DUCK — Two women scientists, longtime remote co-workers, recently met on the Outer Banks to celebrate the new annex at the renowned U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Field Research Facility, better known as the Duck Pier.

But their roles and rank among the nation’s premier military and civilian scientists is a notable achievement in their own right.

Supporter Spotlight

“We are now 50-50 men and women,” Katherine “Kate” Brodie, senior technical manager and senior research oceanographer at the facility’s Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory, said during a tour of the annex in January, referring to the pier’s science and engineering staff. “Which I think is a really great accomplishment for women.”

The $4.3-million annex consists of laboratory and research administrative spaces in support of the organization’s expanded military research mission.

Standing alongside Brodie in the annex’s secure room, Mihan McKenna Taylor, senior scientist at the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg, Mississippi, noted pointedly that the nearby lactation room illustrates progress women have made in the workforce. “The closets are no fun,” she said, recalling the only quiet spaces once available for staff to nurse babies.

As fellow scientists employed by ERDC, Brodie and McKenna Taylor’s careers exemplify not only how women can excel as engineers, software technicians and physicists, but also the importance of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, role models for girls.

Only about 11% of teen girls plan to pursue STEM careers, compared with 35% of boys, according to the American Association of University Women. Although women make up about 28% of the STEM workforce, the gender gap is widest in the fastest-growing and most highly paid fields: 16.5% in engineering and architects and 25.2% in computer and math, according to the National Girls Collaborative Project.

Supporter Spotlight

Brodie, who graduated from Dartmouth College before earning her doctorate from William and Mary School of Marine Science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, focused on geological or geophysical oceanography. In her role today as technical manager at the Duck Pier, she helps develop and manage ongoing and future research, as well as mentor early career researchers.

A National Science Foundation fellowship in the summer before her senior year at Dartmouth changed her interest from Earth science to marine science. One of the projects involved working on a model that used current data from radar antenna in Chesapeake Bay to forecast where a person who fell in the water would be located, based on the currents. That was when she learned to code and to see the relationship between math and the dynamics of physics.

“I left that internship feeling really excited and saying, ‘I want to go to graduate school and do oceanography.’” Ultimately, Brodie learned the coding skills that gave her a big leg up in the field of marine sciences, which don’t typically require strong math and computer science or programming skill sets.

“And I think they 100% should be because in the job that I do today, that is all I am doing,” she said. “You need to understand the physics, you need to understand the oceanography, but to do anything with that data, you need to be able to code and you need to understand the math.”

Early on, Brodie, whose expertise is in using remote-sensing observation equipment to collect real-time data in the surf zone, said she was inspired by McKenna Taylor.

“When I started at the FRF (Field Research Facility) itself, I was one of two women on the science and engineering staff, and the only other woman at the facility was our administrative support at the time,” Brodie said in a recent interview, recalling when she began her job right out of graduate school in June 2010. “I was the youngest by probably about 10 years. And so, I think, at that time, there was not a lot of equality.”

Brodie’s collaborative work often required her to visit ERDC’s main laboratories in Vicksburg.

“I would walk into many rooms where I was the only woman and I think the exception to that was probably the first time I met Mihan,” she recalled. Even back then, before McKenna Taylor was a senior scientist, Brodie said, she was presenting her research with “such a presence and with such personality.”

“I just thought it was so cool that there was this really accomplished woman scientist who was commanding the room — it was definitely male-dominated,” Brodie said. “That really, really struck me as a young woman scientist … particularly in the field of coastal science and engineering.”

Still, over the years, Brodie said, the number of women coastal scientists has grown, and she has met numerous accomplished women researchers, engineers and academics at numerous conferences and events where she has attended.

In time, Brodie, too, was considered one of those very accomplished female scientists. Slender, with blond hair and a casual style, Brodie could be mistaken for a college student. Although she’s not flashy about her brain power, her ease and clarity in explaining the technology and science at the Duck Pier makes it clear why she has a senior position.

Young women graduate students started approaching her at conferences, which led to those young women doing internships at the Duck Pier, and later being hired there. So before long, the pier’s technical staff was half women.

“You know, I didn’t actively have the goal of creating a science staff here at the FRF that was 50-50 split, women and men,” Brodie said. “And so, I think in some ways that’s also impressive that we ended up there without actively selecting for it.”

The 176-acre Duck Pier, which opened in 1977, is ERDC’s only coastal field observation facility. With its 1,840-foot steel and concrete pier and 140-foot-high observation tower, it is ERDC’s only location that conducts continuous observations and collects extensive and detailed data on coastal processes.

In collaboration with the Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence, the new 4,008-square-foot annex is focused on research in developing methods to protect and inform military forces, especially operations in the littoral, or nearshore, coastal areas.

As Brodie put it during the Duck Pier tour: “I want to digitalize a surfer’s brain.”

