A team of North Carolina scientists and researchers have less than two years to develop a proposal that will convince the National Science Foundation that eastern North Carolina is ripe to become an engine of innovative ecosystem technology that could advance a new workforce and a resilient and sustainable economy.

If the North Carolina Ecosystem Technology, or NCET, project is chosen, an infusion of $160 million will pour into the region over the next 10 years, potentially igniting a transformative science-based zeitgeist, similar to the launch in 1958 of the acclaimed research institute in the Raleigh area that merged science, academics, government, business and technology.

Supporter Spotlight

“What we want to do is to create something analogous to Research Triangle Park,” said Reide Corbett, executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute and the dean of Integrated Coastal Programs at East Carolina University.

After the National Science Foundation announced an opportunity to compete for funds in a new program, the team submitted a letter of intent. In May, they learned they would be awarded $1 million to write a full proposal.

What’s different about the proposed ecosystem technology, or eco-tech, project is that the work concepts would be generated where people live and work in eastern North Carolina, driving economies from the ground up, Corbett said.

By providing multiple connections with the community, as well as infrastructure and resources, he continued, the goal would be to build “an innovation hub that allows for use-inspired development … to support individuals who are trying to solve problems for the East, in the East.”

The National Science Foundation program as a whole, he added, is focused on reaching folks in less populated, remote communities, many of which are vulnerable to climate change impacts or economic decline.

Supporter Spotlight

“This is really about building opportunity for rural North Carolina, building opportunity for these areas that are outside of these regions that typically have plenty of workforce, plenty of innovation,” Corbett said. “It’s trying to move the capability and the opportunity beyond Raleigh Durham and that area.”

