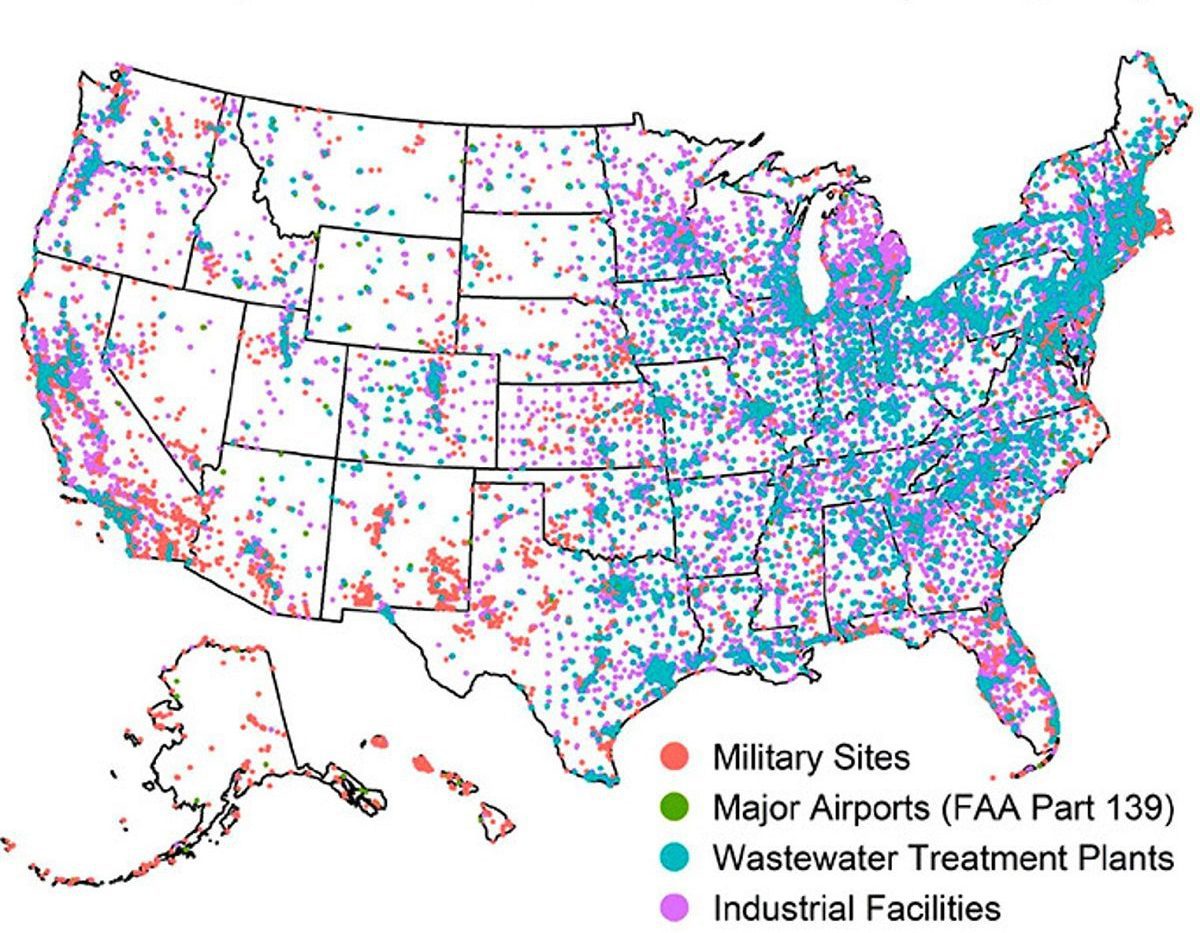

Researchers for a recent study found that 57,412 sites nationwide, including 1,452 in North Carolina, are presumed to be contaminated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

