Note from the author, North Carolina historian David Cecelski: This is an updated version of a short essay that I first published two years ago. To write this version, I drew on additional research that I did in preparation for giving a special lecture to mark the New Bern Historical Society’s 100th anniversary. That event was held Nov. 12 at Craven County Community College in New Bern. The event was sold out and I was deeply impressed at the local interest in the subject.

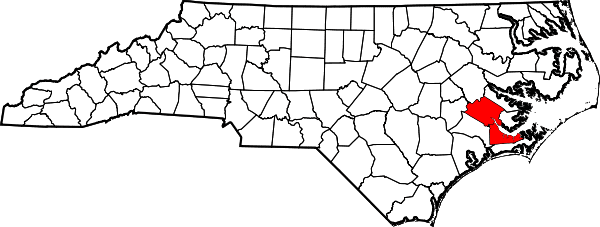

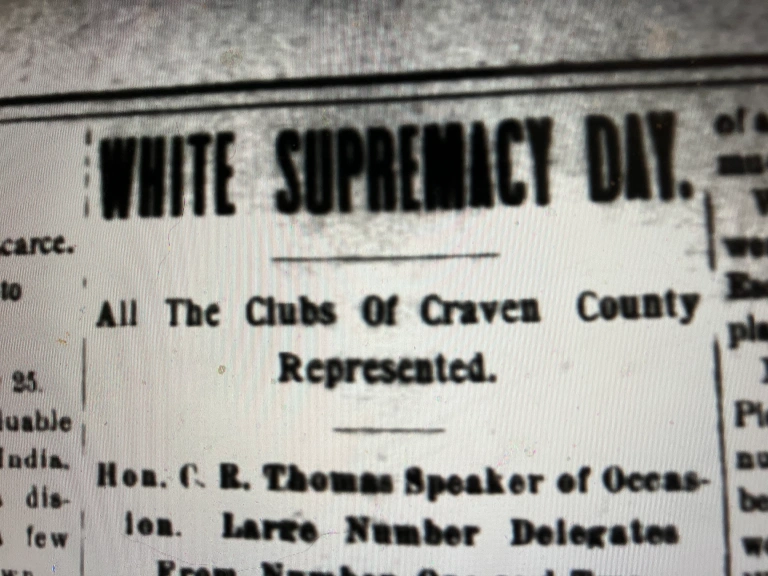

A friend in New Bern recently sent me an issue of the Raleigh News & Observer that he found in his family’s old papers. The newspaper’s date was Nov. 5, 1898. A front-page article was about a large white supremacy meeting at the Craven County Courthouse in New Bern.

Supporter Spotlight

That was only a few days before the massacre of Black citizens in Wilmington that was in the news so much a few months ago.

Wilmington, the state’s largest city at that time, was 90 miles from New Bern. However, as I read the issue of the News & Observer that my friend sent me, I couldn’t help but feel that what happened in Wilmington could easily have happened in New Bern, too.

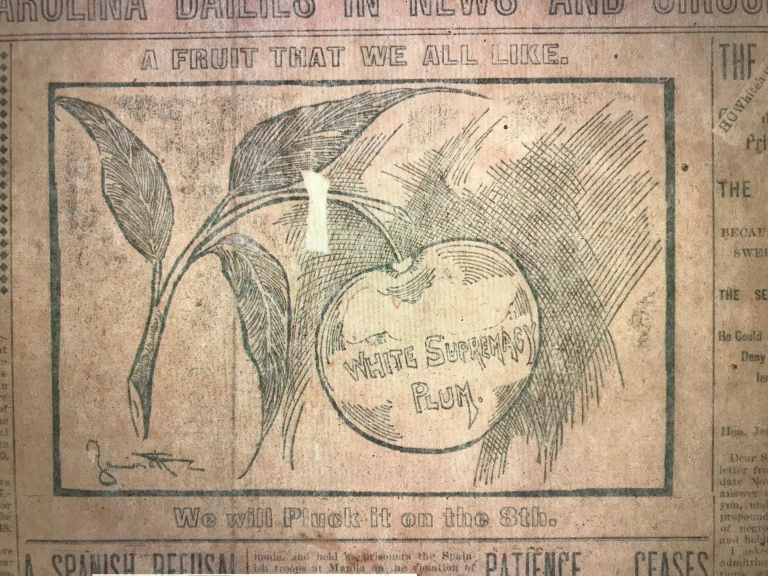

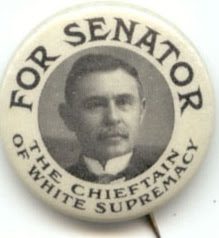

‘White Supremacy Plum’

