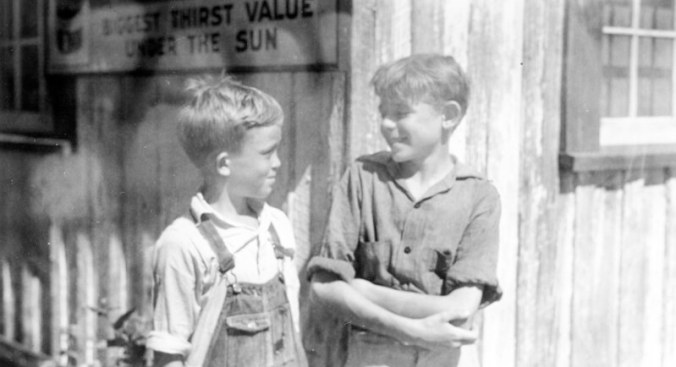

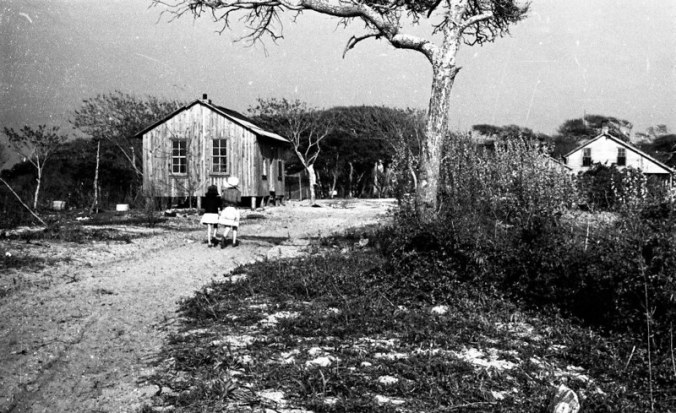

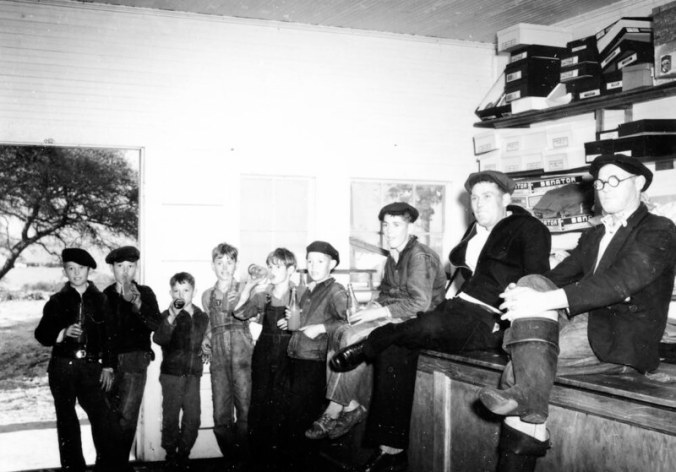

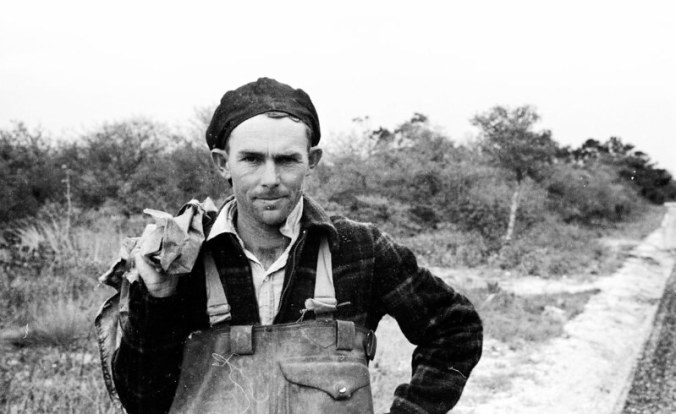

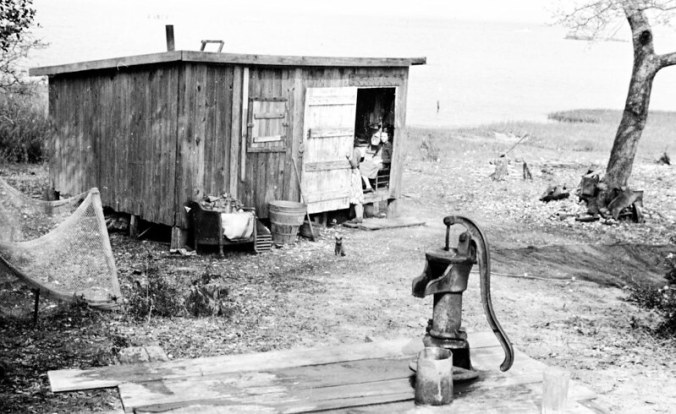

I found this group of photographs at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh. They were taken in Salter Path, a fishing village on the North Carolina coast, probably in 1938 or 1939.

