Carp removal. Sedimentation reduction. Regrowth of underwater vegetation.

Years of cooperative groundwork between individuals and agencies will soon translate into visible projects to restore Lake Mattamuskeet’s water quality.

Supporter Spotlight

And that, in turn, could benefit all area residents — human and wildlife.

Located on the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula, Lake Mattamuskeet covers about 40,000 acres and is the largest natural lake in North Carolina. County residents point to the lake as the center of Hyde County, both geographically and culturally.

Related: Inner coast: Lake Mattamuskeet draws outdoor enthusiasts

Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1934, comprises the lake and 10,000 acres of surrounding land. It’s an important overwintering site for migratory waterfowl along the Atlantic Flyway and a year-round habitat for many other species. The county is known as a hunting, fishing and bird-watching destination and for its rich farmland.

Hyde County, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission contracted with the North Carolina Coastal Federation, publisher of Coastal Review, to develop the nearly 200-page Lake Mattamuskeet Watershed Restoration Plan, which was finalized in 2018 and approved by the state in 2019.

Supporter Spotlight

The plan names three interconnected goals: To protect the current way of life; to actively manage the lake’s water level; and to restore the lake’s water quality and clarity.

The plan was developed with input from a stakeholder team that included area residents, local government officials, graduate students, university professors, refuge staff and the Mattamuskeet Technical Working Group, a joint effort between Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

“Everyone wants to see that lake cleaned up,” said Wendy Stanton, technical working group co-chair and acting refuge manager for Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Columbia.

Stanton called the lake “out of balance,” explaining that everyone is “trying to restore that balance” so it can again become “a healthy aquatic ecosystem.”

After about six years of the team meeting to address the problem from various angles, “it’s encouraging that their stamina and enthusiasm for the effort is still there. That speaks volumes to the care and concern and love that everybody has for this lake,” said Erin Fleckenstein, oyster program director for the Coastal Federation. She helped coordinate the development of the watershed restoration plan.

“Most local stakeholders have very fond memories of boating, fishing and crabbing on the lake. It’s part of their history, as well as their community’s history,” she continued.

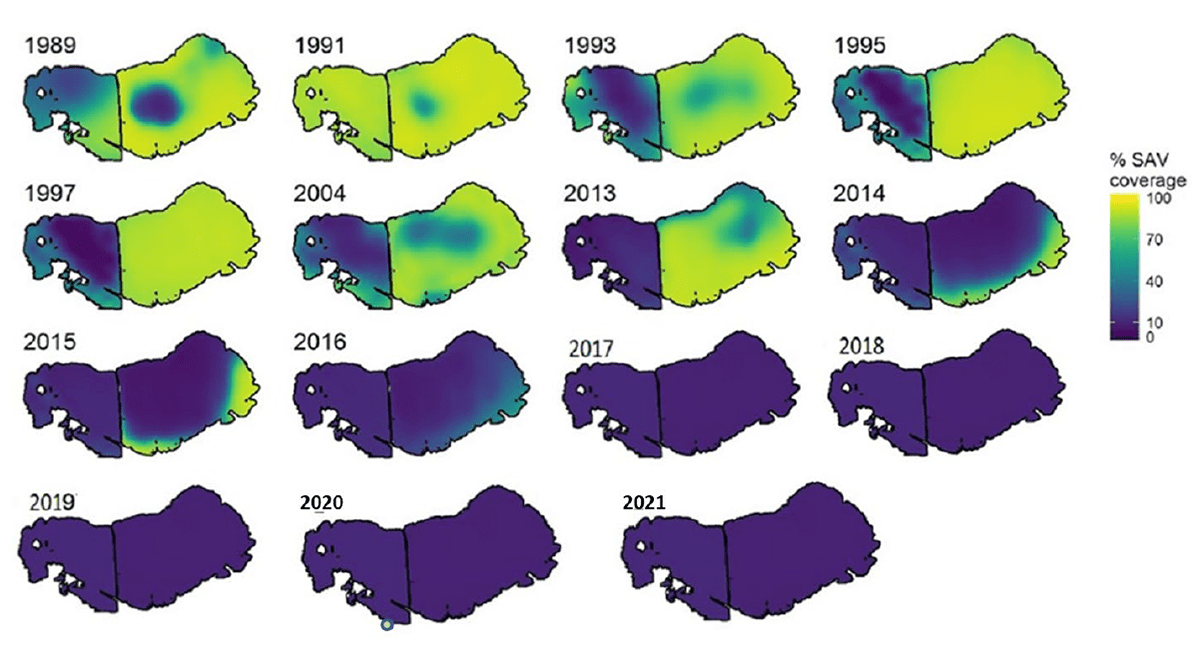

Officials involved in the restoration efforts point to the growth of submerged aquatic vegetation, also called SAV or seagrass, as both a main goal and as an indicator of success.

Monitoring by the Fish and Wildlife Service initially noted seagrass declines in the late 1980s. By 2017, no plants could be found during the refuge’s annual SAV survey.