On that fifth day of November 1898, the News & Observer featured a large drawing of a plum on the top of its front page. The artist had labeled the fruit “White Supremacy Plum.”

Above the drawing was a headline: “A Fruit We All Like.” Below the drawing was another headline: “We Will Pluck It on the 8th.”

The Nov. 8, 1898, was the date of the fall elections. At the time, the News & Observer was playing a central role in a white supremacy movement that reached across North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

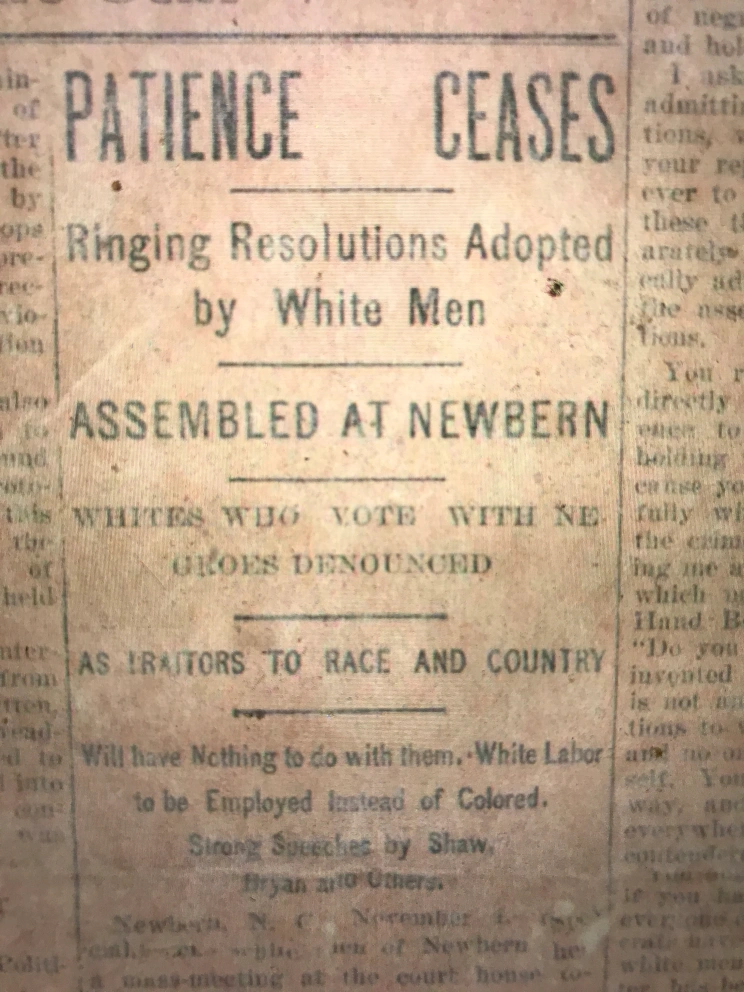

The story from New Bern appeared under the drawing of the “White Supremacy Plum.” Its headline read:

PATIENCE CEASES: Ringing Resolutions Adopted by White Men

With a summary of the story’s content appeared beneath those words.

