Second in a series.

HATTERAS — Once the quiet and well-behaved counterpart to feral Oregon Inlet, Hatteras Inlet is now repeatedly afflicted by shoaling that defeats routine maintenance of the critically important Ocracoke ferry routes.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s ever-evolving,” Catherine “Cat” Peele, planning and development manager for the state Ferry Division, said in a recent interview. She added that bathymetric surveys are done regularly to keep close tabs on sand buildup. “The channel is constantly changing. We’re at the mercy of Mother Nature.”

Nearby channels outside Hatteras Inlet, the passage from sound to sea between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, have also become bigger problems.

On Monday, June 6, for example, the Ferry Division announced that it had been forced to reduce its scheduled ferry runs to and from Swan Quarter and Cedar Island because, in addition to labor shortages, Big Foot Slough just outside Ocracoke’s Silver Lake was clogged.

Severe shoaling in that Pamlico Sound channel, according to the announcement, had created dangerous navigation issues for the large sound-class ferries, causing the vessels to be temporarily pulled from service. Emergency dredging by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is to happen as soon as possible, and ferry runs will return to the normal summer schedule when channels are cleared to a safe depth, the statement said.

Ferries are essential transportation for residents of this tiny barrier island situated at the southern end of the Outer Banks. Accessible only by boat or small airplane, the charming historic village and beautiful undeveloped beaches are magnets for thousands of tourists every year.

Supporter Spotlight

In addition to repeated shoaling issues in Big Foot Slough, just in recent months the free Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry, the busiest of the state’s seven ferry routes, has struggled to transit shoaled spots in the inlet’s ferry channel, occasionally bumping bottom. And an inlet channel used mostly by the Coast Guard and commercial and recreational fishing vessels and charter boats had, after repeated attempts to dredge, become impossible for the Corps to maintain, leading to diversion of traffic to a newly marked natural route.

“Long range,” Peele said, “it’s hard to know what that inlet will look like.”

Essential routes, difficult challenges

At the same time, the North Carolina Department of Transportation worries that an erosion hot spot long threatening the only highway on Ocracoke Island may soon suffer one too many storm breaches.

Traffic coming off the Hatteras ferry at the north end of Ocracoke Island must drive 13 miles through undeveloped Cape Hatteras National Seashore on N.C. 12 to reach the village. The most vulnerable section of roadway is about 5 miles south of the ferry terminal. If the road becomes impassable, the island’s robust tourism economy would suffer a huge blow.

That leaves NCDOT, which oversees the ferries, and the Corps having to contend with difficult coastal challenges — primarily erosion and shoaling — for transportation in Hatteras Inlet and on Ocracoke Island that are worsening with the effects of climate change.

Earlier this year, Brig. Gen. Jason Kelly, who has served since June 2020 as commander of the Corps’ South Atlantic Division, met with Dare and Hyde County and National Park Service officials at the Dare County Administrative Building in Manteo to listen to their concerns, including persistent maintenance problems in the waterways.

Although no immediate action was taken, the agency has provided additional funds for emergency dredging in the inlet and found a new approach, expanding its authority in the inlet to do projects.

In October 2020, then-U.S. Secretary of Transportation Elaine L. Chao announced the designation of the North Carolina Ferry System as a Marine Highway Project, the first in the state. Marine Highways are defined by the federal government as alternatives to traditional transportation methods. With the designation, the ferry division will be able to apply for federal funding to modernize and improve its vessels and infrastructure, according to the announcement.

The North Carolina Ferry System, the second-largest in the country behind Washington state, is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year. As part of its remembrance, the division is asking ferry passengers and staff to share ferry experiences over the decades. To contribute, visit the Ferry Tales website.

Because the ferries got their start on the Outer Banks, it’s expected that some stories will be about ferry mishaps, including being stuck on shoals — more so lately.

Authorized in 1962, the Rollinson Channel Project, which includes the Hatteras ferry channel, has always been dredged as needed, mostly by the Corps’ government dredges.

