First in a series on the Albemarle region’s environmental-economic connections.

Standing on a bluff overlooking the Chowan River at Bertie County’s Tall Glass of Water outdoor education site, North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein spoke last month about the North Carolina Environmental Enhancement Grants, or EEGs, what they have meant to communities, and what they have meant to him personally.

Supporter Spotlight

Stein, speaking during the May 4 event, said awarding EEGs is one of the most fun things he gets to do as attorney general. Addressing organizations selected for the EEGs, he said being able to support the good work of community organizations and civically minded folks was tremendous.

“To see these funds pour back into North Carolina … using a whole variety of different strategies … It’s my privilege to be able to do this work and it’s certainly my pleasure to do this work,” Stein said.

Earlier this year: State announces millions for park accessibility grants

The EEG program was part of a binding agreement in 2000 between Smithfield Foods and the state calling for the hog producer to phase out the use of open-air hog lagoons. As part of that agreement, Smithfield agreed to provide up to $2 million per year for 25 years of environmental projects across the state.

The EEG program began distributing grants in 2002.

Supporter Spotlight

“So far, we’ve done something like 210 projects in excess of $40 million,” Stein said.

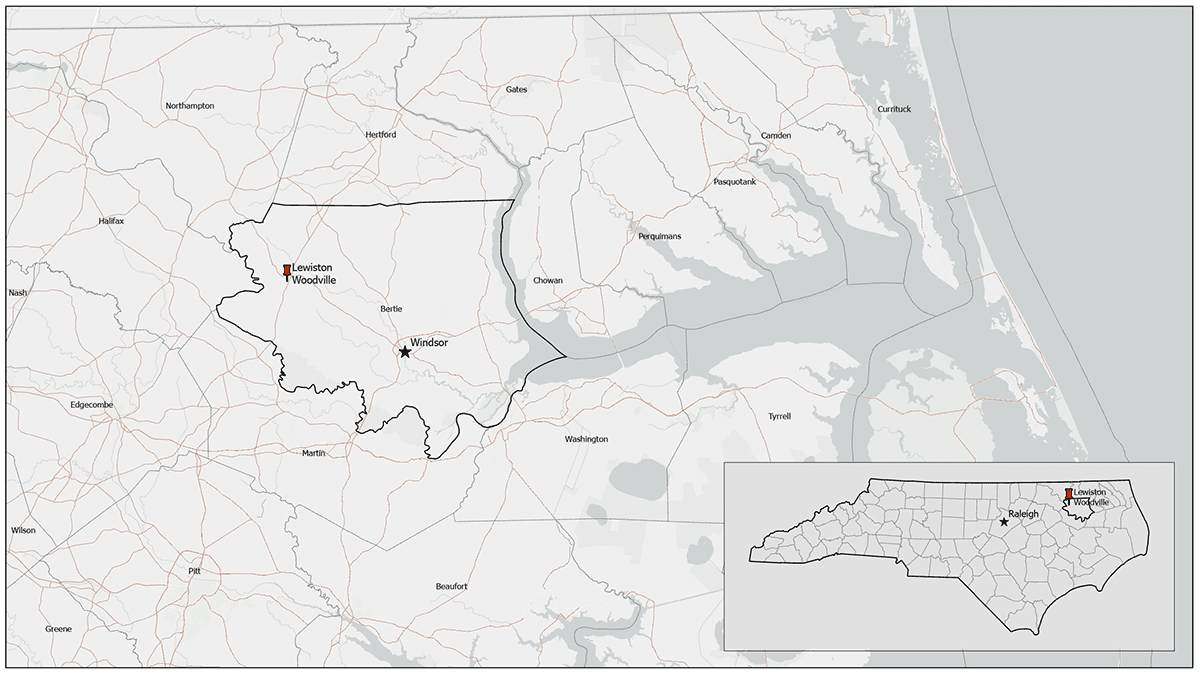

Stein noted in his remarks that most, though not all, of the Environmental Enhancement Grants have been focused on eastern North Carolina, and the grants he came to Bertie County to talk about are specific to the area. The Albemarle Resource Conservation and Development Council received a grant to study algal blooms on the Chowan River, and the Audubon Society is applying a $98,000 grant to wetland restoration in Currituck County.

For many of the grants, the most apparent outcomes are visible. That is the case at Tall Glass of Water, as trails are cleared and much-needed unimpeded access to the beach becomes a reality.

For Bertie County, a Tier 1, or most-distressed county on the North Carolina Department of Commerce’s ranking of counties’ economic well-being, and facing a recent spate of violent crime, six murders this year, at least one of the grants may come to represent the human benefits of environmental enhancements.

The EEG funding for the Bertie County Hive House Virtual Learning Center at 103 Mitchell St. in Lewiston Woodville will create a green space from 4 acres of meadow, overgrown with invasive species and with limited access. But for Vivian Saunders, executive director of the Hive House, the grant, she explained to Stein, is more than just open space for the small town on the west side of the county.

