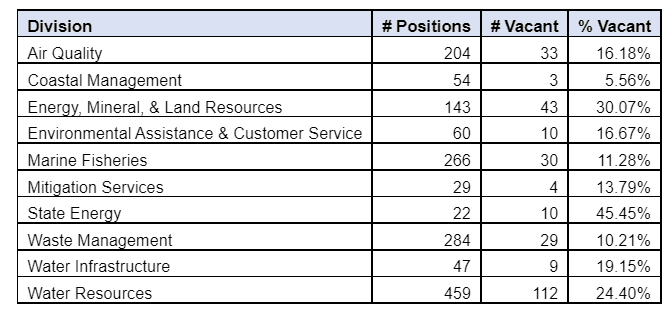

Nearly one-fifth of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s job positions are unfilled, leaving the agency responsible for administering regulations to protect water, air quality and the public’s health in a tight pinch that is not likely to loosen any time soon.

As of Oct. 25, 19.19% — 340 of 1,772 positions — in DEQ were vacant. That includes new, time-limited positions created to administer federal funding programs, according to information provided by a DEQ official.

Supporter Spotlight

DEQ’s staffing shortage is indicative of a broader issue in state government, where a number of departments are dealing with even steeper declines, putting the squeeze on state employees who are left to pick up the slack while typically making less than their professional counterparts in the private sector.

State government job vacancies were up more than 22% by the end of August.

The employee void is hitting every state government sector from public schools to safety to health and human services, all while billions of dollars are tucked away, unappropriated, in reserve accounts.

Unless legislators pump some of those funds to state agencies to ensure employees are paid at rates competitive with the private sector, unfilled job positions may rise, deepening a void that is already being felt by those the government is here to serve – you.

Tough competition

Compounding the loss of staff to higher-paying private sector jobs is the number of retirement-eligible staff within the department.

Supporter Spotlight

Since Jan. 1, 53 DEQ employees have retired.

Another 14% of the department’s employees are eligible for retirement, DEQ Deputy Secretary for Public Affairs Sharon Martin said in an email responding to questions from Coastal Review.

Within the next five years, 452 DEQ employees will be eligible for retirement.

“That is another reason we are so focused on addressing recruitment and retention issues,” Martin said in the email.

But that’s no easy task in what she describes as a highly competitive labor market “exacerbated by the inability to compete with market salaries.”

In fact, 36% of employees who have quit the department say salary was a factor in their decision to leave. More than half, 56%, of job offers were declined based on pay, according to information Martin provided.

“At DEQ’s current funding levels, many budgeted salaries are not competitive in the current job market, and engineers may be one of the clearest examples,” she said. “Among state agencies, DEQ has the second highest need for engineers behind only (Department of Transportation). However, market competition for engineers makes retention and recruitment particularly difficult.”

The average and median salary for a DEQ engineer 1 is about $15,000 less than the starting salary of a N.C. State University engineer graduate. An engineer II with more than 20 years’ experience is paid “roughly the equivalent” to a fresh-out-of-college N.C. State University engineer graduate.

Martin said DEQ is taking several steps to address staffing challenges, such as bumping up salaries for 88 employees whose pay was below the minimum under the state’s compensation system; targeting retention bonuses for engineer and environmental specialists; and evaluating a multistep, department-wide plan to narrow the public-private sector pay gap for staff who meet certain education and experience qualifications.

When real wages for state employees are not keeping up with the private sector and inflation, now at a 41-year high, that makes it incredibly difficult to retain “the kind of dedicated and talented and knowledgeable public servants that we rely upon to make modern life possible,” said Patrick McHugh, research manager at the N.C. Budget & Tax Center.

“I think for all that we’ve heard about the challenges that private sector employers are experiencing with hiring people there’s been incredibly little attention paid to a similar crisis that is playing out among public sector employees, specifically state employees,” he said.

McHugh said he first saw a disparity between the loss of state, federal and local government employees when he examined data released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

According to that data, North Carolina has lost thousands of state employees, but that’s not the case in local or federal government sectors.

Questioning whether he was looking at erroneous data, McHugh cross-referenced the bureau’s numbers with that of the N.C. Office of State Human Resources. The results were the same.

Cracks revealed

McHugh said that one of the important things to keep in mind when talking about the current decline of state employees is the pandemic.

Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic that descended on America in early 2020 unveil weaknesses in government.

Years before the pandemic, DEQ was one of the chief targets of cuts and underfunding under the administration of Gov. Pat McCrory, who was governor from 2013 to 2017.