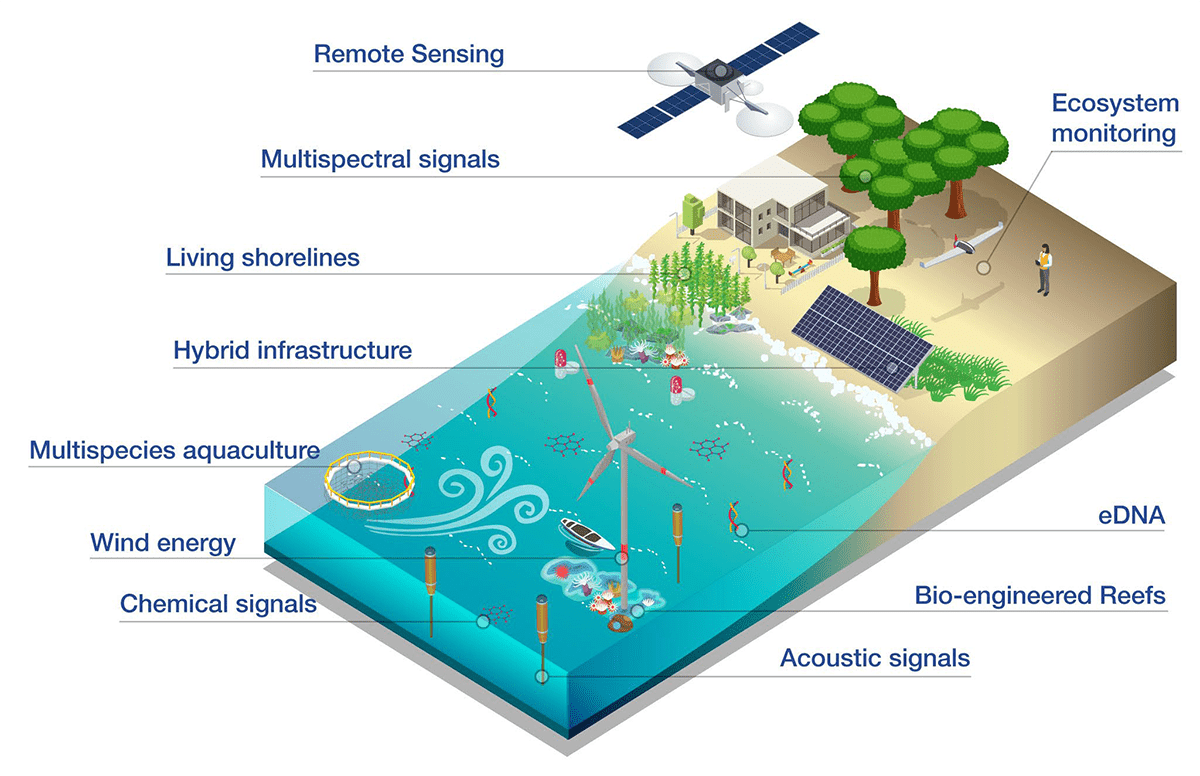

Eco-tech, defined as solutions-based applied science that uses living eco-systems to produce and enhance products, is billed as the next bio-tech, which studies biological attributes of organisms to use in products. If true, that would bode well for the potential growth of eco-tech.

Biological technology evolved over the centuries from modest techniques such as beer-brewing to today’s groundbreaking work on human genomes, proving the value of collective, collaborative and cooperative science research.

Research Triangle Park, as a business incubator and a hub of creative energy and scientific brainpower, is credited with propelling the explosive growth of bio-tech. It also helped revitalize the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area into one of the nation’s most dynamic regions.

Corbett is one of 11 principal investigators working on the NCET project, in addition to Brian Silliman, a marine conservation biology professor at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, and Kenneth Halanych, executive director of the Center of Marine Science at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and who also serves as the director of the NCET consortium and grant administration.

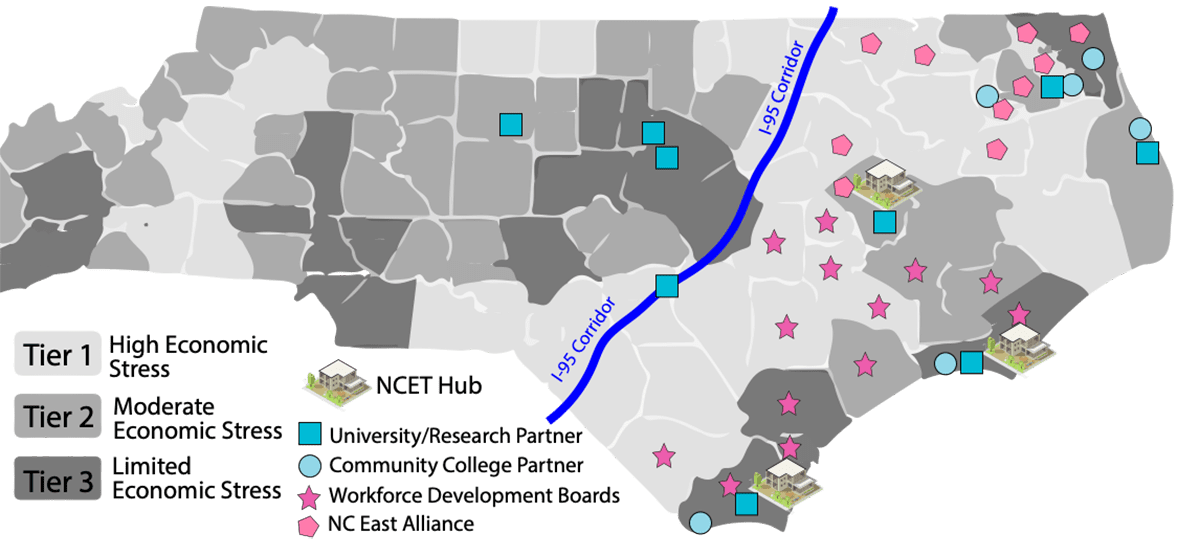

As Halanych puts it, NCET is “a multi-institutional” project, that is equal parts Duke, Cape Fear Community College, Carteret Community College, ECU, North Carolina State University, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, and the Research Triangle Institute.