For aquatic plant life to return, two actions are required, according to Stanton: carp removal and the reduction of sediments being put into the lake.

The restoration plan calls for the removal of 5 million pounds of invasive common carp from the lake. Each adult fish weighs 4 to 5 pounds, Stanton said. Carp are bottom feeders, and their rooting for food also results in ripping up vegetation.

Human activities also must change. Fertilizer, fossil fuels, wastewater, stormwater and pet manure can cause “nutrient pollution” — excess nitrogen and phosphorus — in nearby waters, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

These sediments reduce water clarity, blocking sunlight from reaching the bottom, and aquatic vegetation cannot grow without sunlight, officials note on the agency’s website.

The overabundance of suspended nitrogen and phosphorus solids in Lake Mattamuskeet also contributes to blooms of phytoplankton and cyanobacteria, which “outcompete SAV,” according to the Fish and Wildlife Service website.

Cyanobacteria’s adverse effects extend beyond harming plant life.

As a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “Harmful Algal Bloom Advisory” sign posted near a Lake Mattamuskeet culvert notes, “Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) can produce toxins that can cause serious illness in animals and humans.”

Lake Mattamuskeet is currently considered a phytoplankton-cyanobacteria-dominated system. Once the shift from an aquatic plant-dominated system to an algae-dominated one like this occurs, “it takes a lot of work to return the system,” said Kelly Davis, who owns land adjacent to the lake and worked as the longtime refuge biologist.

She’s implementing a water-control project on her property to change the direction of runoff from her farmland. Instead of allowing gravity to carry runoff, which invariably includes some sediment, to the lake, she’s diverting it to the woodland area of her property.

Davis acknowledged that her actions alone will not clean the lake, but putting water management on her farm is one of many positive steps that area residents are taking.

“You take little bites of a big problem,” Davis stated. “It’s exciting to be working toward improving it.”

Davis’ project was already being designed prior to the restoration plan’s development, but that plan may involve similar water-control projects on other properties.

Although not yet finalized, one involves replumbing a private landowner’s drainage to move through restored wetlands instead of discharging into coastal waters, Fleckenstein said. Smaller projects with individual landowners like these may eventually serve as models for others in the county or in the 55,000-acre watershed, she added.

Larger-scale projects are being developed simultaneously. The Coastal Federation has worked on behalf of the county to help orchestrate some engineering, surveying and permitting work on those, Fleckenstein said. Multiple grants are involved in work toward the plan goals.

Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge already has been working on better water quality control in its waterfowl impoundments, which are areas managed specifically for waterfowl, according to Stanton.

For any such effort, large-scale or small-scale, the key is to slow down the movement of water draining into the lake, so sediment has time to settle and not as much enters the lake, Davis explained.

Another necessary task is regularly clearing excess sediment from the four main canals that link the lake to the Pamlico Sound. The lake’s water level has been passively managed by the wind since the canals were built with one-way gates allowing drainage into the sound, Davis said.

As the restoration plan document states: “Rising sea levels and siltation of the main canals connecting the lake to the Pamlico Sound are thought to be contributing factors in the decline of drainage function, and those conditions are anticipated to exacerbate flooding in the future.”

And when the surrounding land floods, landowners sometimes use pumps to push the water off their properties. That accelerated velocity gives sediment less of a chance to fall out of the water before it ends up back in the lake, Davis noted.

But with the widespread support of the community, the restoration plan will disrupt that negative chain reaction.

Some changes are already underway.

Signs are going up at each of the five culverts that run beneath N.C. Highway 94 and connect the east and west sides of the lake warning of possible temporary closures for recreational fishing when carp removal efforts begin, Stanton said.

And that could be soon.

“We expect to receive that money any day now,” Stanton said on Feb. 24 of a $1 million large invasive species grant the Fish and Wildlife Service awarded the technical working group.

As soon as the money is available, the group will publicize the contract and accept bids. She estimates most carp will be removed within the next two years.

“Whoever the vendor is, they get to keep the carp,” she said. “They can dispose of them or use the various markets as they see fit.”

Carp are in demand as a food source in markets in New York and elsewhere, Stanton noted. Another option might be stocking catch-and-release fishing ponds on the western side of the state. When a prior, effective, large-scale carp removal program took place at the lake in the 1940s and 1950s, that is where most carp ended up, Stanton said.

Other steps have already been taken to address the carp problem. Barriers were installed at the tide gates in March 2021. Flat metal bars two inches apart prevent adult carp from entering the lake, while still allowing native fish species and blue crabs to pass back and forth from the sound, Stanton said.

This will also be the third year that the state Wildlife Resources Commission has stocked the lake with bluegills, a native fish species known for its voracious appetite for carp eggs and carp larvae, around the mid-May carp spawning season.

“A lot of people like fishing bluegills, too, so it not only helps us reduce the carp, but also provides recreational fishing opportunities,” Stanton noted.

For more information about the restoration projects, visit www.fws.gov/project/lake-mattamuskeet-aquatic-grass-restoration and www.nccoast.org/protect-the-coast/stormwater/lake-mattamuskeet-watershed-restoration/.