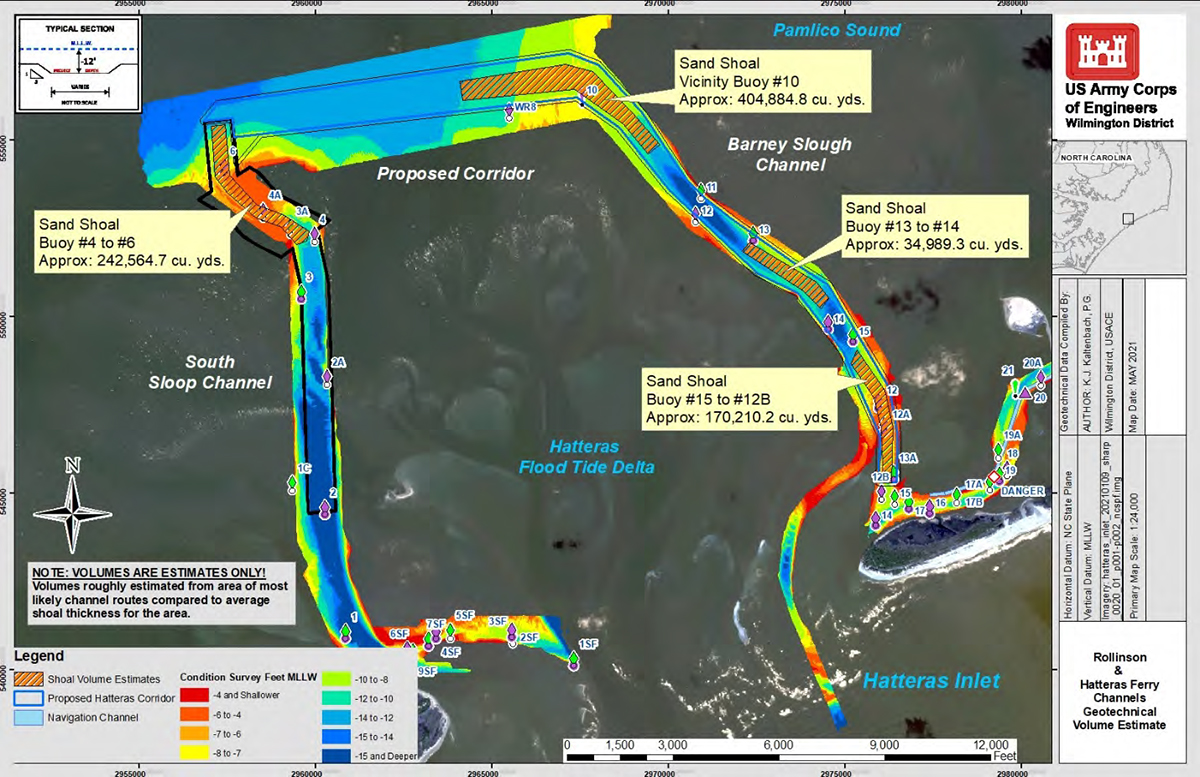

As detailed in the agency’s Hatteras Ferry Channel Realignment draft environmental assessment issued in October 2021, the ferry channel comprises a 100-foot-wide channel with an authorized depth of about 12 feet stretching from the Rollinson Channel to the inlet gorge and another channel with similar dimensions that follows the “best deep-water route” to the gorge.

All was well until the 1990s, when the spit at the end of Hatteras Island gradually started eroding, in turn widening the inlet and allowing more sand to wash into channels. After a series of hurricanes in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the situation worsened. By 2013, the ferry channel became hopelessly clogged and unnavigable, and the Hatteras-Ocracoke ferries began using a longer horseshoe-shaped natural channel.

The former 4-mile ferry trip from the Hatteras terminal to the Ocracoke “South Dock” terminal on the north side of the island doubled in length and went from about 40-minutes to about 60 minutes. While the number of round trips had to be reduced, fuel costs increased considerably. Lines and wait times at the stacking lanes at the Hatteras village terminal in Hatteras got much longer.

In recent years, Sloop Channel, just outside the South Dock Terminal started shoaling, which created additional delays.

A new passenger vessel, the Ocracoke Express, was launched three years ago to relieve some of the backup on the Ocracoke-Hatteras route and to give visitors another option. The ferry, which costs $5 each way for adults and operates in the summer only, can be reserved online ahead of time. Free trams that stop at numerous village attractions are also offered for passengers on the Ocracoke side.

But in Big Foot Slough, shoaling that dangerously narrows the channel can also be a problem for the Ocracoke Express, which comes into Ocracoke Village at the Silver Lake terminal.

An alternate channel

In interests of ensuring that the sound ferry operations are not disrupted, Peele said, there have also been discussions about obtaining dredging permits for a nearby possible alternate channel known as Nine Foot Slough.

Once the Hatteras Inlet realignment is implemented, it would provide the regulatory flexibility that will foster more efficient and responsive maintenance of the portion of the Hatteras Ferry Channel that follows deep water, according to the draft assessment, “due to the changes in shoaling patterns caused by the dynamic nature of the Hatteras Inlet system.”

