Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

Tyrrell County in North Carolina’s Albemarle region was formed in the earliest years of Colonial settlement, but Tyrrell does not have the historical reputation of other early counties.

Supporter Spotlight

It has the smallest population in North Carolina and is known more for its animals and creeks than its historic sites. Despite its reputation as a large swamp mostly devoid of people, Tyrrell has a fascinating history that has kept settlers and visitors coming for the past three centuries.

Following the establishment of Albemarle County in the 1660s, settlers began to move west and south in search of fresh lands for corn and tobacco production. Many of these settlers ended up on the southern side of the Albemarle Sound. At first, these areas were part of the original North Carolina counties: Chowan, Pasquotank, Perquimans, and Currituck. But in the 1720s, the population grew to a point where settlers required representation in a more accessible court.

These men and women were granted a new county in 1729, one that extended from the Roanoke River to the Atlantic Ocean north of Bath County, according to “The formation of the North Carolina counties, 1663-1943” by David Leroy Corbitt. The county was named after Sir John Tyrrell, a lord proprietor who had died that year. Over the next 150 years, Tyrrell County’s territory was reduced substantially. Its western third became Washington County in 1799, while the eastern third became Dare County in 1870.

Tyrrell County was one of the poorest and most sparsely populated in all of North Carolina. The vast majority of the county was swampland. Swamps had to be drained with ditches and canals to produce any sizable farmland.

A few planters tried their hand at this arduous project. Most notable among them were Ebenezer and Charles Pettigrew, who tried to develop the area between Lake Phelps and the Alligator River with some success. These efforts led to a limited network of plantations that grew primarily corn and wheat. Prominent residents helped establish Columbia, which is the lone incorporated town in Tyrrell County and situated on the Scuppernong River in the northern section of the county.

Supporter Spotlight

The Scuppernong River also became famous at this time for its connections to the scuppernong grape. Scuppernong grapes are a bronze variety of the more widespread muscadine grape. This grape grows throughout North Carolina, but it was first written about in connection to the river in the early 19th century. Since that time, scuppernongs have become a well-known variety of grape and have been used in juices and wines. The scuppernong grape was named the state fruit of North Carolina in 2001.

The work of draining and eventually tending the fields of Tyrrell County was done mostly by enslaved African Americans. They made up a third of the population in 1860, according to the Hergesheimer Map. A considerable number of free African Americans also lived in the county’s swamps. These forbidding areas, unsuitable for agriculture and lightly populated, sustained colonies of runaway slaves and other African Americans, similar to the larger groups living in the Great Dismal Swamp.

The Civil War mostly overlooked Tyrrell County. Its main contribution was J. Johnston Pettigrew, a respected Confederate brigadier general and member of Tyrrell’s Pettigrew family. Pettigrew participated in the Peninsula campaign and was a leader of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. He died from wounds sustained after Gettysburg, his loss acknowledged by Robert E. Lee as a severe blow to the Confederate Army. There is today a building on the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill campus named after Pettigrew.

Following the Civil War, development in the county remained slow. Tyrrell’s population decreased between 1860 and 1920.

A notable project during that era was the construction of the current county courthouse in Columbia. This courthouse, completed in 1903, is in the Romanesque Revival style and made of brick with arched windows and gabled dormers, according to its National Register of Historic Places nomination.

According to Alan D. Watson, writer of “Tyrrell County — A Brief History,” the county was worried about the potential of fire and banned most events from the courthouse, including “entertainment, ice cream supper, or anything of the kind.”