“Even though the proportional decrease for (DEQ) employees may not be as severe as some other parts of state government, the fact that they were already barely keeping things together because of years of cuts means that those kinds of losses can be even more severe than just the pure job numbers may indicate,” McHugh said.

It’s been five years since per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, were thrust into the spotlight in North Carolina after the public was made aware that the man-made chemicals have been discharged into the Cape Fear River, the air and the ground for decades by DuPont spinoff, Chemours.

The PFAS crisis overlays other long-term issues like the impacts of climate change, further exacerbating limited staff resources.

“When those sorts of things happen, that pulls capacity away from other priorities within an institution like DEQ and when an institution like DEQ is already stretched to the limit that means that other important priorities like climate change, like other kinds of water protection, like other kinds of environmental protection, has to be sacrificed to address the new challenge that has just arisen,” McHugh said.

For DEQ staff, that means more work and longer hours.

“The result is longer lead times on some permitting processes and increased stress on our staff,” Martin said.

‘It hits us in so many different ways.’

Chris Gibson, president of the Wilmington civil engineering company TI Coastal Services Inc., noticed the squeeze on DEQ employees starting around the time Hurricane Florence hit the North Carolina coast in 2018.

The storm’s record-breaking storm surge topped 9 to 13 feet and produced catastrophic flooding in coastal and near-coastal inland counties.

“It’s progressively getting worse,” Gibson said of DEQ’s staffing shortages. “I say this and, if you’re going to quote me on anything, this is not the fault of staff. It’s the fact that there’s not enough staff for the amount of stuff that’s going on. We’ve been in a big rebuilding scenario on the coast and we’re still running with the same number of staff or less. We’ve had so much work that’s come up from them from the hurricanes. I mean, how many crosswalks has Jason Dail had to look at in the past five years?”

Dail is a field officer with DEQ’s Division of Coastal Management’s Wilmington Regional Office.

If the state asks for a 75-day extension to review a permit, it usually takes the full 75 days because “something more urgent gets into the works,” Gibson said.

“They rarely ask for an extension and then give you a permit three days later,” he said. “You can expect whatever the time they’ve asked for is the time before it’s going to get to you so it’s tough. It’s really tough. We’ve got from November 15 to the end of March or April, depending on exactly what the job is. If we’re trying to get a permit in September and all of a sudden there’s another 75 days put on it we’re thinking we’re 60 days ahead and now we’re 20 days behind. So, all of a sudden, I’m stuck with staffing needs or holes in my staffing or I’m overstaffed because things have to shift. It hits us in so many different ways.”

Dana Sargent, executive director of Cape Fear River Watch, expressed frustration about the staff shortages, saying environmental nonprofits are also overwhelmed, working with limited staffs and funding.

“I feel like there’s a lot of great people at DEQ doing great things,” she said. “I appreciate the recent work coming out of the DEQ on PFAS is strong and I’m very much grateful for that work. That being said, it’s their job. They absolutely need more money. There’s huge amounts of pollution in our state that we’re trying to protect our communities from and we’re doing all we can also on limited funding, also begging for grants and then having to prove to our grantors what we’re doing to spend our capital on that. So, it is frustrating to hear from a state agency that they just don’t have the funds while we’re scraping our funds to do this work.”

‘Stop the bleeding’

In late September, the N.C. Tax & Budget Center released a report highlighting the 2022-23 state budget’s failures to address the effects of inflation.

Though the state economy is robust, state spending relative to the economy is at an all-time low, according to the report.

Rather than use federal COVID-19 relief funding funneled to the state to address the pandemic crisis, state legislators essentially used those funds for things typically paid for by state dollars and diverted state funds to reserves.

And legislators did this without giving North Carolina residents the opportunity to voice their opinions, whether it be through committee hearings or through their elected representatives voting on the floor.

Instead, the House and Senate chambers released their conference report on the budget. Amendments cannot be made on a conference report and the report cannot be referred to a committee.

Legislators transferred $9.1 billion to more than a dozen reserve accounts in the Fiscal 2022-23 budget. Nearly $4.2 billion of those are unappropriated, including $1 billion placed in a newly created stabilization and inflation reserve.

“I think it’s important for the residents of North Carolina to know that we have billions of dollars sitting on the sidelines in a moment of ongoing crisis and that is just something that not enough conversation has been had about,” McHugh said. “Just stop the bleeding. The reality is we have the money in hand right now to give the kinds of raises that would at least insulate public servants from the effects of inflation. It will take years to rebuild the capacity in DEQ and other parts of state government that we have lost.”