ROANOKE ISLAND — For five years during and after the Civil War there was a vibrant community of formerly enslaved people living on the north end of Roanoke Island, with houses, churches, a sawmill, a hospital, schools and stores.

Virtually no evidence of the little community remains — or has yet to be discovered — other than oral history and some written records.

Supporter Spotlight

With the new Freedom Interpretive Trail being installed along a 1.25-mile wooded path at Fort Raleigh Historic Site, near the site of the island’s former Freedmen’s Colony, a vital, officials say, but under-recognized part of Outer Banks and Black American history will now be vivified by life-sized silhouettes and interpretive signs with biographical details of some residents of the colony, describing hardships they risked reaching Roanoke and explore why the island was considered a haven. The installation is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

“There will be a narrative that includes different quotes that we have from these different folks, so that will be tied into the silhouette that we’re looking at as we walk the trail,” Fort Raleigh lead park ranger Josh Nelson told Coastal Review recently. “And then we have some information in the narrative from that person, quotes that have been put together to give us a sense of who they were and what they were doing here.”

Established in April 1941, the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site was expanded in 1990 from its original 178 acres. Of the total 513 acres that currently make up the park, 355 are actively managed. As Nelson explained, the trail reflects Fort Raleigh’s expanded focus beyond 16th century English settlements that Congress authorized in 1990, including the significant Black American, Native American and Civil War history of Roanoke Island.

“So it’s not an immediate thing that’s happened, but it’s been something that the park has been working toward since that change and that I see this trail project is really just a continuation of our attempt at trying to better share that history of the Civil War,” he said. “And in this case, specifically the Freedmen’s Colony and the Underground Railroad history that the site has.”

The seven exhibits along the Freedom Trail will interpret various aspects of the Black experience on Roanoke Island, Nelson explained in an email.

Supporter Spotlight

“The African American Freedmen’s Colony is still, thirty years later, an under-represented story at the park and this project will offer visitors a greater understanding of the significance Roanoke Island played in the Underground Railroad network,” he wrote. “Building from the site significance — identified in foundation documents — diverse audiences visiting today will identify with the greater history at Fort Raleigh through the experience of the interpretive trail. The current national dialogue around social justice is rooted in stories incorporated within Fort Raleigh and the project will connect that conversation to the park purpose.”

It wasn’t until a granite monument, the First Light of Freedom, was dedicated at the park on Sept. 14, 2001, that Fort Raleigh included significant recognition of the Freedmen’s Colony.

After the Union Army won the Battle of Roanoke Island in February 1862, formerly enslaved people poured onto the island seeking freedom. Within a year, there were nearly 1,000 refugees, according to Patricia Click’s book, “Time Full of Trial.” By 1865, she wrote, the colony had grown to about 3,500 people.

Although the U.S. government had initially supported Roanoke Island’s Freedmen’s Colony as a model permanent colony of freed Black people, Click wrote, it ultimately was abandoned by the Union and ended March 1867.