Saunders spoke about “the unfortunate deaths” in Bertie County in the last couple of months, referring to the six homicides in 2023.

“What we’re going to try to do is … get our young people involved in some outdoor workforce-development training so we can get them outside (instead) of playing games and being on video games,” she said. “We’re trying to transform our young people’s minds from sitting in the house staying on video games to being back outside and around nature.”

Saunder’s remarks sparked an almost immediate response from Stein.

“That’s a wonderful articulation of the relationship of kids and mental health and nature,” he said.

Lewiston Woodville was once a small but thriving crossroads town. That was a long time ago. The few businesses that once lined the streets are now closed and falling into disrepair. The only open business by the crossroads is a gas station and convenience store. The paint on the front of the building is chipped and fading. On the west side of town is natural gas infrastructure where maintenance work in May produced a seemingly ceaseless din of venting gas and flame that resembled the sound of a jet engine.

The Bertie County Hive House, at the corner of Mitchell and Cashie streets, is just off the town crossroads. It is a rambling old house that Saunders has made into a gathering place for anyone who wants to come.

The house, Saunders said, was donated to her by her pastor, Dr. Gary Cordon. When she first got it, the house was not in very good shape, but a grant from Perdue Farms, the largest employer in Bertie County, paid for its rehabilitation.

“Perdue, they did the total renovations,” she emphasized.

The Hive House, as Saunders describes it, is a safe place, a shelter where people can come for whatever reason, and she added that space is available at almost any time, day or night.

“If you need somewhere to work, or chill, you can just give me a call: ‘Vivian, can I get into the Hive?’ And my people will come and unlock it,” she said.

For Saunders, the issues confronting the county have their roots in poverty and the hopelessness it creates, and she is uncompromising as she paints a picture of the impact on the county’s youth.

“You’re telling me, sitting in school, that I’ve got the whole world ahead of me. And then I go home, and some folks don’t have toilets. I’m in a mobile home, where I can see the dog running underneath. I don’t have lights on. Sometime my mom and dad are working so hard, I don’t get to see them,” Saunders said describing the county’s poverty.

She points out that the county has one of the state’s highest rates of juvenile diabetes related to obesity, an observation that is confirmed in the 2018 Bertie County Community Health Assessment, and to her the key is getting young adults and kids off social media and back outside.

“We got to get these babies back outside, loving nature, loving the community,” she said. “Kids don’t go outside. They want to be on MacBooks, phones and computers. One of the things that I’m going to require (on the green space work), you’ve got to leave that phone alone. You’ve got to go outside. Our project is to actually build that park.”

The work is still in its earliest stages. The design for the 4-acre green space is being handled by North Carolina State University landscape architecture and environmental planning professor Kofi Boone. He agreed that there is concern about the overall health of the community.

“The health disparities facing Bertie County broadly and Lewiston-Woodville specifically are alarming,” he wrote in an email response to Coastal Review. “That includes all sectors but especially seniors and young people. Vivian Saunders and Hive House have also expressed the need for young people to belong to the process and the transformation and see opportunities to look at workforce development associated with green space transformation.

Asked what the potential impact of creating a community green space could be, Boone was cautiously optimistic.

“The issues facing towns like Lewiston-Woodville are complex and beyond the scope of what one green space can solve on its own,” he wrote. “However, green space that can reflect and reinforce community values can engender a spirit of stewardship and care that can offer safe, and healthy open space for people to enjoy.”

That sense of cautious optimism is shared by Bertie County Sheriff Tyrone Ruffin.

“If people utilize it, yes, it will be a good thing for our county,” he said. “But do I think that is the solution to (all) issues? The answer’s no.”

Boone, however, does see the outdoor space as an important component in addressing the overall health of the community. He noted that the health concerns raised by Saunders could potentially be affected by an outdoor area for the community.

“The town does not currently have a public green space. From research, we know that a lack of access to green space can contribute to a lack of physical activity and poorer health outcomes. We know that well designed green space can help support improved physical health and mental wellbeing,” Boone wrote.

The field is going to take some work to create something usable. There are numerous ways to remove invasive species and Boone has not yet come to a decision on the best method.

“We’re going to be working with a number of partners to determine the right approach to handling invasive species. The treatments can vary,” he wrote.

There is also, evidently, material from what was once the West Bertie Elementary School that closed in the 1970s, according to Boone.

Graduate students from the N.C. State School of Landscape Architecture will be on hand to supervise the work, at times spending the night at the Hive House. Saunders mentioned that they are donating their time, and that the only request they made was, “all they’ve asked us to do is keep the fridge full for us.”

The project is still in its earliest stages, yet for Saunders even as the initial steps are taken, she sees hope in the willingness of people to work together to improve conditions in a troubled county.

“I want to thank everyone involved in helping us transform and take back our county from all the negativity that’s been going on,” she said.

Next in the series: A Tall Glass of Water.