With the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Florence this month, many on the coast are reliving the stress caused by catastrophic flooding, extensive damage to property and infrastructure, and the continued long-term recovery.

The Nation Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calculated that the 2018 hurricane was one of the costliest tropical cyclones to impact the U.S. coming in at $29 billion, based on the 2023 Consumer Price Index-adjusted cost. But that’s just the financial toll.

Supporter Spotlight

“Weather-related disasters are increasing in frequency and severity, leaving survivors to cope with ensuing mental, financial, and physical hardships,” which can exacerbate existing illnesses or cause new, and increase the risk of mortality – also characteristics of advanced age – leading to the hypothesis that extreme weather events may accelerate aging, according to “Natural disaster and immunological aging in a nonhuman primate,” a research paper published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To test this hypothesis, researchers looked at blood samples of individual, free-ranging rhesus macaque monkeys on an isolated island in Puerto Rico. The authors compared samples from monkeys that were exposed to the 2017 Hurricane Maria to samples of those that were not. They found that the monkeys exposed to the hurricane had a gene expression profile that was, on average, two years older.

This is “roughly equivalent” to seven to eight years of human life, primate comparative geneticist Julie Horvath, told Coastal Review. “If a human gets exposed to severe hurricanes like this, maybe they’re going to age seven, eight years faster.”

Horvath, along with colleagues from Arizona State University, Caribbean Primate Research Center, University of Pennsylvania, University of Exeter, New York University, collaborated in the study.

Horvath is the head of the Genomics and Microbiology Research Lab at North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and has a co-appointment as a research associate professor in the biological and biomedical sciences department at North Carolina Central University.

Supporter Spotlight

She is also part of a public science project that seeks to involved middle school and high school teachers and students in researching monkey health, including a workshop for middle school and high school educators later this month.

In 1938, about 400 monkeys were relocated from India to the Caribbean Primate Research Center field station on the isolated island, Cayo Santiago, a nearly 40-acre island off the southern coast of Puerto Rico.

Researchers first studied the behavior of these highly social primates that are a close relative to humans, then their pedigree.

In the last 15 to 20 years, Horvath said they’ve been studying genetics and health of the about 1,500 monkeys on the island, all descendants of that first generation. The scientists collect blood samples and compare the blood count information with the behavioral measures to see how animal health contributes to differences in their behavior.

After Hurricane Maria hit the region in 2017, Horvath said they realized that they could compare samples, initially collected to study overall health, from before and after the storm to determine if a natural disaster can molecularly accelerate aging in the monkeys’ immune system.

Rhesus macaque monkeys share many behavioral and biological features with humans, including aging characteristics, though their lifespan is a quarter of a human’s. “They’re really great models overall, but they also are useful because they age faster than humans so you can study aging in them,” she explained.

“To test this idea, we examined the impact of Hurricane Maria and its aftermath on immune cell gene expression in large, age-matched, cross-sectional samples from free-ranging rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) living on an isolated island,” the study states.

“We know that when humans experience traumatic life events it can have lasting impacts on their health and mental state. Our research underscores the importance of ongoing studies in these rhesus macaque monkeys to help us better understand the factors impacting health and aging across all primates, including humans,” Horvath said in a statement when the study was published.

Aging studies look at gene expression, or how your genes differently turn on or off, as you get older, and researchers were able to observe gene expression differences between monkeys that were exposed to a hurricane versus not exposed.

“So essentially, you’re aging a little bit faster if you get exposed to one of these extreme natural disasters like a hurricane,” Horvath told Coastal Review. Adding that macaques are a good model to study the aging process, and that can translate to what happens in humans who are exposed to natural disasters.

For example, people with higher socioeconomic status, good health care and access to food who are exposed to hurricanes probably can continue to maintain that through hurricanes, but people with a lower socioeconomic status that can’t obtain food or maybe don’t have access to fresh water would add those other confounding factors.

The macaque monkeys on the island are provided food, so they all have a very similar diet, and don’t have intervening veterinary care, which removes the variables of food insecurity and differing medical care.

In that sense, she said, the macaques are a model that just says the hurricanes trigger emotional and physical stress on them.

“That’s probably a better predictor of how the aging process goes. And then in humans, you’d probably see a lot more variation across humans because there’d be these confounding factors of socioeconomic status, food, access to medical care, etcetera. I think then, in that sense, the macaques are a really great model for some of these studies.”

Horvath is on the team for an online public science project, the Monkey Health Explorer, launched five years ago through Citizen Science Alliance’s web portal, Zooniverse. Part of the international collaboration to better understand how genes influence social behavior using macaque monkeys as a model, scientists can use the data to better understand the same kind of processes in humans.

