To help a coastal conservation organization learn more about the kind of debris littering southeastern shorelines, around 40 citizen scientists collected over 2,000 samples of microplastics between May and October of last year.

The samples of microplastics, which are tiny pieces of fishing line, bottles, balloons, takeout containers and other plastics measuring less than 5 millimeters, were gathered from more than a dozen sites on the sound and beach between North Topsail Beach and Sunset Beach.

Supporter Spotlight

The volunteers recorded their findings for the North Carolina Coastal Federation-led report, “Microplastics in Southeastern North Carolina: A monitoring and recommendations report” released in late January.

The report was motivated by the amount of microplastics found during the many large-scale cleanups that the Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, had organized after Hurricane Florence caused immense damage in 2018, especially to docks and piers.

Report results point to the unencapsulated polystyrene, or foam, used in pier and dock construction contributing a significant amount of microplastics in those waters.

Volunteers collected 295 sample sets that they categorized into the five microplastics categories. In total, they collected 252 fragments of rigid plastics and firm, brittle pieces; 163 pellets, or plastic beads; 221 pieces of fishing line or plastic rope; 88 films such as balloons and shopping bags; and 1,418 pieces of foam, according to the report.

In addition to microplastics, volunteers found pieces of plastic bottles like caps and labels, cigarette butts, plastic utensils, and large fragments of foam.

Supporter Spotlight

Federation Coastal Specialist Georgia Busch told Coastal Review that the results were unsurprising, considering that type of microplastic was the impetus for the citizen-science project.

What did come to light during the sampling period, she added, is that the volunteers with access to marshes, sounds and waterways found more and diverse microplastics in those locations versus on beaches. The tiny foam pieces seemed to accumulate and last a bit longer soundside as compared to the oceanfront.

The concern with microplastics is that they are a type of plastic pollution, and all kinds of plastic waste can break down into microplastics that will persist forever, Busch explained. Microplastics don’t belong in the ecosystem, are impacting all levels of the food web, and are a risk to human health through eating anything sourced from the ocean.

About a third of the seafood species consumed in North Carolina currently do and will consistently have traces of microplastics in them, Busch said. While that doesn’t necessarily mean that your filet is going to be covered in plastic, there’s a toxicity level to be concerned about.

Busch said that the citizen-science project is a continuation of the Coastal Federation’s work to recover marine debris after Hurricane Florence in estuaries and wetlands.

During the Hurricane Florence recovery project that has taken place over the last few years, 85% of the debris the field crews collected in marshes was from damaged residential docks and piers.

“One of the common main components for a floating dock of that type is a big polystyrene brick,” Busch said. This material is typically unencapsulated, or not protected with an outer cover to prevent the polystyrene from breaking down in the elements into tiny foam beads. These pieces eventually break down small enough to be considered microplastics.

Though the field crews were not looking for microplastics during the large-scale cleanups, they did find evidence of the polystyrene breaking down. This citizen-science effort with longtime Coastal Federation volunteers — and new ones — provided quantitative data to support the hypothesis that microplastics can come from larger-scale debris.

Wilmington-based Boy Scout Brooks Ford reached out to the Coastal Federation with the idea to follow the Environmental Protection Agency’s protocol to sample microplastics in area beaches for his Eagle Scout project, Busch said.

The EPA’s “Microplastic Beach Protocol” was designed for citizen scientists to collect data on microplastic pollution on marine beaches and shorelines to determine local, regional and global marine debris trends, according to the report.

Ford is in Troop 234, chartered by Wesleyan Chapel United Methodist Church in Wilmington, and currently a sophomore in high school. He completed the project in spring 2022 while still a freshman.

With sponsorship from area hardware stores, restaurants and supporters, he was able to provide 24 microplastics collection kits for the volunteers to use. The kits were designed and the sieves handmade using EPA guidelines. Ford, with help from his troop, worked on the project for six months.

“In scouting, I have been taught to leave no trace,” Ford said in an email response for comment about why he chose this project.

“While we enjoy nature and the great outdoors while hiking, camping, and participating in recreational activities, we must also respect wildlife and the environment. This project gave me an opportunity to learn how our heavy use and disposal of plastics negatively affects our environment, specifically the coastline I have the privilege of enjoying,” he said. “As a Boy Scout, I feel I have a lifelong duty to educate, model, and advocate for environmentally sustainable practices. Working with the North Carolina Coastal Federation to complete my Eagle Scout project opened my eyes to a new world of understanding the need to restore and protect the natural habitats of our coast.”

With Ford’s effort and knowing what crews found during the large-scale cleanups, Busch said that they were encouraged to assess on a smaller scale how microplastics are impacting area beaches.

During the six-month collection season last year, volunteers would head out weekly with their kits made up of 5-gallon buckets, hand shovels, brushes and 5-millimeter mesh to sift microplastics out of the sand. They’d work a 10-square-foot space somewhere between the wet sand and the high-tide line.

Then, the volunteers would record what they found, the time of collection and how busy the beach was, what the weather was like and the status of the tide and submit that information to Busch. She said that there were some days when volunteers would find very few samples, but that depended on where they were working.