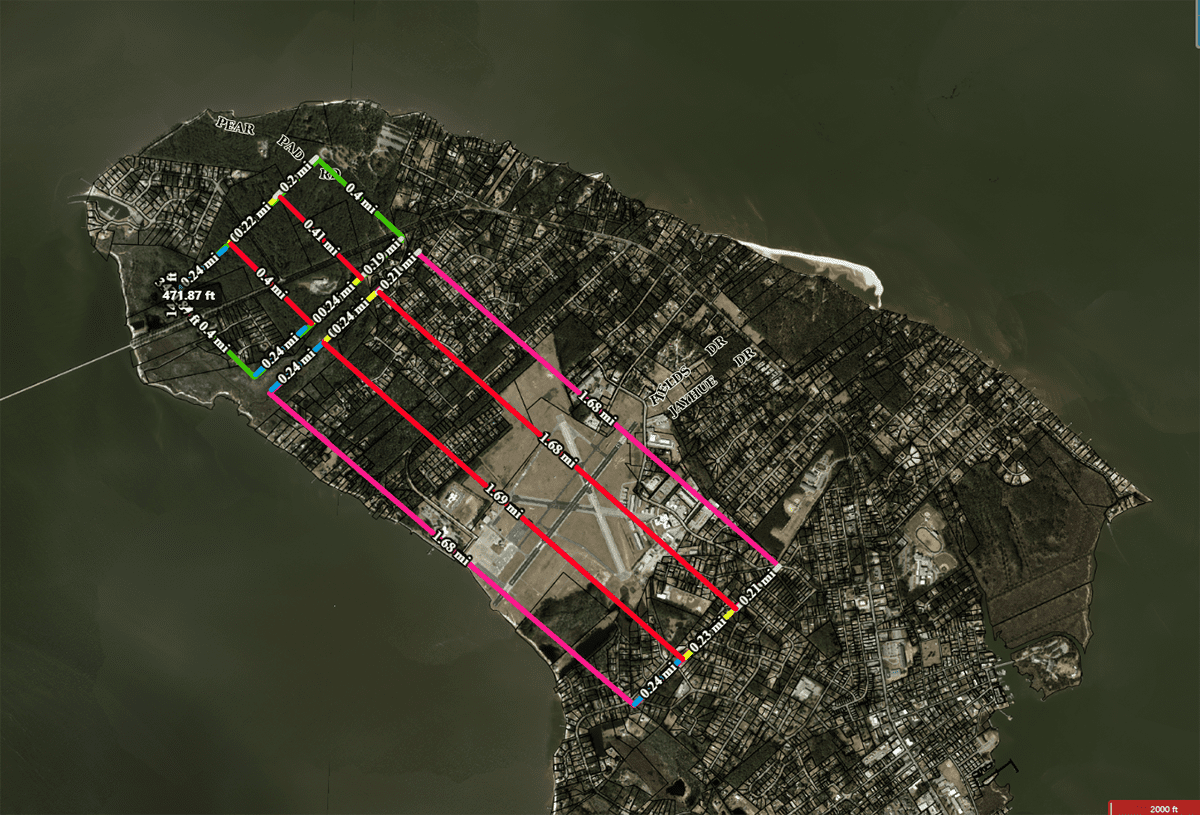

“We haven’t identified precisely where the Freedmen’s Colony was, but we do know the area,” Nelson said. “We know that is was in the area where the airport is today on Roanoke Island, and it extended north underneath where the North Carolina Aquarium sits. The heart of it, where a lot of activity was taking place, was just north of that on Sunnyside Road.”

From there, Nelson said, the colony continued north, with three major streets running northwest to southeast following the direction of the island. Recently, the park was “excited” to learn, he said, that the northern boundary of the colony was at Fort Raleigh where the Freedom Trail runs today.

Numerous residents of contemporary Manteo, including the late Virginia Tillett, a longtime public servant in the community, are descendants of the Freedmen’s Colony.

Constructed of half-inch-thick steel, the life-sized silhouettes on the Freedom Trail will be weathered rather than painted, Nelson said. Accounts of the people from the colony were gathered from published accounts, and from newly unearthed documents found during research at the National Archives and the Outer Banks History Center by park volunteer Cathy Steever and Fort Raleigh park ranger Mike Zatarga.

“We’ve been working on this project since August of last year, and that’s including applying for grants … the research, the transcribing,” Nelson said. All told, 350 pages of handwritten documents were transcribed, in-house and by volunteers. Grants were awarded by the Underground Network to Freedom, (about $7,500); the National Park Foundation, (about $42,000); and Outer Banks Forever, ($2,500.)

As described by Nelson in the email, one exhibit will incorporate history of pre-Civil War enslavement in eastern North Carolina, and attempts to seek freedom, interpreted through three silhouettes of Annice Jackson and her two daughters.

The second one, with the silhouette of Thomas Robinson, will discuss the Union army on Roanoke Island and how local enslaved African Americans assisted in the 1862 Union victory on the island.

A third exhibit will highlight education at the Freedmen’s Colony with a silhouette of student Londen Ferebee.

For the fourth exhibit, the role of missionaries in the colony will be highlighted with a silhouette of missionary teacher Sarah Freeman.

The fifth exhibit, with a silhouette of soldier Spencer Gallop, will represent the 220 men from the Freedmen’s Colony who joined the Union army and navy.

The sixth exhibit, with a silhouette of Fanny Whitney, will demonstrate the hard work done alone by the women of colony.

And the seventh exhibit covers the end of the Freedmen’s Colony and the current community’s connection, depicting Orphan Jim facing the sound and the direction that so many traveled to unknown futures.

Nelson said that the silhouettes are based on what people of that age and era were known to wear and look like, but there are no photographs or paintings of the people in the exhibit. The power is in the actual words, of actual people.

“I belonged to a man by the name of Hodges Gallop at Currituck before the war and worked on a farm,” Spencer Gallop, 19, is quoted in his exhibit. “I escaped to Roanoke Island and cut wood and helped build forts for the Yankees. In 1864, my regiment was assigned as guards at a POW camp containing close to 14,000 Confederate soldiers in Point Lookout, Maryland. Then, in the fall, we fought with distinction in the Battle of New Market Heights, Va.”