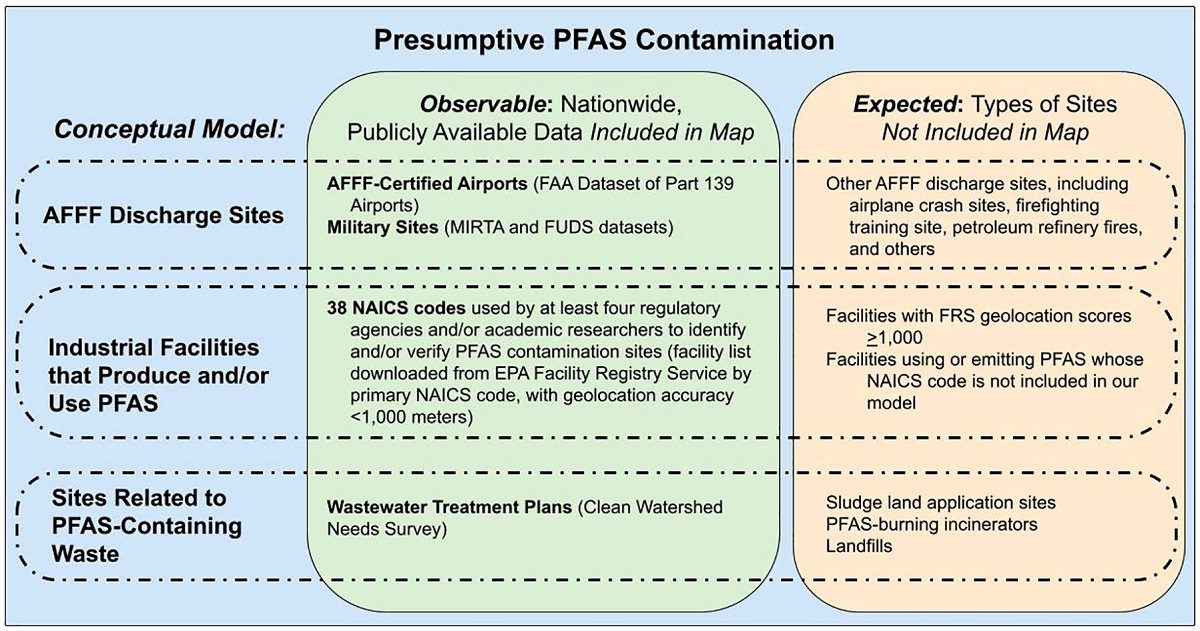

The PFAS Project Lab research team published in mid-October its findings, “Presumptive Contamination: A New Approach to PFAS Contamination Based on Likely Sources,” in Environmental Science & Technology Letters. The team concluded that PFAS contamination should be presumed at certain industrial facilities, sites related to PFAS-containing waste, and locations where fluorinated firefighting foams have been used.

Supporter Spotlight

The PFAS Project Lab, based at Northeastern University in Boston, studies social, scientific and political factors related to PFAS and researches contamination through collaboration with impacted communities, researchers and nonprofits. The lab is supported by the National Science Foundation, The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and Whitman College.

Researchers explain in the paper that because data on the scale, scope and severity of PFAS releases and the resulting contamination nationwide are uneven and incomplete, the team developed what they call the “presumptive contamination approach” to determine possible sources of contamination.

To do this, the team used previous research that identifies suspected industrial PFAS dischargers, state-based studies that use PFAS testing data to identify suspected categories of contamination, self-reported PFAS release data from industrial users, and numerous studies on specific PFAS-contaminated sites to compile the single map to find probable contamination. The map includes sites that are often sources of contamination, but where testing has not confirmed the presence of PFAS, according to the study.

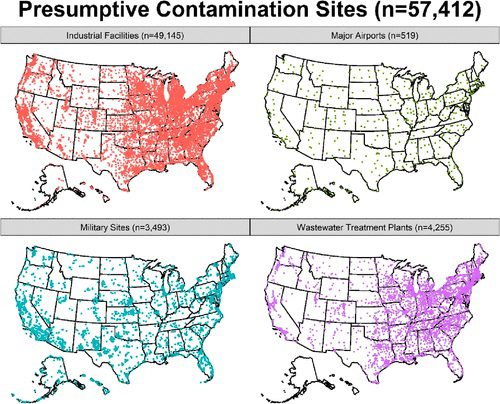

Of the 57,412 sites presumed to be contaminated with PFAS in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., 9,145 are industrial facilities, 4,255 are wastewater treatment plants, 3,493 are current or former military sites, and 519 are major airports. The report adds that proximity to contamination is consistently related to higher PFAS levels in drinking water, and consuming contaminated water is associated with higher PFAS blood levels.