Peele said that with more flexibility, the Corps should be able to plan with more certainty.

“We’re hoping that with the realignment with the Corps, they’ll be able to dedicate their equipment,” she said.

No doubt, it will be a much-needed improvement in addressing the constantly migrating shoals, but it does nothing for Big Foot Slough, nor would it alleviate the threat to N.C. 12 or any other trouble spots that may materialize outside the designated area.

An August 2020 Ferry Division overview provided by Deputy Director Jed Dixon reported that funding to dredge Big Foot Slough, a federal channel, has decreased and is inconsistent year to year

Impacts to the dangerous shoaling in Big Foot Slough, which is also spelled Bigfoot Slough, the report said, include “vessels hitting bottom, damage requiring emergency repairs, departure cancellations, schedule modified to use only certain smaller vessels.”

In 2020, the Ferry Division workforce totaled 61, according to the report, compared to 100 in 1998. To varying degrees, difficult positions to fill include marine engineers, painters, mechanics, welders and sandblasters.

With inadequate staffing and work space, Ferry Division maintenance and refurbishment projects were delayed, the report said, and emergency repairs reduced personnel and space needed for planned projects.

The situation two years later serves as an example of that squeeze on resources. In May 2020, the division announced that three ferries running the Pamlico Sound routes and one on the Hatteras route could not operate for a brief time because of mechanical issues.

To address ongoing erosion at South Dock, the division has installed sheet pile to stabilize the point as a short-term measure, although state law on hardened structures limited its effective length. But the National Park Service, which owns the land where the Hatteras and Ocracoke ferry terminals are, and NCDOT have agreed that stabilizing the ferry terminals and the Ocracoke hot spot on N.C. 12 will not last long.

Terminal relocation

A proposal to relocate South Dock closer to the Ocracoke Pony Pens on the west side of the island is still being considered by NCDOT and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Although the new location would bypass the eroding ferry basin and the problematic hot spot on N.C. 12, it would present numerous complications, including potential negative effects on submerged aquatic vegetation, and increased time and staffing requirements for ferries to travel to the new terminal.

An amended feasibility study first completed by NCDOT in 2016 of long-term solutions to erosion on the island’s north end proposed building the new terminal near the middle of the island. Depending on the ferry used, that location would add about 15 to 45 minutes to the current one-hour trip between Hatteras and Ocracoke, the document said. The number of trips would have to be reduced, unless additional staff and ferries were provided.

If the terminal were to be moved, NCDOT would no longer maintain the portion of N.C. 12 beyond the new location. Further, National Seashore Superintendent Dave Hallac has said that, with a road no longer bisecting the land, the Park Service would likely close off the north end of the island as a pony preserve or for other natural uses.

But that’s not an idea favored by island residents, who don’t want to lose access to nearly half their island, said Randal Mathews, an Ocracoke resident and Hyde County commissioner.

But it’s not a new idea; nor is the eroded hot spot a new problem.

During a 1999 meeting with the Outer Banks Task Force, N.C. State University civil engineer John Fisher, then-chair of the task force science panel, called a dune at the hot spot that was reconstructed after Hurricane Dennis a temporary “Band-Aid.”

“We seriously think you should think about abandoning that whole stretch of road and relocating the ferry system,” he told the task force, according to a Nov. 7, 1999, article in The Virginian-Pilot.

In a January 2004 Pilot article, then-National Seashore superintendent Larry Belli had told the task force during its October 2003 meeting that beach nourishment would be a last resort.

“I think we really need to look seriously at the alternative of moving the ferry terminal while we can do it,” Belli told the panel. “I would just go up as far as I can on the island. There would be some pluses and minuses, but there is with anything.”

And 19 years later, NCDOT is still wrestling with what to do about the same hot spot.

“I’d say on N.C. 12, this is probably the top priority, if not very close to the top priority,” Paul Williams, NCDOT North Carolina Division 1 environmental officer, said during an April 28, 2021, virtual meeting of the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission.

Between 2010 to 2021, according to department records, costs for N.C. 12 storm-recovery work on Ocracoke Island totaled $15,142,646.

For now, NCDOT will continue to patch the road together the best it can while it weighs solutions.

Peele said a grant application, if approved, would allow continued analysis of the feasibility study to determine what needs to change to operate the ferry under the federal Marine Highway designation.

The feasibility study would likely last for about a year, she said.

If an actual move was decided on, the project would have to be added to the state’s transportation improvement plan, she said, and it’s not clear whether it would meet the funding protocol.