WANCHESE – The federal government recently announced new offshore wind energy lease areas off the North Carolina coast, but for Dr. Mike Muglia, assistant director for science and research with the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Program at the Coastal Studies Institute, there is tremendous additional potential for power generation in the ocean’s waters.

Much of Muglia’s research focus has been on how ocean currents can be harnessed, and he said the potential is huge, and while the obstacles are big too, the Gulf Stream could be the largest single focused source of renewable energy identified to date.

Supporter Spotlight

“That’s all the water in the Atlantic Ocean that’s flowing north on the surface layer,” explained Muglia, who spoke during a recent Science on the Sound lecture. “Drive the rest of the way across the Atlantic Ocean and the water’s coming back south. You’re moving about 30 times the flow of all the rivers on Earth off Cape Hatteras in the Gulf Stream, an immense amount of energy and volume of water.”

The monthly lecture series at the Coastal Studies Institute on the East Carolina University Outer Banks Campus examines coastal topics and issues relevant to the state’s northern coast. Each lecture is also livestreamed and archived on the institute’s YouTube channel.

Standing in front of a map showing the confluence of the Gulf Stream, Labrador Current and the boundary waters, Muglia said the Outer Banks is an outstanding location for ocean studies.

“We happen to live in one of the best places in the world for oceanography and the coolest, most exciting place ever,” Muglia said. “We have this huge confluence of all these different water masses occurring right off of Cape Hatteras in our backyard.”

There is an extraordinary amount of energy in those water masses, he said, and ocean energy in general is a resource of almost extraordinary potential that could represent a significant third renewable energy resource joining wind and solar. But the technology is still in its infancy, Muglia noted.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s a pretty new industry, which is why it’s not necessarily cost-competitive with wind and solar that have been around for 50 or 100 years,” he said.

Research to bring down the cost of generating ocean energy is moving forward. One of the advantages ocean energy offers is the range of options.

Muglia said it appears straightforward, but it’s not that simple.

“I’m a physics guy. I work with engineers, and we all think the same, which means, ‘All right, let’s see how much we have out there. Where’s the best wave resource? Where should we go put this thing and then how can we build something to get that energy?’ We think that’s all there is to get energy. And that’s totally wrong,” he said.

A big obstacle is developing mechanisms to capture and convert ocean energy and transmit it to the power grid.

“This is a really new endeavor,” he said. “There aren’t people building wave energy converters. We need to bring those people up to speed on what we’re actually doing and teach them, and then they’ll surpass us. “

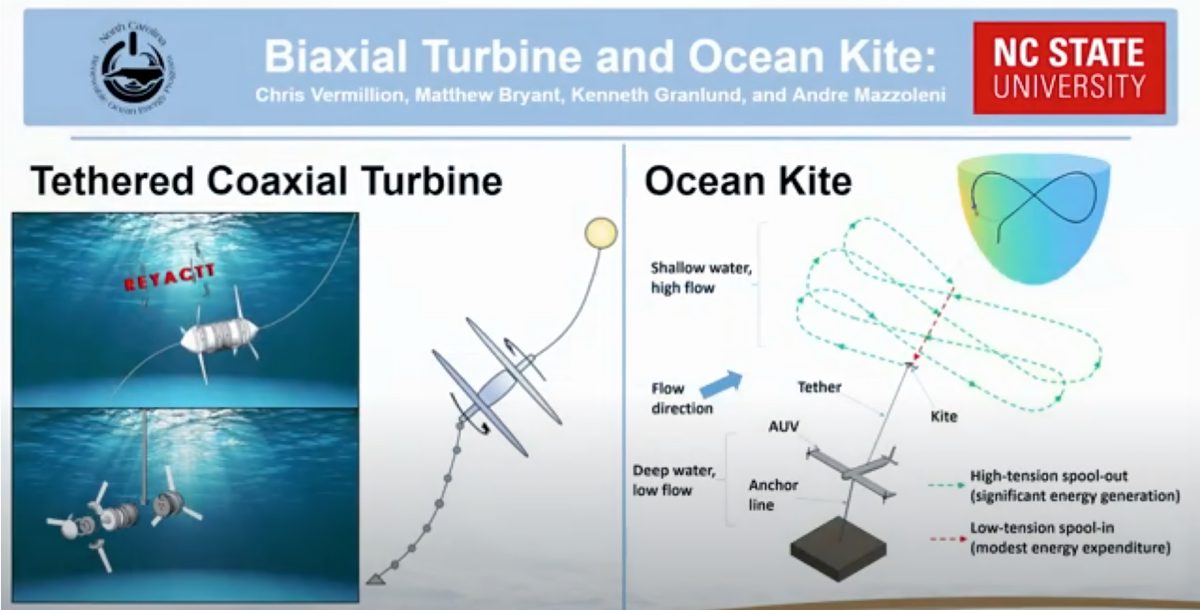

If grid-level ocean energy production is still years in the future, there are already smaller devices that Muglia is working on that may have commercial application. Two devices in particular, a tethered coaxial turbine and an ocean kite may have commercial potential, and prototypes are being tested.

Developed by a North Carolina State University team, the coaxial turbine looks like a torpedo that is tapered at both tips. It features two rotors, one at each end. When deployed, the turbine will be tethered and operate at an angle — yawed — to the current. The rotors counterrotate to eliminate the torque that would occur if both rotors were to turn in the same direction.

“The reason that it’s yawed is that you can get fresh flow on both rotors,” Muglia said. “If you had a line with the current the second rotor would be in the turbulence of the first. This way it gets clean flow on both rotors.”

