As summer approaches, many North Carolinians are making plans to spend quality time at their favorite beaches, as well as the many lakes, rivers and streams across the state.

Beachgoers, in particular, whether it’s a vacation, weekend getaway or a day trip, can expect to find shorelines populated with standard-issue gear such as beach chairs and umbrellas, bocce ball sets and coolers, to name a few items.

Supporter Spotlight

Oh, and without a doubt, there will be plastic items, too. And while many people will pack out their trash, others may be less conscientious. So, who takes responsibility for the trash left behind?

The task of keeping discarded plastic from polluting the state’s waterways, and eventually ending up in the ocean, is largely the responsibility of Waterkeepers Carolina, “a science-based, environmental advocacy group,” which includes 15 organizations that are spread across the state.

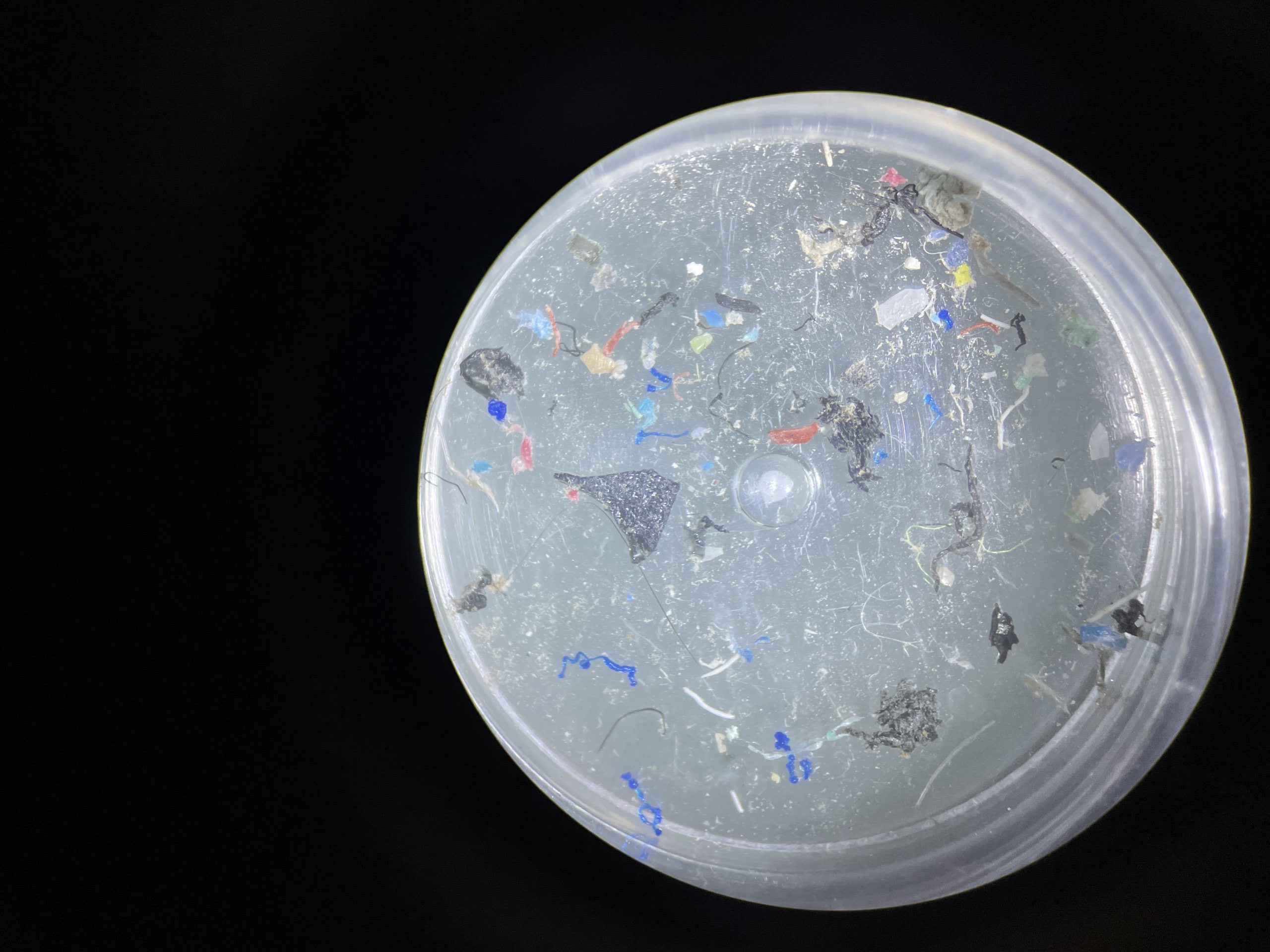

Waterkeepers Carolina is locked in a downstream battle to capture and remove a constant flow of plastic waste before it enters the ocean, where it degrades and breaks down into smaller compounds known as microplastics, which are fragments less than 5 millimeters in length, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. Microplastics are ingested by marine life and have been found in food and humans.

Even though there’s increased scrutiny of microplastics and the role they play in human and animal health, the waterkeepers are worried about the future. As more Americans buy electric automobiles, petroleum producers will look elsewhere to protect their profits. That will mean more pressure to manufacture more petroleum-based plastics, not less, resulting in more plastics polluting waterways of all sizes.

Unless something changes.

Supporter Spotlight

Downstream battlefront

Waterkeepers Carolina is a member of the parent organization Waterkeeper Alliance, a nonprofit organization that consists of more than 300 waterkeeper groups worldwide, whose “goal is drinkable, fishable, swimmable water everywhere,” according to its website. The alliance says that it “patrols and protects more than 2.5 million square miles of rivers, lakes and coastal waterways on six continents.”

