ELIZABETH CITY— LeVern Davis Parker’s family has deep roots in the boatbuilding history of Dare County.

The Manteo native recently released a book, “Our Family, Its History Their Boats: Six Generations of Boat Builders in Dare County,” from which she shared highlights during a presentation Oct. 5 at Museum of the Albemarle, part of the museum’s monthly “History for Lunch” series. Copies of the book are for sale in the museum gift shop.

Supporter Spotlight

Parker is a descendant of George Washington Creef Sr., who developed the shad boat that was adopted in 1987 as the state boat of North Carolina. Creef Sr. was born in East Lake and moved to Manteo around the time of the Civil War. He worked for the U.S. Navy, hauling coal.

“He crafted a boat that could maneuver shallow sound waters of Roanoke Island called a shad boat,” Parker said.

White cedar, a lightweight, native wood with a natural ability to resist rot, was used for the shad boats, which were powered by three sails. Fishermen used the boats to retrieve fish from pound nets in shallow waters and unpredictable wind shifts, according to the state Department of Cultural Resources.

“Two men were needed to operate this new design of boat. One to steer and one to shift the ballast, which often weighed 50 pounds or more,” Parker said. “They were workboats, and over the years had gone through many changes.”

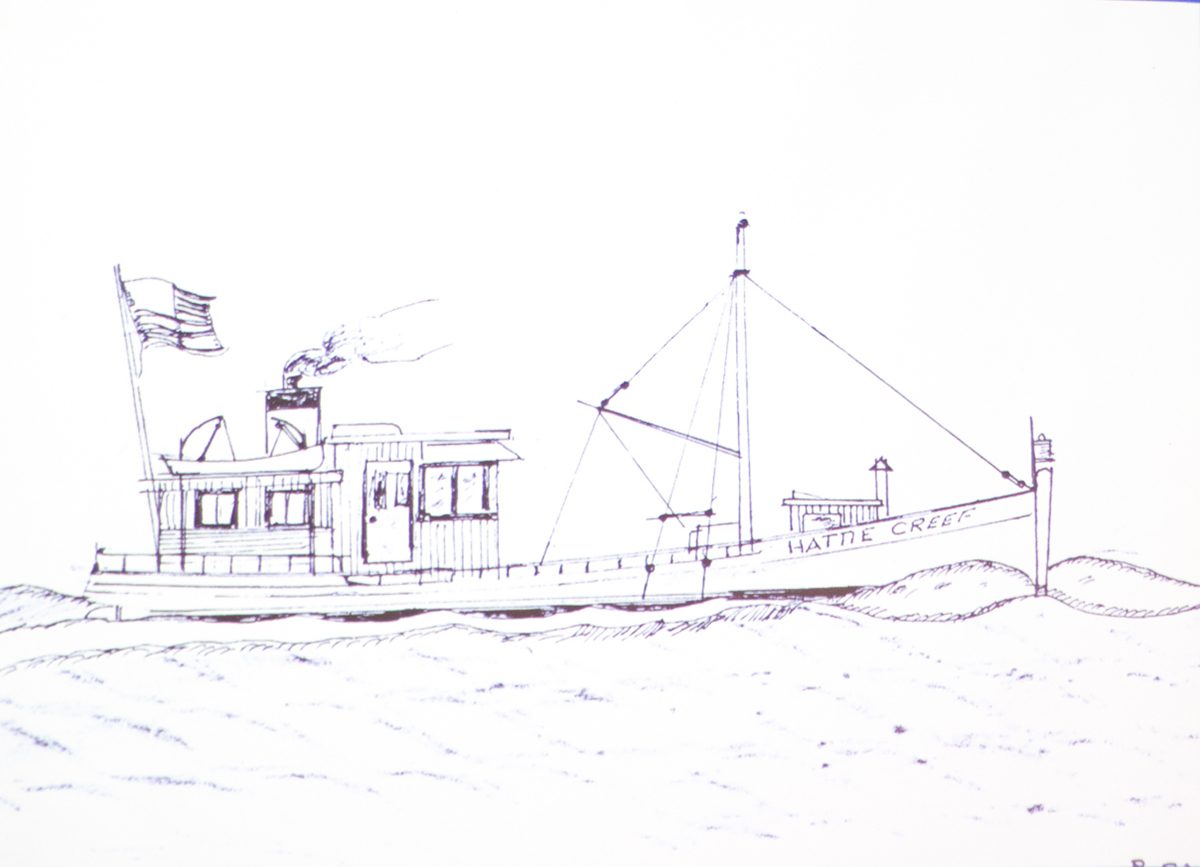

Parker’s grandfather, George Washington Creef Jr., learned the boatbuilding trade from his father. One boat he built named the Hattie Creef steadily “plied the waters of northeastern North Carolina” for 70 years, Parker noted.

Supporter Spotlight

“The book refers to both the boat and my great-aunt Hattie as Renaissance women,” she said. “They were able to change and reawaken with the times.”

The boat Hattie Creef evolved from being powered by sails to a gas engine to a diesel engine over the years and was used as a fishing boat, sailboat, oyster boat and recreational boat.

But its lasting claim to fame was making a trip from Elizabeth City to Kitty Hawk, taking “two young brothers and their crates” containing airplane parts. Orville and Wilbur Wright would, from there, launch aviation history.

Creef Boatworks was an extensive operation in Manteo and included Creef and Creef Railways, which Creef Jr., and his brother Benjamin Howard Creef jointly owned and operated, Parker said.

Her father, Vernon Davis, and her uncle Ralph “Buddy” Davis continued the family tradition of boatbuilding but took a different tack.

“They weren’t really interested in the utilitarian boats of the Creefs,” Parker said. They were instead “interested in developing boats for speed.”