WHITES WHO VOTE WITH THE NEGROES DENOUNCED

as traitors to race and country

Will have Nothing to do with them, White Labor To Be Employed Instead Of Colored, Strong Speeches by Shaw, Bryan and Others

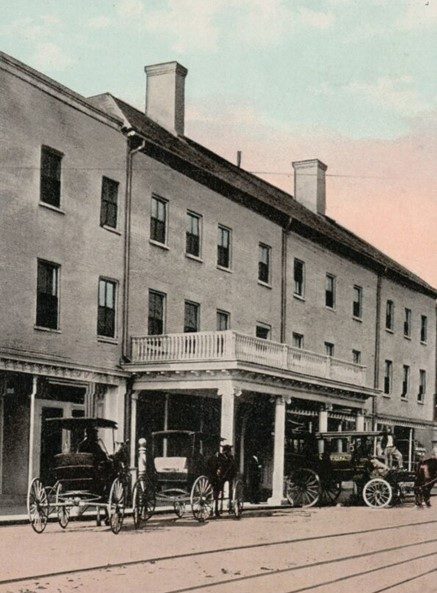

The story began below those words. According to the newspaper’s correspondent, a mass meeting of “the white men of Newbern [sic]” had been held at the Craven County Courthouse. At that meeting, many of the town’s wealthiest and most influential white citizens had gathered to make a statement on white supremacy.

The chairman of the meeting was Alfred Decator “A.D.” Ward, a prominent local attorney. He was originally from Duplin County, where he had been mayor of Kenansville and where he had been elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives.