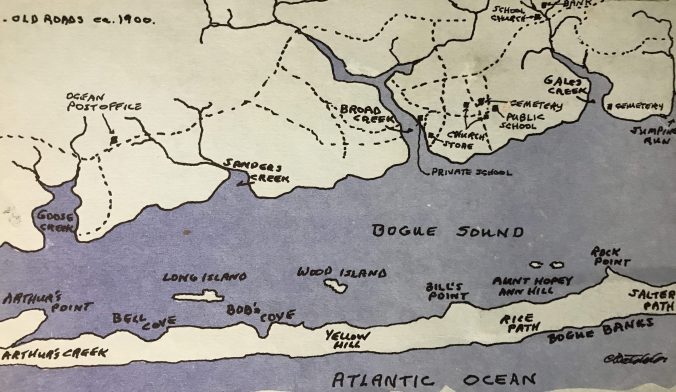

Salter Path is located on Bogue Banks, a 21-mile-long barrier island best known for being the site of Fort Macon State Park, the North Carolina Aquarium and some of the state’s most popular beach resort communities, including Atlantic Beach, Pine Knoll Shores and Emerald Isle.

Supporter Spotlight

I want to look at the history of Salter Path before the first hotels and condominiums were built there. When Charles A. Farrell took these photographs, Salter Path was the only settlement of any kind on the western two-thirds of the island.

At that time, no paved road yet led to Salter Path. People came and went largely in boats. Lights were few and far between. On a clear night, you felt as if you could see every star in the heavens.

Farrell’s photographs give us a glimpse of Salter Path just before the hotels and beach resorts showed up, the first paved road was built and all the rest.

I have paired Farrell’s photographs today with brief excerpts from a book called “Judgment Land: The Story of Salter Path,” which was written by an island visitor and sometimes resident named Kay Holt Roberts Stephens back in 1984.

Long out of print, Kay Stephens’ book lets us hear the voices of some of village’s oldest residents at that time. Several of those island people recalled when Salter Path was first settled in the 1890s.

Supporter Spotlight

The oldest of those islanders even remembered other settlements that were located on the western half of Bogue Banks in the late 1800s — Yellow Hill, Rice Path, Bell’s Cove and others. Those communities faded away in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Some of their people moved to Broad Creek and other communities on the mainland, but others helped to build the new village of Salter Path.

With the help of those people’s memories and Farrell’s photographs, we can learn at least a bit about what Salter Path and the whole western part of Bogue Banks was like in those long-ago days.

* * *

Approximately a mile west of where Salter Path is now, in a section of the island that was nestled down among live oak glades and sand dunes, there used to be a little village called Rice Path.

In “Judgment Land,” Kay Stephens described how Rice Path got its name:

“Sometime between 1865 and 1880, a ship loaded with rice wrecked on the beach. The families living on the banks … went aboard ship, filled their bags with rice and carried it across the sand dunes through the low growing shrubs, through the closely knit live oak trees and then on to the shores of Bogue Sound. There they loaded the rice on their skiffs and took it home. From then on the path and the settlement that grew up in the vicinity was referred to as Rice Path.”

According to the old islanders who visited with Kay Stephens, the move of the people in Rice Path and the other little settlements on the western part of Bogue Banks to Salter Path was prompted partly by a changing economy and partly by a changing landscape.

“By 1896, some of the settlers on the western end of Bogue Banks were becoming dissatisfied with their homesites. Each year it became more difficult to raise a garden due to the encroaching sand and … salt spray. The families living … between Hopey Ann Hill and Yellow Hill were especially affected as portions of the banks were eroding rapidly. Also, the settlers felt a need to be closer to Beaufort and Morehead City, the towns they turned to for trade. Therefore in March of 1896 the first permanent settlers moved to the area, which would be called the village of Salter Path.”

One of Kay Stephens’ best sources is an unpublished memoir written by an island woman named Alice Guthrie Smith. Ms. Smith was born at the Rice Path in 1892, and she apparently wrote her recollections of her early life on the island sometime in the 1950s.

I have never seen her recollections, but fortunately Stephens quotes from them liberally.

Like quite a few other families, Alice Guthrie Smith’s family came to Bogue Banks from Shackleford Banks, the barrier island just to the east. Her grandparents, John Wallace and Hopey Ann Guthrie, left Shackleford Banks after he had a severe fall at the Cape Lookout Lighthouse and was left crippled.

Hopey Ann Guthrie apparently thought that life might be a little easier on Bogue Banks than at Shackleford. I am not sure why, though I suspect that she wanted a new home closer to the mainland and a bit more protected from the hurricanes that had been so hard on the villages at Shackleford.

John Wallace died two or three years after the family’s arrival at the Rice Path. Hopey Ann raised their large family on her own, living largely off the sea. The site of their home came to be known as Hopey Ann Hill.

In her memoir, Alice Guthrie Smith remembered when her family left the Rice Path and moved to Salter Path.