According to a brochure about the prospective National Science Foundation engine award, the NCET concept would initially focus on renewable energy, aquaculture and infrastructure as vehicles to translate what people (“users”) see as a need into marketable, planet-friendly products.

The work would network across universities and partner with businesses, nonprofits and other community entities to conduct research and bottom-up innovation. As a result, communities would be more resilient, workforces diversified and engaged and regional economies strengthened.

Halanych explained that the eco-tech grant is a byproduct of the National Science Foundation’s new directive expanding basic science and discovery to applied science, economic and workforce development. Called the NSF Engines Program, he said, its goal is to drive workforce development by “use-inspired” innovations.

“What that means is, instead of scientists sitting in the lab trying to think about what they want to do, it’s really about looking to the community and looking to the context of the community —‘What do you need?’ ‘Are there innovations that we can help develop that will push community needs forward, municipal needs forward, individual needs forward?’” he said.

“And so, it’s sort of bringing science out of the ivory tower a little bit with the hope that it will drive economic development.”

If the prospective NCET team’s plan makes the cut for the $160 million award, he said, it would have 10 years “to jump-start innovation” within the whole region east of the Interstate 95 corridor.

With a mix of coastal and rural areas that depend on land — whether for eco-tourism, farming or forestry — the region is ripe with opportunities for eco-tech, Halanych said. The approach is to use technology to work with, not against, the environment to build in a more sustainable way.

For instance, NCET could help with building jobs to mitigate climate change impacts with innovative technology, such as installation of living shorelines made with 3D printed oyster reefs, he said.

Markets could be created for new kinds of adaptive wastewater disposal systems, which would require trained engineers, contractors and installers. Or in the case of flooding, whether from water bodies or rain deluges, building more affordable — therefore, more accessible — water sensors could radically improve a community’s ability to respond and react in real time to flooding events. “That’s workforce development,” Halanych said. “That’s new job opportunities.”

In a competitive process that started off with more than 950 proposals before being pared down to 30, the NCET team has about 18 months remaining before the proposal is due for submission to the science foundation, Silliman said. “Maybe five or six teams among 30 proposals will be selected for the $160 million. We’ve made it to the final round.”

Silliman, who expressed optimism about eastern North Carolina’s prospects for the final award, said that NCET would be divided into three place-based hubs where businesses, academics and community leaders congregate, with the potential to expand further into smaller hubs. The National Science Foundation, he said, is encouraging scientists to be nimble and responsive.

“This is an innovation hub that’s doing science, innovative science on topics that the people of eastern North Carolina want to see covered,” he said. “Then, we foster small business development around these hubs that hires people who were born in these areas, so they can stay there.”

The team is already working with existing networks and tapping into existing community surveys, Silliman said. The project would include community meetings, and public input would be coupled with data to provide a picture of risk and vulnerability, as well as what the community’s is worried about in the next decade.

“And then we would have discussions about how innovative science that fuels business development can help address those issues,” he said, “and whether they are interested in something like that.”

The value of eco-tech is not just inventions of new products to use in the environment, but also in utilizing, enhancing and adapting existing products. Ecosystem technology, like biotechnology, can interact with any sector, he said.

“One of the things we want to help with in eastern North Carolina is the technology is to monitor the performance of really important infrastructure that we have in the coast,” Silliman said. “That would be our hybrid and hardened shorelines as well as as well as our septic systems. So right now, we don’t have a good handle on either one.”

Eco-tech can be taken from the imagination to the research lab to the market with a collaborative like NCET, Corbett said. It can provide the linkage.

“A lot of what’s missing is that connection between somebody that has an idea, or maybe even has developed a product,” he said.

“It’s how they take it to the next level and a lot of times it’s the understanding of how to do that,” Corbett said. “It’s the capacity of being able to create.”