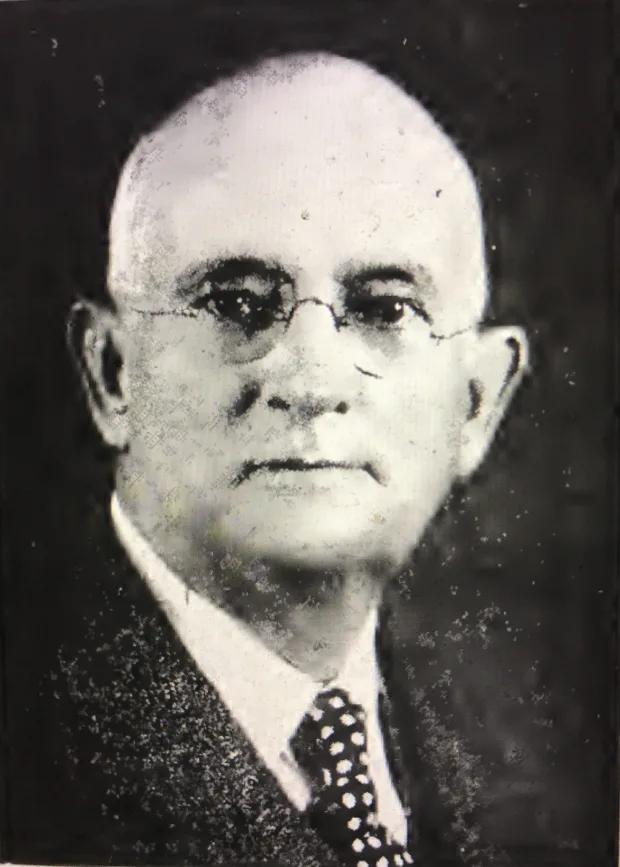

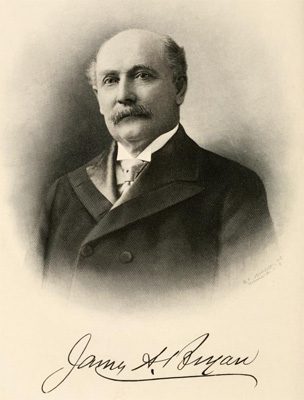

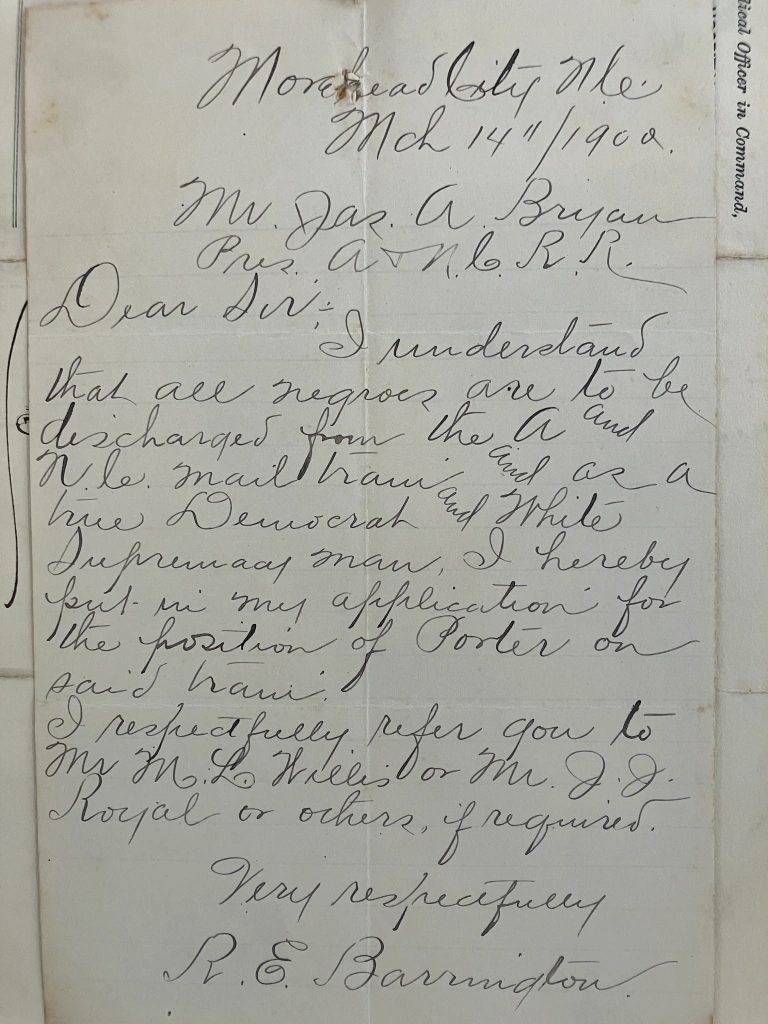

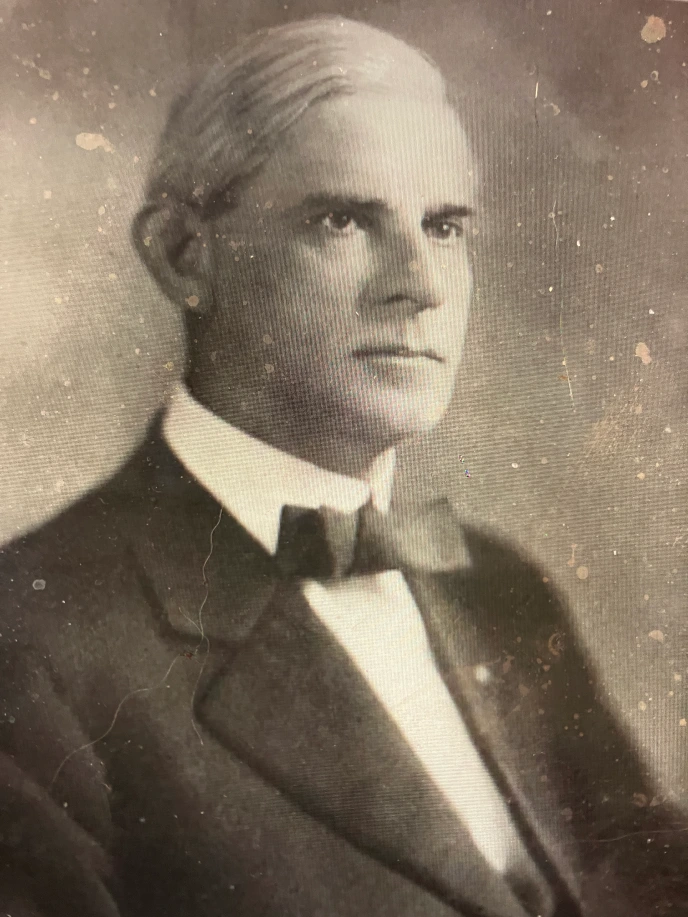

Probably the most prominent of the city leaders at the meeting was James A. Bryan. At the time, Bryan was the president of both the National Bank of New Bern and the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad Co.

