse elevation loss.

“However, in cases where the land elevation loss is driven by the extraction of groundwater, then reducing groundwater pumping can be effective in slowing down or completely halting coastal land subsidence,” he said.

Ohenhen added that a number of defense structures were identified in the research that could be put in place, including nature-based protection using marshes and mangroves, subsidence control in cities subject to anthropogenic-caused land sinking, land use planning, and a combination of these will be effective in adapting to the identified consequences.

Marine Geologist Dr. Stan Riggs, distinguished research professor and Harriot College Distinguished Professor of geology at East Carolina University, when asked for his thoughts on the study, told Coastal Review that he and the other scientists he’s worked with over the last 60 years have known that there’s been a subsidence component, “but we were never able to sort it out. And I think I’ve just finally solved that problem,” which he added will be detailed in his book being published later this year.

“The Atlantic Coast here is intermediate. In the case of North Carolina, Wilmington is the most stable part of our whole coastal plain,” Riggs said, and “you would expect to get a minimum amount of compaction down there. For example, if you drill a hole in Wilmington, you go down 1,000 feet, you get granite, up here in this part of the state you go down 10,000 feet to hit granite. There’s a lot more sediment up here and so the compaction is going to be higher,” he said about the area of his residence in northeastern North Carolina.

In the Coastal Resources Commission’s 2015 sea level report written by its advisory science panel, the coastal plain was broken down into four quadrants, with Wilmington having the lowest rate of sea level rise and “the highest by quite a bit being the Albemarle embayment, everything from Croatan National Forest north into the northern part of North Carolina,” Riggs said.

At the time, the science panel couldn’t separate out how much of that was subsidence versus regular sea level rise, “so we focused on regular sea level rise, because we didn’t know how to measure the vertical subsidence,” Riggs said. “I’ve now got data and some capabilities of measuring elevation changes down to a half an inch over time.”

In the northeastern part of the state, where there are thick areas of peat, there’s been as much as two to three feet of subsidence in the last 200 years which is pretty significant,” and regarding increasing ghost forests, “that’s partly because everything’s sinking in addition to the sea level rise, and it’s happening really fast now because we’ve ditched the living hell out of this area. For 250 years now we’ve been ditching and there’s probably more than hundred or several hundred thousand miles of ditches and it’s all starts out as peat land and peat is organic matter and organic matter oxidizes if it dries out.”

What he said is important about the study is that it demonstrates that subsidence is real and highly variable depending on “where you are and what the conditions are, what the history is now and what the geology ecology is. All of that has to go together to try to understand and manage the coastal system.”

Being variable is one of the most important points, Riggs said adding, that in some places, subsidence is equal to the rate of rising sea levels, “which doubles the whammy of sea level rise.”