The hunt was on for all kinds of birds on Ocracoke as dozens of avid birders fanned out on the island in late December for the annual Christmas Bird Count.

A red-breasted nuthatch was what Jeffrey Beane, Stephanie Horton and Lloyd Lewis were trying to find early in the morning as they strolled the village.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s usually found in Hammock Hills,” said Beane, who is the collections manager for herpetology with North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh.

While Beane is a renowned expert in reptiles and amphibians, he also knows his birds, and a novice tagging along with him would learn a lot.

The call of a nuthatch emanating from Horton’s mobile phone brought an answering call from the live bird flitting among the shrubbery.

“Some would say that’s cheating,” Beane said about using recorded bird calls.

By 8 a.m. the three village birders had counted 30 species.

Supporter Spotlight

During the count, participants must identify the birds they see and also count the numbers of each species. Sometimes number counts can be easy for sparsely populated species such as the peregrine falcon or eastern phoebe, which will total fewer than 10 individuals for the entire count day.

But counting others can be quite challenging, especially for birds like the spunky yellow-rumped warbler much in abundance on the island from fall into early spring.

“We count the best we can,” Beane continued, noting that they count this species by the tens, “but it’s really just estimates.”

It’s even trickier with the thousands of double-crested cormorants that winter around Ocracoke.

“We count them by the 100,” Beane said, meaning they count one hundred in a long line and repeat over and over as they fly by. The highest report of this species was in 1990 when they counted about 120,000 cormorants, the highest number reported in the country.

“The bird people questioned that, but they hadn’t been down here,” Beane said. “They don’t know how many cormorants are here.”

This year, nearly 40,000 were reported.

Horton noted that not only do they count the birds they see, but they also count the species by their unique calls, chip notes and songs, known as birding by ear.

Beane, Horton and Lewis have participated in the Ocracoke count for many years with this being the 24th consecutive year for Lewis, who lives in Maryland.

“There wasn’t anyone doing the count on Ocracoke (before Vankevich and Bob Russell) started it),” Lewis said. “We stayed for the fellowship.”

On Dec. 31, when the Ocracoke count took place, the day began overcast and misty and later a thick fog rolled in.

Around the island community cemetery, Beane and Horton were hoping to spot a hermit thrush.

A brown thrasher was tallied in the meantime and Beane said that while these birds are pretty common elsewhere — it’s the state bird of Georgia — they’re not common on Ocracoke.

Fun fact: Many state birds are robins or bluebirds, Beane said. “Because they let school kids choose the birds and those are all they know.”

As one walks the village with Beane, Horton and Lewis, the three correct some misconceptions.

“Don’t call them ‘sea gulls,’” Lewis said about the ubiquitous water birds that are also seen thousands of miles inland.

“That was never a name for them,” Beane added. “They are just gulls.”

Same with that green, stringy stuff on the beach.

“It’s not ‘seaweed,” Lewis said. “It’s sea grass.”

Horton, who has been a birder for more than 30 years, reiterated what other birders say about the activity, “It’s fun to get out here and see what (the birds) are doing. Birding is a good way to get people thinking about conservation and nature.”

And that is the primary reason for the nationwide Christmas Bird Count.

Begun in 1900, it is the world’s longest-running citizen science wildlife census. It began in opposition to a tradition popular in the 19th century called Christmas “side hunts,” where people competed to see how many birds they could kill, regardless of whether they could be used for food.

American ornithologist Frank Chapman, founder of Bird-Lore, which became Audubon magazine, proposed counting birds on Christmas instead of killing them.

That year, 27 observers took part in the first count in 25 places in the United States and Canada, and this event, administered by the National Audubon Society, has grown substantially ever since.

Last year the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a lot of cancellations of counts out of safety concerns. The Ocracoke and Portsmouth counts ran with fewer than normal observers and safety measures implemented that included no new participants and a cancellation of the social “tally rally” get-together, as was the case again this year. Only 64 species were reported for Ocracoke and 57 for Portsmouth, both far lower than the average.

Nevertheless, despite the cancellations last year, 1,842 counts took place in the United States, 451 in Canada and 166 throughout Latin America, the Caribbean and the Pacific Islands.