The device was recently tested at Lake Norman, a hydroelectric dam reservoir that covers nearly 1,800 square miles, where it was towed behind a boat to simulate an ocean current.

“Lake Norman has these long fetches of very deep water where we can tow for a long time and simulate the current on them,” Muglia said, explaining why the devices were tested at that location.

The Lake Norman prototype was equipped with a generator. The next deployment of the coaxial turbine is planned to take place in waters near the Coastal Studies Institute and will test the device’s ability to desalinate the water.

“The one we’re going to test in our backyard has a pump, so it can do reverse osmosis by pumping water from the device up the line to a reverse-osmosis system,” Muglia said.

The other device, the underwater kite, may be closer to actual application than the coaxial turbine, although it’s not clear whether the public will be seeing it in use any time soon.

With primary design work done by Chris Vermillion at NC State, the Ocean Kite System for Marine Hydrokinetic Energy Harvesting, as it is officially known, will move through the water in in a figure-eight motion, collecting and transmitting energy along its tether.

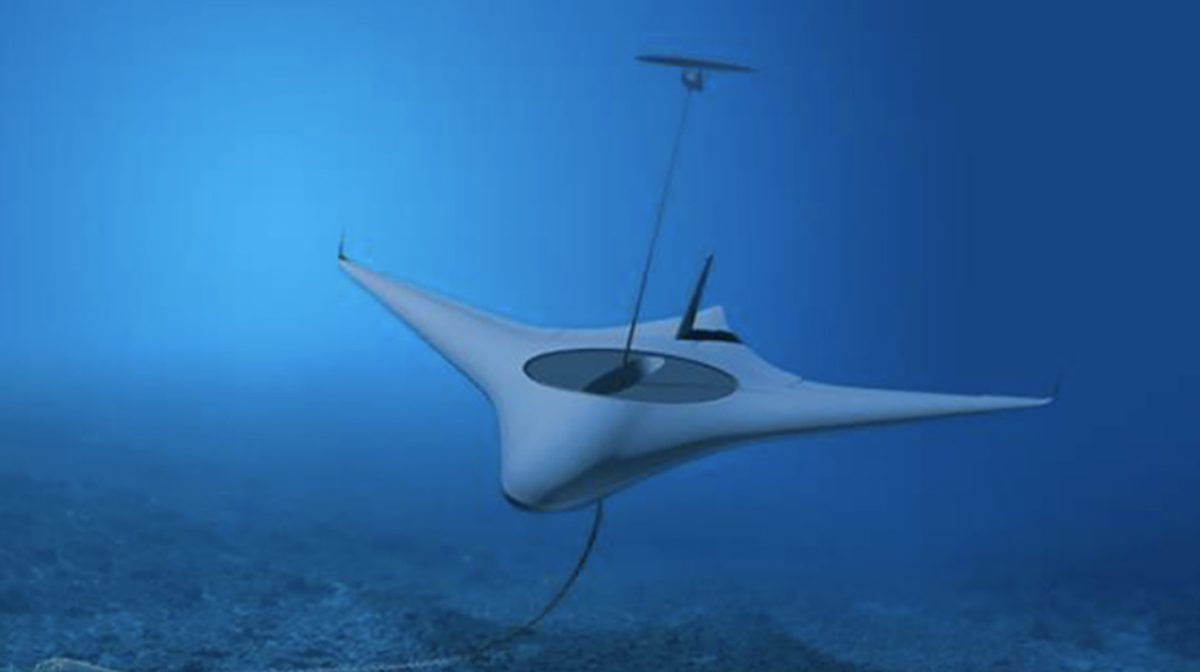

The ocean kite may be the first of the ocean current-harvesting systems to be deployed. Muglia explained that the kite is part of a project for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, which is looking for ways to power an unmanned submarine. The submarine, called the Manta Ray, is designed for stealth movement and minimal drag as it maneuvers beneath the surface.

Desalination technology

Although much of the research Muglia described is focused on how to harness the ocean’s power for energy production, there are other areas of research that use wave action without necessarily generating or storing electricity.

Waves to Water, held at Jennette’s Pier in April, was a National Renewable Energy Lab-sponsored competition calling for relatively lightweight, easily assembled systems that can produce clean drinking water using only wave energy. The lab’s overview described the devices as, “small, modular, wave-powered desalination systems capable of providing potable drinking water in disaster relief scenarios and remote coastal locations.”

Muglia and his team at the Coastal Studies Institute organized the deployment of the four systems during the competition, and all produced fresh water. The winning entry, from Canadian company Oneka Technologies, was able to produce 1,000 liters of water per day.

What may be most remarkable though, is the Oneka system used only the power of the waves to pump water through a membrane. There was no electric-powered pump onboard.

“This device pressurizes water and forces it through a semi permeable membrane so it’s not making electricity,” Muglia explained. “It’s just using this giant device as a pump. And when Trip (Taylor, a research assistant at the institute) got on this to activate it. He said it was incredible because as soon as a little wave hit it, it was like these big lungs just going and just pumping.”

While the applications of ocean energy are still in their infancy, especially for generating power to light homes and businesses, George Bonner, director of the Renewable Ocean Energy Program, has been pushing the microgrid possibilities of ocean energy since he joined the institute in 2019.

Muglia, responding to a question about that technology, expressed support for his colleague’s goal.

“Ultimately, what we’d like to do is to take the energy that we’re getting from these devices and put them in charging stations for cars in the parking lot. That’s what George is hellbent to do and we’re all with him.”