“While it sounds scary that there are over 57,000 presumptive contamination sites, this is almost certainly a large underestimation,” Dr. Phil Brown, director of Northeastern University’s Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute and coauthor on the paper, said in a statement. “The scope of PFAS contamination is immense, and communities impacted by this contamination deserve swift regulatory action that stops ongoing and future uses of PFAS while cleaning up already existing contamination.”

Supporter Spotlight

PFAS exposure has been associated with increase in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, decreased antibody response to vaccines in children, decreased fertility in women, increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension and/or pre-eclampsia, kidney and testicular cancer, thyroid disease, chronic kidney disease, elevated uric acid, hyperuricemia, and gout Liver damage, immune system disruption, and adverse developmental outcomes, including small decrease in birth weight and altered mammary gland development, according to the lab.

Related: Webinar, meetings set on PFAS blood test results

Dr. Linda Birnbaum, coauthor on the paper and scientist emeritus and former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program, reiterated to Costal Review that “Contamination is everywhere — often in places we never suspected.”

She said in the release that “not only do we all have PFAS in our bodies, but we also know that PFAS affects almost every organ system. It is essential that we understand where PFAS are in our communities so that we can prevent exposures.”

Dr. Alissa Cordner, senior author on the paper and co-director of the PFAS Project Lab, said that they know PFAS testing is very sporadic, and there are many data gaps in identifying known sites of PFAS contamination.

“That’s why the ‘presumptive contamination’ model is a useful tool in the absence of existing high-quality data,” she said.

Cordner explained to Coastal Review in a follow-up interview that because most of the country does not have extensive testing data on PFAS contamination sites, the researchers’ model — presumptive contamination approach — can help decision-makers prioritize locations for future testing and regulatory action.

The research team used already-published scientific studies and government research programs that have identified specific types of locations that were sources of PFAS contamination.

“For example, extensive testing at Department of Defense sites suggests that military bases are presumptive sites of PFAS contamination because of the use of fluorinated firefighting foams,” she said.

“We also gathered information about what types of industrial facilities are likely using and emitting PFAS. We found 11 high-quality studies or regulatory processes that targeted or identified specific types of industrial facilities, and we chose to include industry categories if they were identified on at least four of these lists,” Cordner said.

“We then gathered all of the publicly available, high-quality, nationwide data we could on the different types of presumptive PFAS contamination sites, and we kept in only the data that was specific enough in terms of its geolocation data that we could use it to create a nationwide map. This left us with over 57,000 identified sites in the United States.”

The research team checked their model’s accuracy by comparing 500 known contamination sites from the PFAS Project Lab’s Contamination Site Tracker against the likely contamination sites identified with the presumptive contamination map. They found that 72% of known contamination sites were either included in the map of presumptive contamination sites or captured by the overall conceptual model, even if those sites couldn’t be mapped at the national scale, according to the report. Some suspected sources of contamination, such as airplane and railroad crash sites, hydraulic fracking sites, and sewage sludge land application sites were not included on the map because of a lack of available nationwide data.

With the development of the presumptive contamination concept, plus validating the model against known contamination sites, the paper states it “provides a rigorous advancement to previous academic and regulatory models and having a standardized methodology allows researchers, regulators, and other decision-makers at various geographic scales to identify presumptive PFAS contamination using publicly available data.”

Dr. Kimberly Garrett, post-doctoral researcher at Northeastern University and coauthor on the paper, said that because PFAS testing is expensive and resource intensive, “We have developed a standardized methodology that can help identify and prioritize locations for monitoring, regulation and remediation.”

In response to a request for comment on the study, a representative with the state Department of Health and Human Services said in an email that the department continues its work to understand the impact and effects of PFAS and other “forever chemicals” on the health of North Carolinians.

“The article provides a valuable estimate of PFAS contamination in NC that can help NCDHHS, communities, and private well users be more aware of sites where people might have more exposure to PFAS,” according to representative.

“Private well users can utilize the map and community resources from the article, in conjunction with other NCDHHS private well guidance, to help decide whether they should test their wells for PFAS or other potential contaminants. To assist with these efforts, NCDHHS has developed several documents to help residents in impacted communities understand more about PFAS, see here: PFAS Factsheet, GenX Factsheet, PFAS Testing and Filtration, and PFAS Clinician Memo.”