These counts are conducted between Dec. 14 to Jan. 5 and each count site is a 15-mile-wide circle.

Ocracoke’s count, started in 1981, is on one of the last two days of the year and alternates with the neighboring Portsmouth Island count, which began in 1988. Since its beginnings, 187 species have been counted on Ocracoke and 160 for Portsmouth.

Considered by some as the “Super Bowl of birding,” these offer an opportunity to be part of citizen science and help scientists understand trends in bird populations.

Horton, Beane and Lewis covered Ocracoke’s village area while other teams spread out from Ocracoke Inlet to Hatteras Inlet counting birds on the waters, the beaches, dunes, marshes and woods.

Ryan O’Neal, a duck hunting guide, reported pintail, bufflehead and redhead ducks on the Pamlico Sound.

A few residents participated and sent yard and neighborhood reports, including seven ruby-throated hummingbirds, a record for this count.

Perhaps in part to an increase in hummingbird feeders and/or more wintering insects because of climate change, some hummingbirds that normally winter in South Florida and Central America are spending the colder months on the Outer Banks, especially in the Buxton Woods area.

In the early morning, Janeen Vanhooke and Karen Rhodes, assigned to cover South Point Road, were delayed just beyond the road’s entrance as an American bittern nonchalantly hunted for worms that had appeared on the road from an early morning rain. The bittern was one of four that would be seen throughout the day and into dusk.

Matt Janson and Peter Vankevich entered the beach from South Point Road, or Ramp 72, and were greeted not only with thousands of double-crested cormorants flying by, but also an amazing number of northern gannets mostly flying south over the water close to the beach. Others were foraging, diving spectacularly into the water for fish. This flight lasted several hours, and later in the day many continued to be seen feeding offshore.

They were joined by Amy Thompson, Ocracoke’s biological science technician for the National Park Service. At the large salt flat at the South Point, she tallied 1,159 dunlin, a small shorebird with a drooping bill. This was the most she has counted in that area, but Thompson noted the absence of several shorebird species that could be seen this time of year.

The morning got better as along the intertidal zone a large number of red knots, 205, were feeding. In the middle of the island and especially the north end, many more knots were seen, for a count total of 516.

By mid-morning, when the fog rolled in, it was enough to temporarily suspend the Hatteras Inlet ferry service. The fog limited ocean views, obscuring possible flocks of black scoters and other sea ducks. Other than that, it was much of an impediment and its eerie aesthetics cast a memorable shroud over the island.

For Rhodes, her incentive to participate derives from her art.

“My joy of drawing and photographing birds has turned into a passion to actually learn about the species and their habits here on the island,” she said.

After finishing her assignment, she headed home to count the birds in her neighborhood and her favorite heron spot.

Islander Susse Wright has participated in the count every year since the 1980s. If not too windy, she kayaks along the sound side of the island. Conditions were favorable until the fog appeared. Among the birds she found were two American Oystercatchers and a flock of about 100 Red-winged Blackbirds.

Andy Hawkins of Yorktown, Virginia, shares an equal love of surf fishing and birding and is a seasonal volunteer at the National Park Service campground. He spent much of the day on the dunes and trudging through the grasses and cedars, finding a high number of Savannah sparrows.

“The Christmas Bird Count importance cannot be overstated,” he said. “As sea coasts are affected by global climate change, one year’s data tells little, but over many years trends can show. A good day of birding, for an important cause, on a very special island.”

Some of the other count highlights: At Springer’s Point, Matt Janson had 10 snow geese fly overhead and a Baltimore oriole. He also saw a banded Ipswich sparrow and a red knot with a green satellite tag.

Lee Kimball and Tucker Scully, part-time islanders who have been doing this count for more than 20 years, reported a pair of wood ducks in Island Creek, the slough across from the campground.

Throughout the day, endless lines of double-crested cormorants streamed by. The estimate of about 40,000 was no doubt far fewer than the actual number of this species who have been present in large numbers since October.