He was also one of the largest landowners in the state of North Carolina. His holdings included, but were not limited to, more than 57,000 acres in what is now the Croatan National Forest.

Bryan owned and resided in what is now known as the John Wright Stanly House, which is one of the historic sites at Tryon Palace. Educated at Princeton, he later chaired the Craven County Board of Commissioners for two decades and served a term each as mayor of New Bern and state senator.

According to the story in the News & Observer, both James A. Bryan and A.D. Ward were among the local leaders that gave “enthusiastic and patriotic speeches” during the white supremacy meeting.

‘Deliverance from Negro Domination’

At the Craven County Courthouse, the white leaders passed five resolutions that were very similar to ones that the white supremacists in Wilmington passed that same week, just prior to the massacre and coup d’etat there.

In the first resolution, they resolved that:

“It is the duty of every white person, male and female, to do everything in their power to achieve an honorable deliverance from negro domination and its accompanying ruin and disgrace.”

At that time, African Americans made up about 65% of New Bern’s population. In any free and fair election, Black citizens would inevitably have held a significant number of offices.

The town’s African Americans did hold some elective offices, but relatively few. Black citizens held three of the 11 positions on New Bern’s board of aldermen, for instance. That was a large number compared to many other North Carolina towns, but far from what one could reasonably call “negro domination.”

In this first resolution, the white supremacists were announcing that they would no longer tolerate even that degree of Black participation in politics in New Bern or the rest of Craven County.

‘Traitors to their race and country’

The meeting’s second resolution read:

“That it is the sense of this meeting that from henceforth all white men who vote and ally themselves in politics with the negro shall be denounced and regarded as traitors to their race and country and as public enemies, and not to be associated with.”

A duly elected political coalition of Republicans (largely Black) and Populists (largely white) had governed North Carolina since 1894. In this resolution, the city’s white supremacists were threatening their white neighbors who persisted in supporting that coalition of Black and white voters.

The language of the resolution is noteworthy. In many parts of the world, and at many different times, extremist political movements have begun to refer to their political opponents as “public enemies” and “traitors to their race and country.” It is never a good sign, and of course it is often a prelude to great violence and widespread persecution.

The white supremacists in Wilmington also used that kind of language just before the shooting started.

‘Traitors to the white race’

The meeting’s third resolution read:

“That we denounce such traitors to the white race as make a business of organizing the negro, and we hereby warn [them] to desist from their efforts to further ruin and humiliate the white people ere the day of forbearance shall pass and the time shall come when an outraged people shall realize that such creatures are nothing more than beasts of prey to be driven away.”

In this resolution, New Bern’s white supremacists continued to use language that demonized their opponents. In this case, they were threatening local white leaders of the Republican Party.

Calling them “beasts of prey” also sounds very much like Wilmington just before the shooting started.

‘Brave and honorable men’

The meeting’s fourth resolution read:

“That while our brothers of the white race in other communities are bravely daring all danger to rid themselves and us of the dark cloud of negro domination, it behooves us to encourage them with the assurance that we, too, have resolved to use every means that brave and honorable men may for the deliverance and salvation of our State from the horrible fate which threatens.”

In this resolution, the white supremacists in New Bern were making clear that they knew what was about to happen in Wilmington and they supported it.

That they knew what was going to happen in Wilmington was not surprising. By the Nov. 5, 1898, it was widely known that white supremacists were planning to take control of Wilmington three days later, even if they had to resort to violence in the streets, massive electoral fraud and military rule.

Newspaper reporters from as far away as Chicago were already on their way to Wilmington because they had gotten wind of the coming storm.

In this resolution, New Bern’s white supremacy leaders signaled that they knew what was coming in Wilmington, too. They also seem to be saying that they would take similar steps in New Bern if necessary.