Surfers are experts at reading real-time beach conditions and figuring out how to navigate them safely to achieve their goal, which is wave riding. For the military, the goal is getting personnel and vessels through the surf zone without tipping or other mishaps.

One of Brodie’s first assignments at the Field Research Facility was a more military-funded project that studied how remote-sensing technology could be used to assess a coastline. In other words, how can technology replicate in real time the information a surfer collects and interprets when looking at the waves and currents?

It turns out that the years of civil works research at the Duck Pier as well as its unique instrumentation and techniques developed for its observations and models, Brodie said, were assets to the evolving needs of the military.

“We were well-poised to transition those to help the warfighter with their recent focus and shift toward littoral environments,” she said in the later interview.

Starting with imagery collected from unmanned aerial systems and using Duck Pier instruments, over time Brodie and the ERDC team developed integrated sensing. The technology incorporated relevant data collected from LiDAR scans of a beach, satellites, buoys and towers that recorded information about waves, currents, winds and other factors that influenced the nearshore. Now the software is being readied to make the leap from the research and development pipeline to production.

With the success of the “surfers’ brain” software, funding for the research grew, and the Department of Defense mission expanded to support not only the Army but also Navy and Marine operations.

“So I would say that that initial project, we’ve been able to grow that and show the value of the technology that we were developing,” Brodie elaborated. “I think if you think about the current sort of climate that we are in, in the world right now, and thinking about where some of the next future conflicts may be, a lot of those locations may involve needing to cross through the littorals or through coasts in some capacity. And so I think there’s been a shift DoD-wide to focus back on the littorals, away from desert environments where the Army has really been focused for the last 20 years.”

Over at ERDC headquarters in Vicksburg, McKenna Taylor oversees a scientific discipline called “near service phenomenology,” or the study of the interface of air, land and sea with the human domain, and a specialty in terrain assessment and manipulation. If it’s a tunnel, a bridge, a building or other things that humans manipulate within the Army’s research domain in the water, the air and the land, it’s probably part of Taylor’s expertise. That would include sensing technologies, most geophysically based, such as infrasound, hydroacoustics and seismology.

“We’re considered long-term strategic thinkers. It takes 15 to 17 years to field any technology that started from embryonic conception, all the way out to warfighter usage in the way our acquisition and fielding works in the Army now,” she said in a later interview. “I’ve taken a wild and crazy idea from basic research in 2005, and it was fielded with engineers or fighters in 2021.”

Like Brodie, McKenna Taylor started at ERDC right out of graduate school, except she began as a research geophysicist in 2005. With an undergraduate degree from Georgetown University in Washington — a major in physics, a minor in chemistry and an unofficial minor in music — she earned her doctorate in geophysics from Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Her visit to the Duck Pier was her first in a professional capacity, but she had often come with her family to the Outer Banks from Greensboro, where she grew up.

McKenna Taylor said she was always good at math, but a seventh grade National Science Foundation physics camp had a big impact on her future career choice. At Georgetown, she said, there were typically “two women and 12 dudes.” But the year she studied physics, it was the opposite. Turns out that other women had also attended summer physics camp.

After earning her doctorate, she resisted the siren song of the oil and gas industry, a job many with her education were offered.

“It was super not for me,” she said. “I wanted to make a difference, not make money. And the bottom line in oil and gas is the bottom line.”

The Corps’ research and development branch, which is funded by sponsors and not by Congress, offered her a flexibility to be creative and have a family life, while still being part of a team focused on the national good.

“And that kind of combination really appealed to me,” she said. “It’s fun. You know, you can change what you do five times a week or every five years. Depending on what you are investing your time in. And if you’re the sort of researcher that loves the challenge and likes to create your own vision, it’s phenomenal.”

