I discovered another forgotten chapter in eastern North Carolina’s history while I was exploring the Farm Security Administration, or FSA, photographs at the Library of Congress. It is a story about the migrant farm workers that harvested the region’s crops in the 1930s and ’40s.

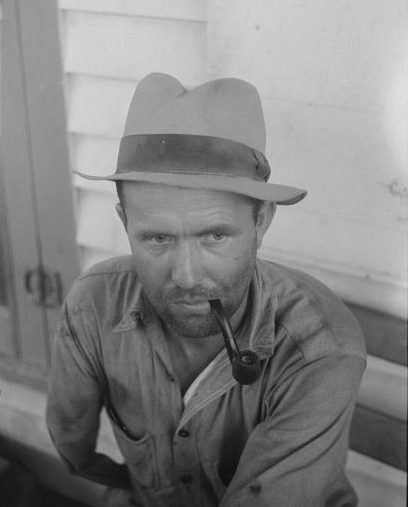

An FSA photographer named Jack Delano took the photographs that caught my eye. He’s the same photographer that took the photographs of the migrant construction workers at Fort Bragg that I discussed here.

Supporter Spotlight

A talented photographer and composer, Delano was a Ukrainian Jewish immigrant who had come to the U.S. with his family in 1923, when he was 9 years old. All of his photographs show a warmth and sympathy for others and a special concern for the down and out.

He was one of an extraordinary group of photographers that worked for the FSA during the Great Depression and the Second World War. They included figures such as Dorothy Lange, Gordon Parks and Marion Post Walcott that are now icons in the history of documentary photography.

Delano took the photographs of migrant construction workers at Fort Bragg in March of 1941. But nine months earlier, when the FSA was still focused on the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, he had spent time with other migrant workers in a different part of eastern North Carolina.

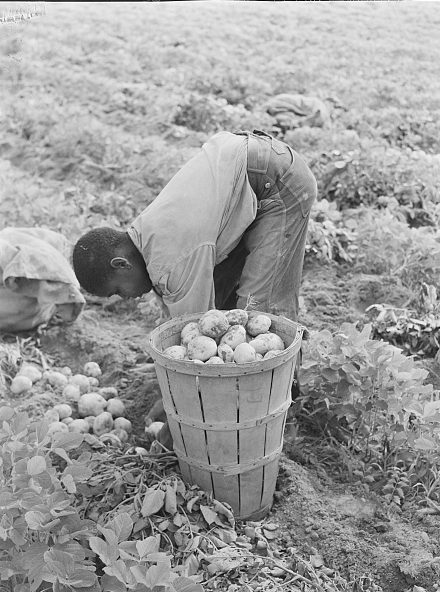

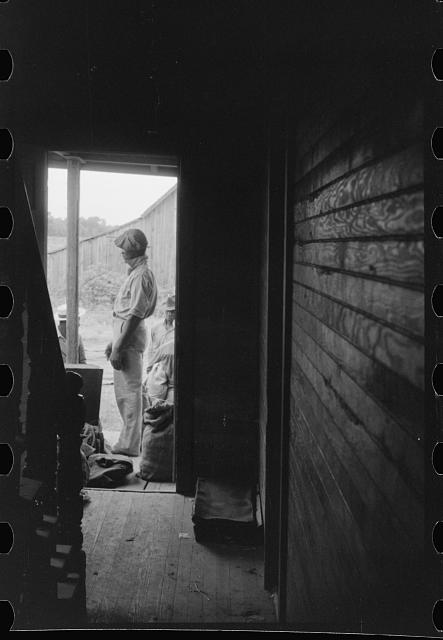

In the summer of 1940, he took a remarkable series of photographs of the migrant laborers that harvested and packed potatoes in a group of counties not far from the Outer Banks.

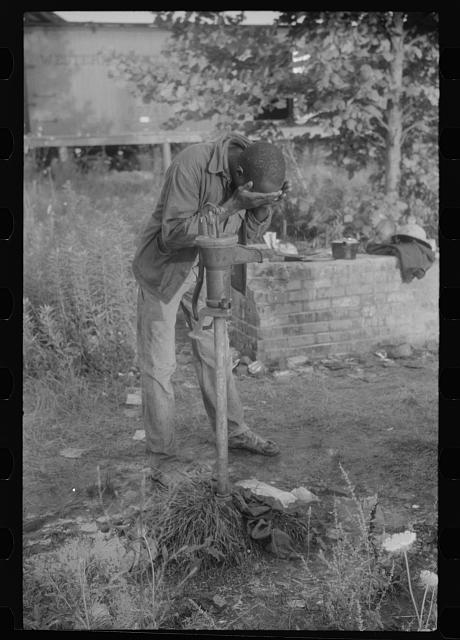

Traveling up and down the East Coast, those men, women and children worked in orchards and fields from Florida to New Jersey.