‘Preference to white people’

The white supremacists in New Bern intended the fifth and final resolution to encourage New Bern’s poor and working class white men to support their efforts. The resolution read:

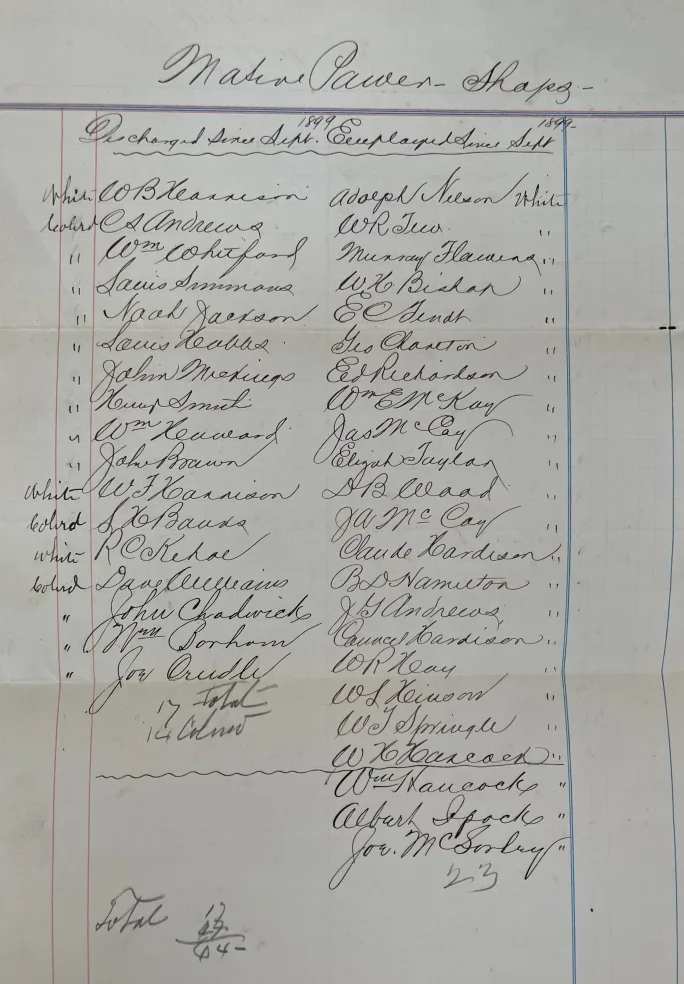

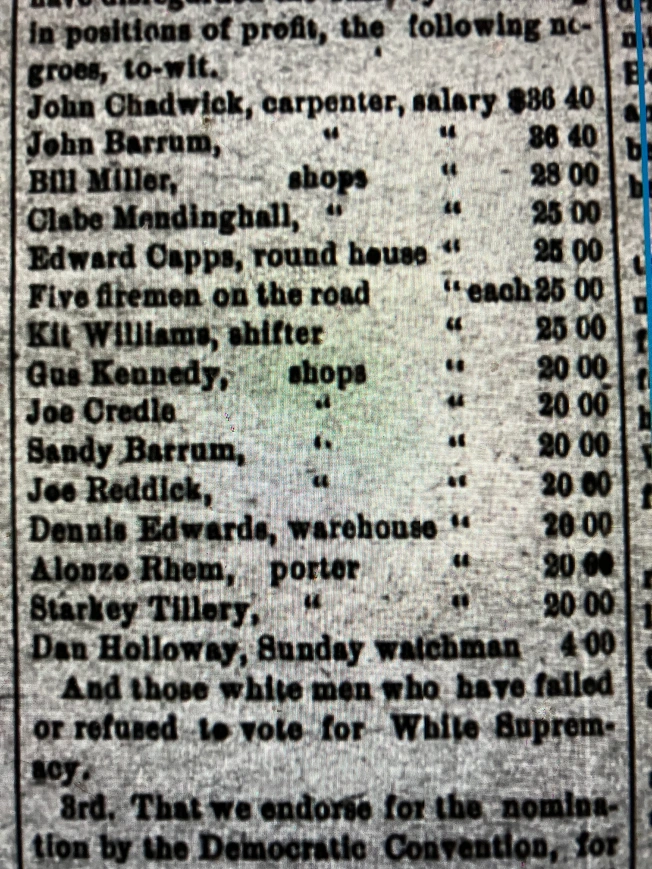

“That we, the employers of labor, will give preference to white people in all cases wherever practicable.”