In the 1930s, her uncle was called “the Speed King,” she said. Later, around the turn of the century, her father was called “the ‘Master of Going Faster’ – something he was pretty proud of in his late 80s.”

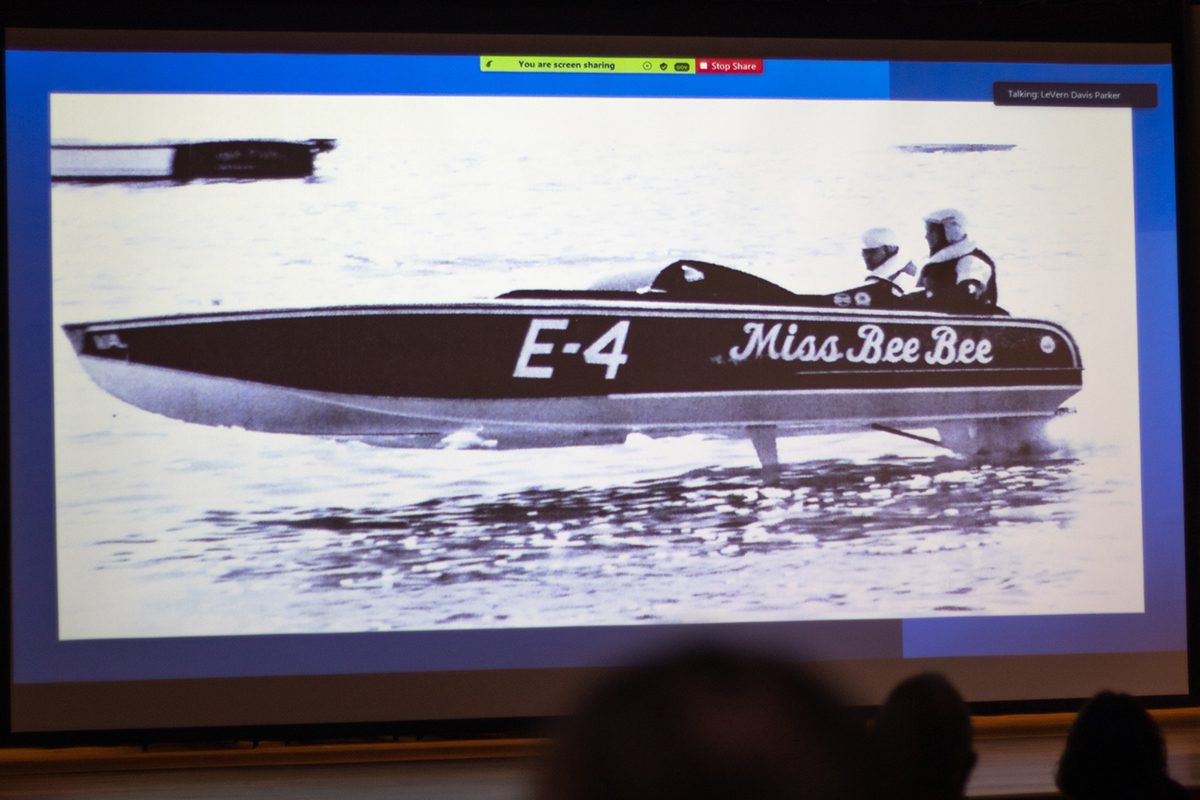

They’d started building racing boats as boys and in their late teens and early 20s “raced all over North Carolina” in boats with names such as Miss Ford, Miss Chevrolet and Dodger, Parker said. They built boats in the garage, backyard and barn and worked in their family’s store, which they viewed “as a way to get spending money for their first love: Boats.”

The brothers built many Class E runabouts, which were popular on the East Coast from the 1930s to the 1960s, and later in Louisiana and southern Florida, Parker said. The boats they built were for “the weekend racer” who would return to his job on Monday.

Boat racing stopped in the country from 1939 until 1945 because of World War II, but the brothers would later build some of the most successful race boats in their era.

“I knew growing up they had built race boats, but really until I started researching, I wasn’t aware how important those boats were on racing circuits in the 1950s and ’60s,” Parker said. “I was amazed at the number of local, national and international championships they held. Neither would boast about it — that just wasn’t their demeanor.”

During Parker’s talk about about her family’s connection to boatbuilding, she encouraged the audience to return Monday to view a new exhibit, “Rock of the Eye: Boatbuilding Traditions Around the Albemarle,” which traces the region’s extensive maritime heritage from the Indigenous canoes dating back to as early as 500 B.C. to modern boatbuilding techniques.

“Rock of the eye” means building by tradition and building right, according to Don Pendergraft, director of regional museums.

The term comes from the “Hoi Toider” brogue of Ocracoke and Engelhard, and described how area boatbuilders historically used their eye and lining a finger up with their eye to perfectly make a symmetrical boat. “It has to be symmetrical to float,” he said.

“In the exhibit, you will see techniques that would have been very familiar to my father, my uncle, my grandfather and my great-grandfather,” she told the crowd.

Parker also encouraged attendees to visit Manteo, where they can see two restored shad boats built by her family members.

After her presentation, Parker signed copies of her book at the museum gift shop.

Julie Pipkin said she attended the talk because her two sons are Creefs and distantly related to Parker.

“They love the water (and) love boats,” the Elizabeth City resident said. “I enjoyed the history and want to share it with my sons.”

Beverley and Michael Egolf recently relocated to Elizabeth City from New Jersey and said they found the presentation informative. Michael Egolf, a new Museum of the Albemarle volunteer, had worked as a diver for 10 years at New Jersey Maritime Museum.

“We’ve always been interested in boats,” Beverley Egolf said, adding that Parker “really knows her stuff.”