Supporter Spotlight

In the wintertime, most worked in the citrus groves and vegetable fields of South Florida. They lived in sprawling camps of laborers in places such as Belle Meade, Immokalee and Homestead.

When they finished the harvest in Florida, they worked their way up the East Coast. The farm laborers in Delano’s photographs harvested potatoes here in North Carolina in June and July, then headed to jobs further north. Delano reported that they traveled next to Onley, a village on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, and to Cranbury, a small town in southern New Jersey.

That summer of 1940, Delano photographed migrant farm workers in Shawboro in Currituck County, N.C., and in Camden, Belcross, Shiloh, and Old Trap a few miles away in Camden County, N.C.

He also photographed migrant laborers grading and packing potatoes in Elizabeth City, in Pasquotank County, N.C. That town of roughly 11,000 people had the closest freight depot to those other communities.

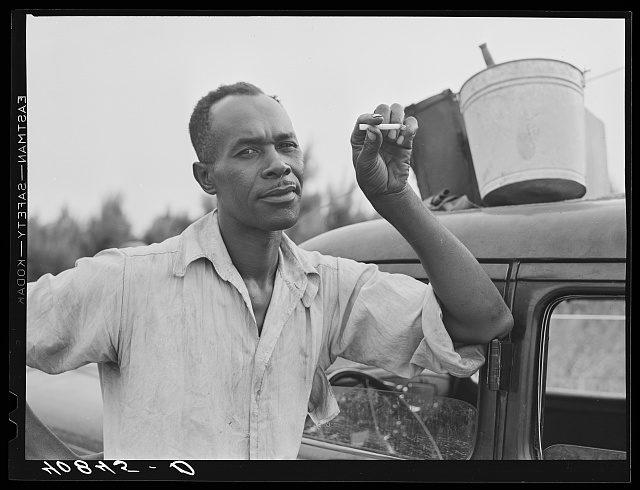

By 1940 migrant laborers had harvested crops in that area and in many other parts of eastern North Carolina for decades. Some had originally come from other parts of eastern North Carolina. Some came from other southern states.

Many had also come to the U.S. from at least half a dozen countries in the the Caribbean, as well as from Mexico.

Hiring migrant workers was one of the ways that farmers replaced the enslaved laborers that had harvested local crops before the Civil War.

During the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of seasonal migrant laborers harvested crops in the U.S.

Those migrants moved across the country, one place to the next, swept up by the Great Depression as if in a great whirlwind and making do until they could get a toehold somewhere.

Today approximately 150,000 migrant farm laborers and their dependents come to North Carolina every growing season. Most were born in Mexico, though quite a few are also from Central America.

Sometimes I do not know what to make of documentary photographs. When I look at them, I feel as if I am in a dark room in a strange house and somebody has flicked a light on for just a second, then turned it back off.

It is such a brief, ephemeral look, at least in this case, of people I do not know and a place I barely know and a time that is gone.

I don’t really know who or what I am seeing, except in what I can make out in that split second of light.

Like all of us in those kinds of situations, I do the best I can: I search the lines in the faces of the people in the photographs. I look at their eyes and the way they are dressed.

I look at the color of their skin, their ages, the way they hold themselves. I look for scars on their faces and hands.

I look at the way that they look at the photographer and the way the photographer looks at them.

Of course in this case we can see that the lives of these men and women and children were hard. But without knowing more about their pasts, I do not think that I can tell if their lives as migrant laborers were harder than the lives that they left behind.

By which I mean to say something about the lives they left behind. For most of them, their earlier lives almost certainly involved sharecropping and/or field work on farms wherever they were born and in conditions that still seemed a great deal like slavery.

I suppose that, in a certain light, a life on the road could even be seen as an act of resistance, a refusal to inherit the oppressions of the past and a show of determination to escape a bondage that bound them to somebody else’s land. It could be seen as a gesture, no matter how hard a life they lived in the migrant camps, of courage and freedom.

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

This is a revised version of a photo essay he published a couple years ago, based on new findings at the Library of Congress.