In this resolution, the town’s leading businessmen were promising white workers that they would hire them in their shops and factories over Black workers, even if the Black workers were more qualified and had more experience, if the white workers supported the “white supremacy ticket.”

They were, in effect, cutting a deal: side with us, and not your fellow Black workers, and we will look out for you.

The same thing happened in Wilmington.

The business leaders in both cities proved true to their word. In the coming years, that kind of racial discrimination in employment became universal, and as much a part of Jim Crow as separate drinking fountains and segregated lunch counters.

A different kind of coup d’état

The Nov. 8 election was said to have passed peacefully in New Bern, though we know very little about what might have happened there and gone unsaid.

We do know though that the white supremacists prevailed. There was a bright spot or two for the town’s Black citizens: Isaac H. Smith, a prominent local Black businessman, for instance, won a seat to the NC House.

But he was the exception. The white men at the meeting that the News & Observer described on Nov. 5, 1898, became the town’s mayors, aldermen, county commissioners, educational leaders, state legislators and U. S. congressmen for the next generation.

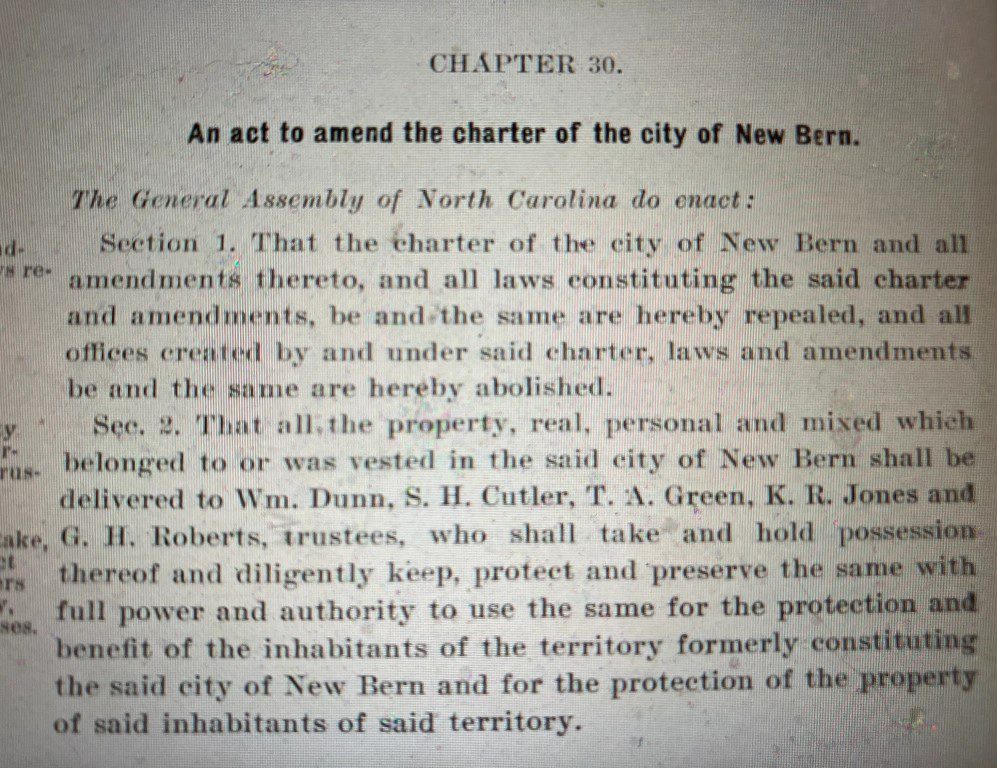

We also know that, in the weeks after the election, the white supremacists did not wait for the town officials that had not been up for re-election in 1898 to serve out their terms before they moved to replace them. They instead convinced the state legislature to dissolve the city’s charter and throw all of their political opponents, both Black and white, out of office.