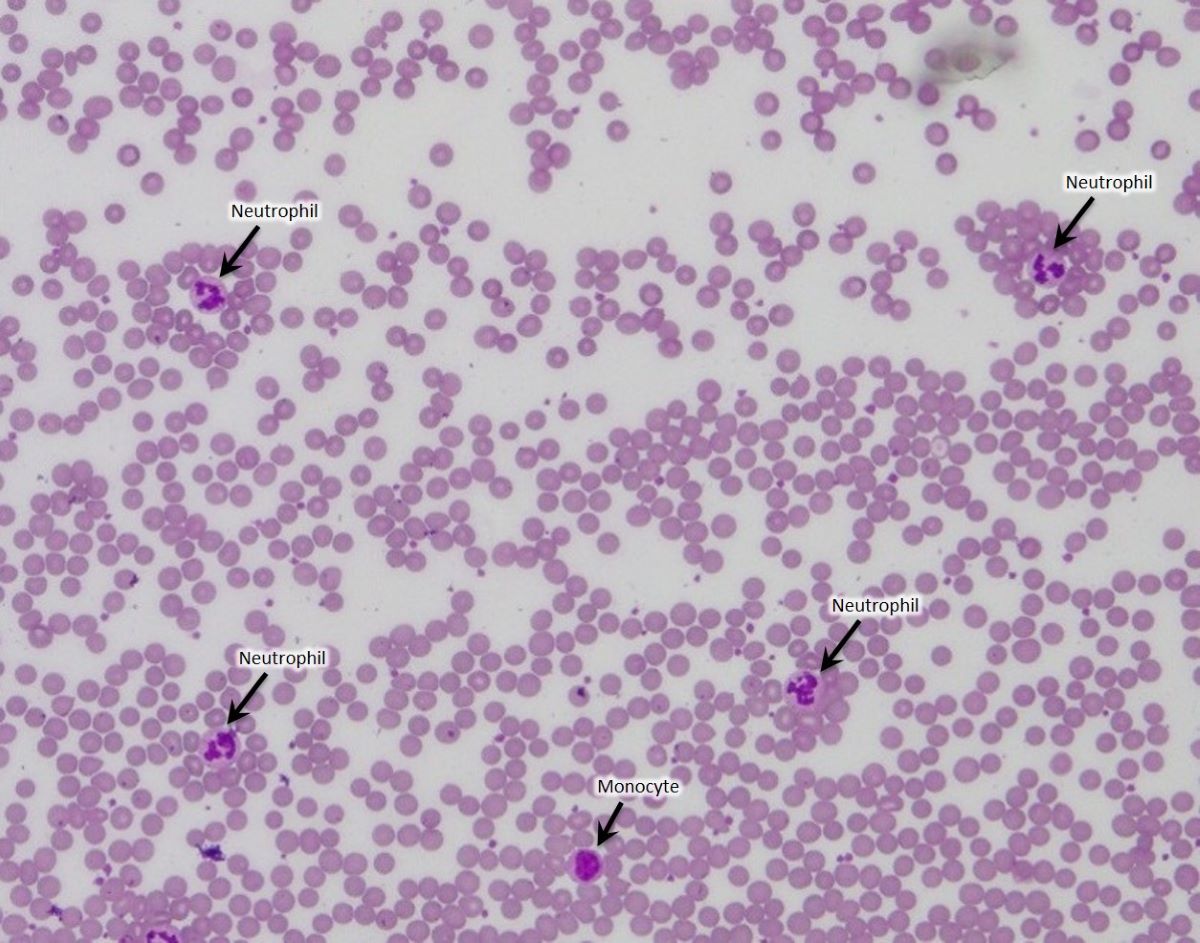

There is a tutorial and field guide for new volunteers on the site to learn how to count and identify cell types in the images of blood smears collected from hundreds of these monkeys uploaded to the online platform.

Horvath said that her lab is focusing on the public science project because everybody can contribute.

They’re trying to get more sixth through 12th graders to participate so the students can learn what monkey research can teach us about humans.

The museum is offering a new workshop on the project for middle school and high school biology, Earth, environmental science and math teachers on Sept. 30 at the facility in downtown Raleigh.

Register online for Educator Trek: Monkey Health Explorer. Fee is $25 due at time of registration and teachers can earn hours for North Carolina’s Environmental Education Certification Program.

The goal is to engage teachers and students in authentic research and to provide a platform for clinically interested students to gain valuable career experience, according to the release.

Horvath said the workshop to be held at the museum in Raleigh will include hands-on activities, print outs of the lesson plans, and supplies for teachers to take home so they can have the activity in their classroom without needing to purchase items or print documents.

For those unable to make it to Raleigh but have an interest in the lesson plans and materials, the documents are available online. Horvath said if there’s enough interest, the museum will consider hosting an off-site workshop.