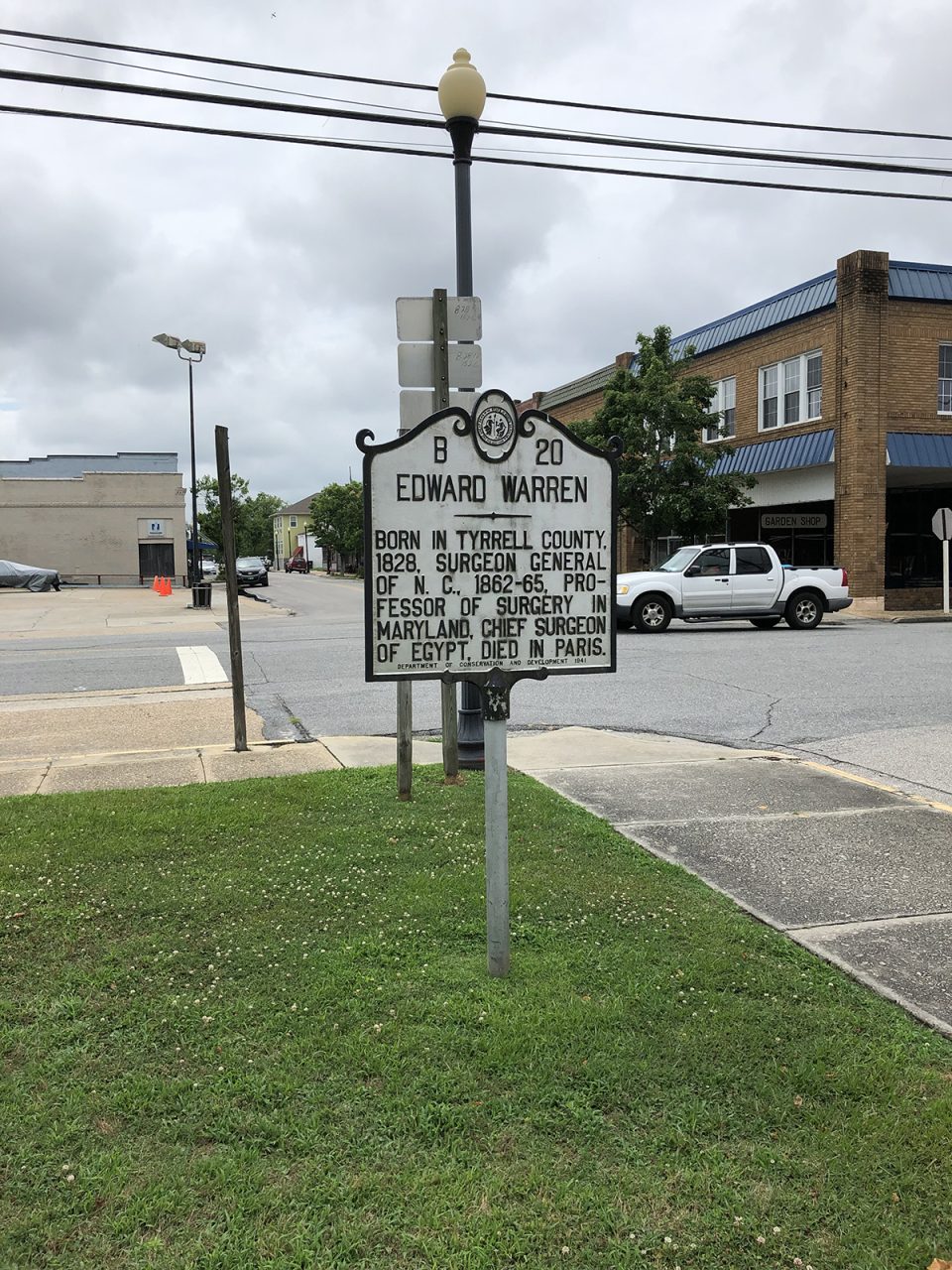

One of Tyrrell’s most famous residents, Edward Warren, did much of his work during this period. Born in Tyrrell in 1828 and afterward raised in Edenton, Warren became a celebrated doctor and medical leader in North Carolina, eventually becoming the state surgeon general. He left after the Civil War and went to Egypt, where he served for several years as an Egyptian governor’s personal doctor. Warren then spent the rest of his life practicing medicine in France, where he died in 1893.

In his memoir, “A Doctor’s Life in Three Continents,” Warren recalls how he gained the knowledge of his life in “the swamps of Carolina, the battle-fields of Virginia, the sands of Egypt, and the quartiers of Paris.”

In the mid-20th century, Tyrrell County began to benefit from its natural beauty and its proximity to other attractions. U.S. Highway 64, which connected the Triangle to the Outer Banks, came through Tyrrell in the 1920s and 1930s. This highway brought thousands of visitors each year through the county and eventually through the town of Columbia. The route, along with N.C. Highway 94 connecting Tyrrell to Hyde County, served as Tyrrell’s “windows to the outside world” according to Watson.

Tyrrell mostly failed in its attempts to become a center for industry. It was too rural and remote from other population centers. In addition, the attempts at industry that did occur, along with large-scale agriculture, polluted the pristine natural areas throughout the county.

Residents fought back, and as a result, the county eventually became the site of new state parks and wildlife refuges. Pettigrew State Park, founded in 1939, and Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, founded in 1990, began attracting visitors with miles of hiking trails, accessible rivers, and hunting opportunities.

Today, Tyrrell is mostly known for its natural beauty and its sparse population. Columbia offers a few amenities, such as restaurants and a sizable antique store, but most of Tyrrell County is dedicated to outdoor exploration and wildlife. There are nearly as many bears in the county as there are people. Visitors can explore miles of hiking and kayaking trails and engage in a wide variety of outdoor activities. Its natural wonders have defined settlement in Tyrrell County for centuries and will likely remain the basis of its economy for years to come.