The North Carolina General Assembly voted to repeal New Bern’s charter on Feb. 3, 1899. At that time, the legislators put the city’s assets under the authority of a small group of trustees.

The act went into effect a week later, Feb. 10, 1899.

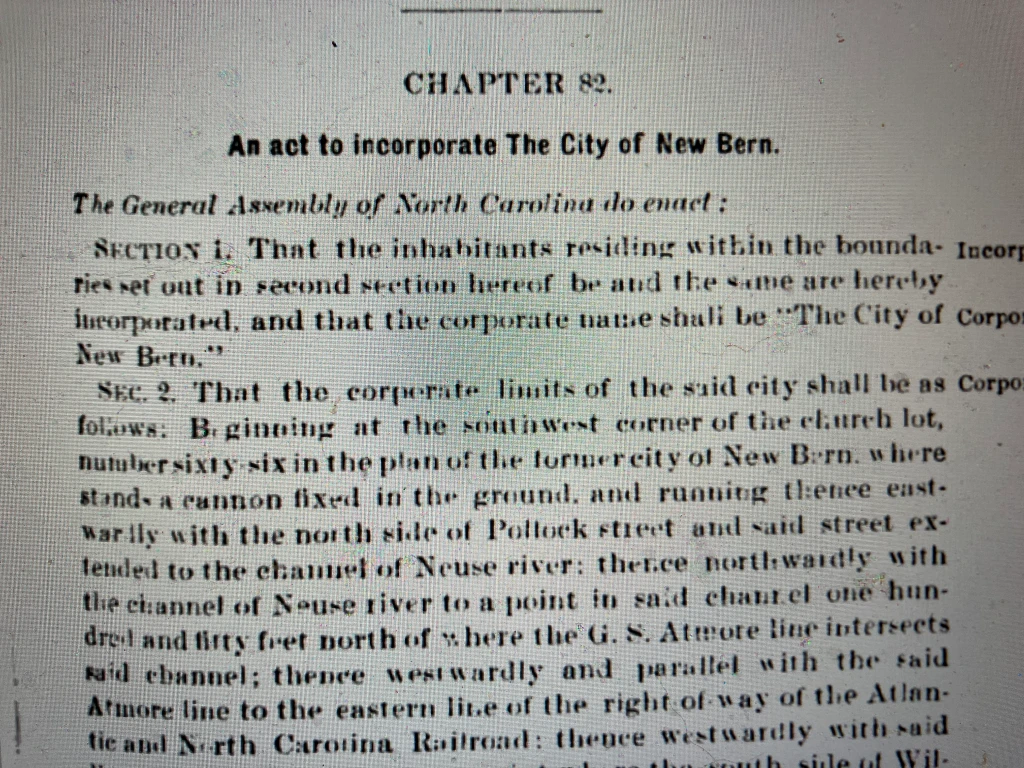

Ten days later, the General Assembly passed another act to incorporate the City of New Bern. The legislators named a new board of aldermen, purged the city’s voter rolls, and set a date for elections later that spring. When the new charter went into effect Feb. 20, 1899, white supremacists held all the power in the city.

For the sake of white supremacy, the City of New Bern did not exist for those 10 days.

For more on that chapter in the city’s history, see Dr. Thomas Hanchett and Ms. Ruth Little’s excellent 1994 report on the history of two of New Bern’s African American neighborhoods, Long Wharf and Duffyfield.

In that way, the white supremacists in New Bern accomplished their own kind a coup d’état, much like what happened in Wilmington. Their coup was bloodless, as far as we know, but just as effective.

It could have been even worse. Judging from the Nov. 5, 1898, issue of the News & Observer that my friend shared with me, I find it hard not to think that, if things had gone just a little differently, and if a spark had been lit, we might well be talking about bodies in the streets of New Bern, too.

~

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who shares on his website essays and lectures about the state’s coast. He brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives where he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.