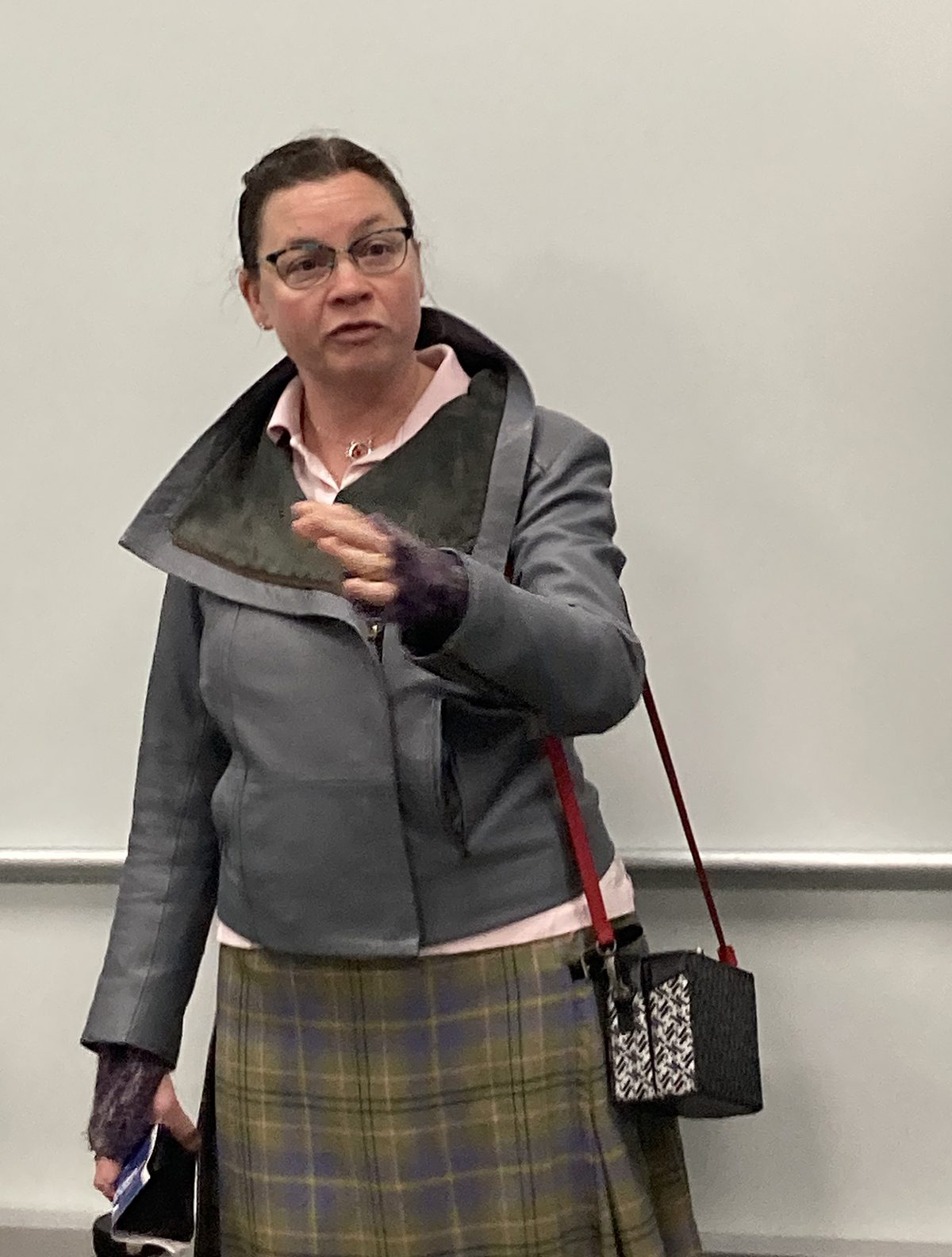

If there is a stereotype of a woman scientist, McKenna Taylor is not it. She acknowledges being opinionated and assertive: “There’s a lot of blowback to it. I fundamentally don’t care.” When she attended the event at the Duck Pier, she was dressed in a full-length purple, pink and lime-green Scottish kilt, a gift from her husband. She talks exceptionally quickly, barely pausing while explaining complex science and head-spinning levels of government within ERDC and the DoD. At the same time, she is open, self-depreciating and funny.

She also plays viola, violin and string bass.

“Right now, I play in a band, I play in an orchestra, I play in a wedding quartet,” she said, matter-of-factly. “I like to think of it this way: Physics is just the music the universe makes. The music the universe makes that we can write down in a different language is the mathematics of physics, or geophysics, specifically. So to me, they’re not different. They’re just a different expression of the same language and feeling and perspective on the world.”

As a mother of two boys, McKenna Taylor has had to navigate the same stressors as other women around childcare and the demands of parenting, especially prior to when federal parental leave was provided. But as a team leader at ERDC, with her supervisors’ support, she deliberately approached work with the belief that fathers and mothers deserve a “whole life balance” that supports family life as well as work.

“It’s important to have a whole life,” she said. “And what that means to each person is very different. But if you have someone who feels satisfied with their whole life balance, they work their tails off. They feel invested.

“I firmly do not believe you can have it all,” she continued. “But you can make choices to have the parts of you that need to be satisfied to exist as a human. Those choices should be yours to make and they should be options.”

But there’s a lot more than that balance that will bring more women physicists and engineers into the workforce,” McKenna Taylor said. The education system needs to be more hands-on. It needs to allow girls to experience the adventure in research. It needs to empower students to have the freedom to fail — “It’s how we learn,” she said — and it needs to let students blow things up.

“I think we need a revitalization of the importance of good, solid, critical thinking and scientific education, from starting people in prekindergarten all the way up through advanced degrees, the respect that science needs to regain,” she said. “You get talking heads that denigrate expertise, and that handicaps us as a country, because if you can’t strive for excellence, what do you become?”