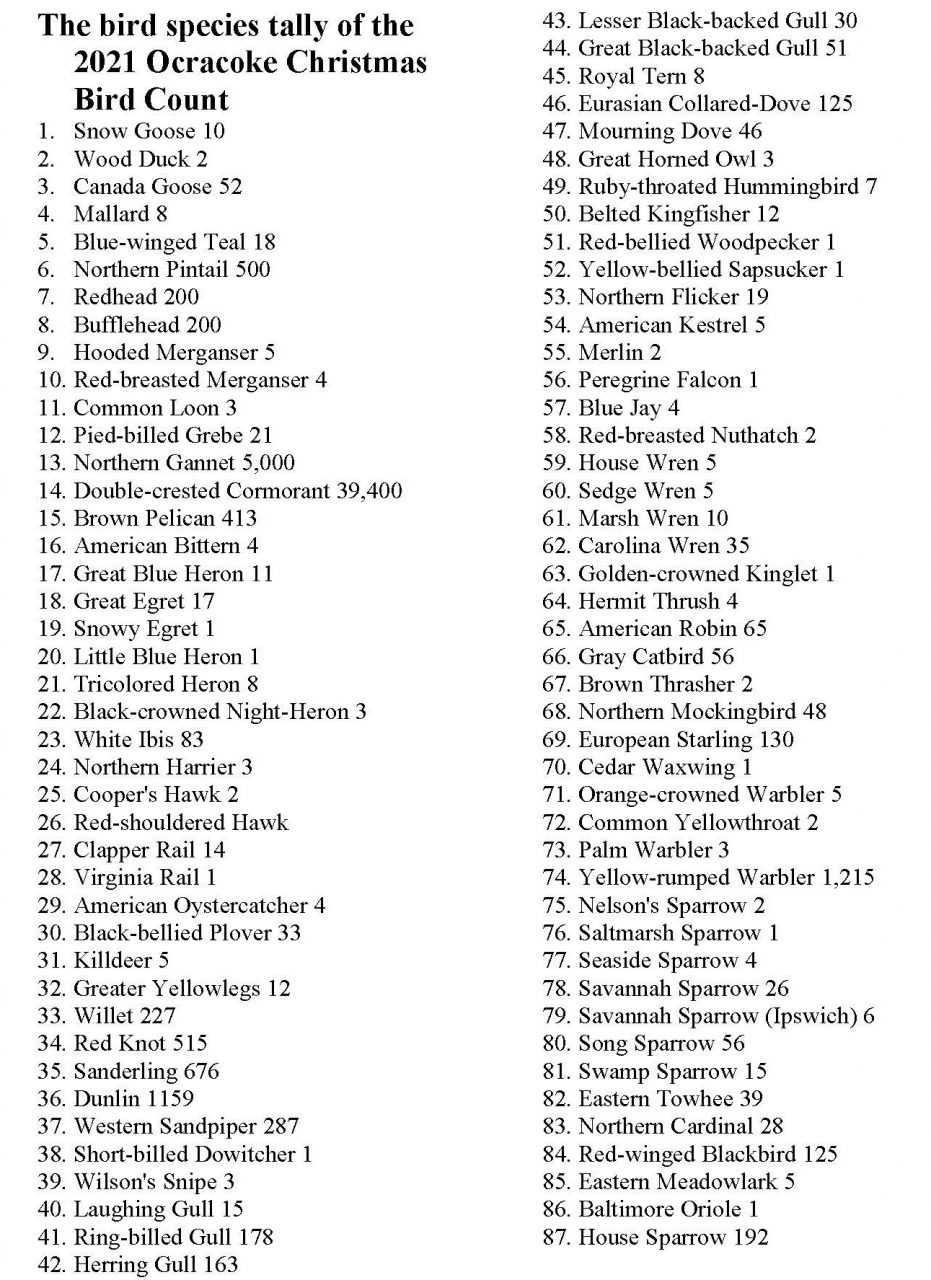

In the end, a total of 87 species were recorded on Dec. 31. A provision of the count includes birds not seen on the official day but seen on any three days on either side of count day. This is called “count week,” and four species were count-week birds including a bald eagle that has been seen regularly on the island since early fall.