Recently, Waterkeepers Carolina member Cape Fear River Watch, whose mission “is to protect and improve the water quality of the Cape Fear River Basin for all people through education, advocacy and action,” gave a seminar focused on all that plastic waste. Audrey Dunn, outreach and engagement manager, and Rob Clark, water quality program manager, spoke to a small group of attendees and online viewers.

They reported recent estimates suggesting there are between 75 to 200 million tons of plastic in the ocean already. Moreover, the amount of plastic waste entering the world’s waterways could increase from the 2016 average of 9 to 14 million tons per year to an estimated 23 to 37 million tons by 2040, according to a report produced by the UN Environment Programme.

Plastics are only one endpoint in the environmental impacts of petroleum, from fracking to extract hydrocarbons used to make plastics to air pollution and emissions from internal combustion engines to the problems associated with microplastics.

Some estimates placed the current amount of oil used in manufacturing plastic at somewhere between 8 to 10 percent of the world supply. That’s going to change.

“By 2050, it’s estimated that 20 percent of our world’s oil will be used for plastic (productions),” Dunn said.

Dunn also pointed out how low-income people of color are acutely impacted by the life cycle of plastics as manufacturing operations and landfills are often located in or near their communities.

Recycling: A broken system

In 2018, the U.S. generated 292.4 million tons of municipal solid waste, according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency. Plastic materials made up 12.2 percent of the total waste that year, some 35.6 million tons.

In that same year, some 69.1 million tons of solid waste were recycled, and, of that amount, plastic waste accounted for less than 4.5 percent of the total, only about 3.1 million tons.

One point Clark made about recycling is that a large percentage of the plastic that Americans do recycle leaves the country.

“What’s happening is, a lot of our plastic waste is being loaded onto barges and being shipped overseas. And as soon as that plastic gets on that barge, it’s considered recycled,” said Clark.

A 2019 investigative report by the Guardian found that in the previous year, “the equivalent of 68,000 shipping containers of American plastic recycling were exported from the U.S. to developing countries” such as “Bangladesh, Laos, Ethiopia and Senegal, offering cheap labor and limited environmental regulation.”

Many environmentalists and experts who study this issue argue that plastic manufacturers are flooding the market with nonrecyclable virgin plastic because it is more profitable than going to the trouble to process old plastic into recycled goods. They also argue that recycling is limited because there is not enough profit to motivate companies to invest in the infrastructure needed to increase recycling capacity. Meanwhile the industry, they say, places the responsibility of addressing plastic pollution solely on the backs of consumers.

Polyethylene Terephthalate, or PET, is the most widely recyclable plastic. PET is used in the manufacturing of plastic bottles, for instance, and is identified by the number 1 nestled inside the “reduce, reuse, recycle” symbol of chasing arrows located at the bottom of the bottle.

PET is described by PETRA, the PET Resin Association, as being “the world’s packaging choice for many foods and beverages because it is hygienic, strong, lightweight, shatterproof, and retains freshness.”

However, not everyone offers a glowing endorsement of PET plastics.

Bonnie Monteleone, founder of the Plastic Ocean Project, a Wilmington-based organization whose mission, in part, is to “incubate solutions to address the global plastic pollution problem,” said that despite its appeal as a recyclable plastic, PET can still be harmful to the environment.

“Even in our attempt to recycle PET, we’re still finding it in the watersheds, and it’s very possible that a high percentage of that is from recycled content,” Monteleone said.

Monteleone believes that the PET particles could come from some type of fabric material created as part of the downcycling process, such as a carpet. The breakdown of plastic debris into tiny compounds, commonly referred to as microplastics, have been found in water bodies, marine life, food and humans.

Macro + micro

While the growing sentiment is “we cannot recycle our way out of this plastic waste crisis,” there are tools that river watch organizations are employing to “intercept” debris from area waterways.

Neuse Riverkeeper Samantha Krop describes a device she and other riverkeepers are using in this effort.

“We’re installing these things called trash trouts, sometimes called trash bandits,” she said. “Basically, they’re … common sense, appropriate technologies that create a pervious trap that floats on top of the water and collects in the trap all of the floating macro plastic debris, and then we clean it out regularly.”

Later this year, Krop will have data to share regarding the types of waste and weight total for the debris the trash trouts collect in the Neuse River Basin.

Cape Fear River Watch also uses trash trouts to mitigate waste in the local waterways. But this year, they are adding a LittaTrap to their toolkit. According to Clark, Cape Fear River Watch is the first organization in the state to use the device, which was funded in part by a grant from the Jandy Ammons Foundation.

“You can put a trash trout in a creek that intercepts 500 stormwater drains, and you’d be collecting all that (macro-sized) litter from the drains,” Clark said about the benefits of using both devices. However, litter traps are much smaller devices that are deployed at curbside drains where they capture microparticles that would pass through trash trouts, said Clark.

‘Everything ends up in the stream’

Advocates stress that combating plastic waste is a complex problem that needs to be addressed on many fronts, including policy. They argue that the public must have a better understanding of the recycling system as well as the environmental and health impacts — at the local and global scale — of improperly managed plastic waste.

“You get somebody out into an urban waterway or creek or wetland, and they’re out there picking up trash, and seeing all the plastics that are there … that’s the best education you give somebody — that hands on experience,” Clark said.

Monteleone draws on the experience she gained traveling the world as a graduate student to study the plastic crisis to teach courses and offer young people hands-on experience in her lab.

“We can get young people out in the fields collecting samples, and we can get young people in the lab learning (with instrumentation) how to determine if (debris) is plastic or not.”

Krop agrees that education is an important tool in her efforts as a riverkeeper to “keep garbage out of the waterways.”

“Getting the world on board with this idea that we can’t throw things out the window, everything is downstream, everything ends up in the stream.”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. North Carolina Health News is an independent, nonpartisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org.