Elise Snavely is among the dozens of volunteers who helped with the project.

Originally from Martinsville, Virginia, Snavely said in an interview that she has a background in marine ecology and wanted to become more involved with the Coastal Federation. She earned a bachelor’s from University of North Carolina Wilmington in 2019 and a master’s in biodiversity and conservation at the University of Ghent in Belgium in 2016.

“I was initially asked to get involved in the microplastics sampling back in the spring, but wasn’t able to commit to the weekly sampling then. But in the summer, I met another volunteer, Dennis Doll, at a Coastal Ambassador meeting and he invited me to go sampling with himself and his sampling buddy, Sue-Ann Rush out at Fort Caswell. I had a blast and was told it was nice to have a set of ‘young eyes’ around for the sorting so I ended up going several more times through the summer and fall,” Snavely said. Coastal Ambassadors is a program for Coastal Federation volunteers.

While much of her past sampling work has been in marshes and mangroves, she never sampled on the beach.

“It was a really nice change! Barefoot sampling with no risk of stepping on oysters is something I could get used to. Keeping the tiny plastic pieces we uncovered from blowing away once the sand was sifted out was a bit challenging,” she said.

One challenge, Snavely said, is that it was occasionally really difficult to tell small pieces of plastic from organic matter.

“There was one week when there was some sort of worm casing or egg sack all over the beach, they looked and moved a lot like the plastic films or straw wrappers we had found previously,” she said. “I still don’t know what they were, but we ended up consulting Georgia (Busch) because we just weren’t sure when we were on the beach sampling. The thing that surprised me the most though, was that we didn’t find more plastics. Our sampling location was right at the mouth of the Cape Fear, I was surprised there wasn’t more plastic deposition there.”

Busch said that one of the goals behind the report is to keep those interested up to date on what the Coastal Federation is physically finding and any advocacy or recommendations developed as a result.

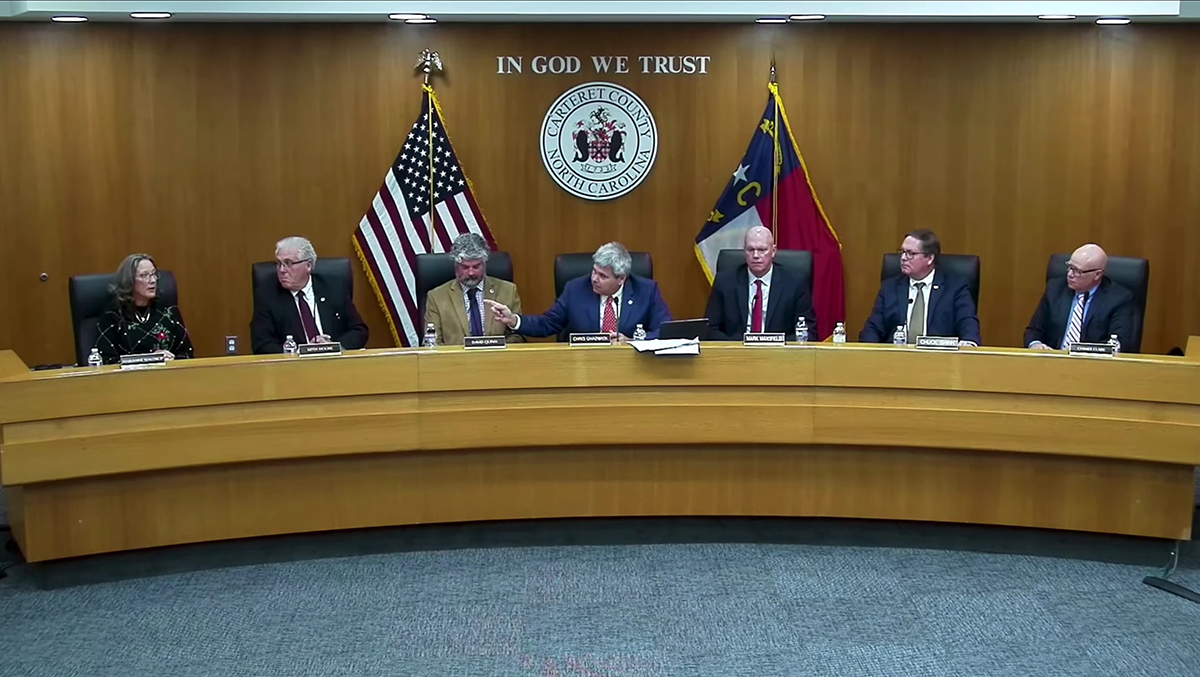

Busch encouraged residents concerned about microplastics in their community to speak to their elected officials and local governments.

A few local governments already have taken steps to eliminate microplastics resulting from damaged residential docks and piers in the region. North Topsail Beach, Surf City, Topsail Beach and Wrightsville Beach have passed ordinances prohibiting the use of unencapsulated polystyrene as structural components for any new floating docks.

“That’s a huge win for us,” she added.

Contact Busch at georgiab@nccoast.org or 910-509-2838 ext. 206 to learn more about the report, the sampling program or information on ordinances to prevent microplastics pollution.