Kay Stephens quotes her in “Judgment Land”:

“Well, we lived to that house … until March 1896. (Our neighbors) Rumley Willis, Henry Willis, Alonza Guthrie and Damon Guthrie all decided they would move to the Salter Path. So, here we go. Well the day came for everybody to go down to the Salter Path and clear up their place, burn the pine straw and leaves and get their place ready to take their house down. So, Rumley put his house on a hill near the sound on the east side of the Salter Path that runs from the ocean to the sound. There were large oak trees all around his house. It was a beautiful place to build… There were only four families at first, but it wasn’t long before most of the people that lived to Rice Path, Yellow Hill, Bill’s Point and Belco moved to Salter Path and Broad Creek.”

The early settlers at Salter Path did not hold deeds to the property that they occupied, but saw the land being unused and made their homes there, a very old practice on the banks.

For that reason, the squatters, as they became known, later ran into legal entanglements, including a formal complaint from the land’s actual owner, a New Yorker named Alice Hoffman, who was Eleanor Roosevelt’s aunt. The legal issues were resolved in the 1920s and the Salter Pathers were allowed to stay on the land, though with restrictions that limited the village’s growth.

Community life at Salter Path revolved around a solitary church, a tiny graded school and, for the men at least, the general store. In her memoir, Alice Guthrie Smith recalled that first church in Salter Path:

“That was the place where all the churches in Carteret County would meet and have their summer picnics. Oh, wasn’t that a happy time for everybody present! Everybody was in love and harmony with each other, and we looked forward to that day. Everybody took their baskets full of good things to eat and after everybody got through eating and drinking lemonade…, we would have preaching and singing or somebody would make a speech. Now, that was the good old days!”

My mother was born and raised in Harlowe, a little community 12 miles from Salter Path on the mainland of Carteret County. I still remember her telling me about a Sunday school picnic on Bogue Banks. It may have been the only time that she visited the island as a child, which was around the time of these photographs.

She said it was quite an adventure. They made the journey by boat and at that age, she had rarely if ever traveled so far from home.

One of the state’s oldest and largest fisheries, the salt mullet fishery was a big part of life on Bogue Banks in the 1930s.

This is one of my favorite images from “Judgment Land”:

“In the summer when the mullet would run in big black schools out in the ocean, some of the settlers would come to the beach near Riley (Salter)’s home. They would encircle the mullet with the long nets which had … been knit by their women. Hundreds of pounds of mullet would be brought to shore. All day long the women would sit with their `sitting up babies’ between their legs and split and gut the fish. Their long cotton dresses and even their sunbonnets were slick where they had wiped their hands ….”

Mullet fishing is still important in Salter Path today, though perhaps it means more now to the fishermen’s hearts than it does to their pantries or pocketbooks. The beach seine fishery for mullet has come and gone elsewhere on the North Carolina coast, but a solitary crew of the village’s men still persist in fishing in much the same way as their ancestors did for many generations before them.

In “Judgment Land,” Kay Stephens also quotes Alice Guthrie Smith’s memoir about the way that the islanders traded their salt mullet for other things that they needed in life.

“They would wash and clean them so they could salt them down, head them up, and leave those barrels of fish on the beach until sometime later. In the fall, October or November, a large boat from Down East (the eastern part of Carteret County) would come up to Salter Path loaded with sweet potatoes and corn. They would trade the corn and potatoes for the fish that the people had salted.

“The way they got the fish from the beach to the sound was to tie a rope around the barrel and two men would get a long pole and put it through the rope, take the poles on their shoulders, and carry the barrels down the Salter Path to the sound. There they put them in skiffs, took them out to the deep water where the large boat was and put them aboard the boat after they took the corn and potatoes out.”

According to legend, the coming and going of those mullet fishermen wore a sandy path from the ocean beach across the dunes and swales to the shores of Bogue Sound. The path ran by the home of Riley Salter and his family, which led people to call it Salter Path and gave the village its name.

When Kay Stephens was researching “Judgment Land,” she spent a great deal of time with Lillian Golden, a local woman who was born on the island in 1901.

I love Lillian Golden’s descriptions of island life because they are so granular: in Ms. Golden’s words, you can really hear and understand the practicalities of how the Bogue Bankers fashioned a life there on the edge of the sea.

In this excerpt from “Judgment Land,” Stephens recounts how Lillian Golden described how the islanders made their mattresses.

“The villagers made their ticking out of flat homespun. The mattress that was placed on top of the slats was stuffed with seaweed. A feather mattress was placed on top of the seaweed mattress. The seaweed used in the mattresses was gathered along the shore and spread on bushes. It was left there through several rains so the salt water and other material could wash out. The sun would then bleach the seaweeds.”

Well into the 20th century, the villagers made feather mattresses. Stephens talked with another local woman, for instance, whose mother had a mattress stuffed with robin feathers.

In the 1800s and into the 1900s, the islanders often caught robins and other songbirds in fishing nets spread among the wax myrtle and yaupon bushes around their homes. They valued the birds for their feathers, but also sought them out in order to feed their families.

Now and then, the sea provided very different kinds of gifts. In her memoir, Alice Guthrie Smith recalled, for instance, how wind and waves knocked a load of lumber off a schooner during the great hurricane of 1885.

The lumber washed up on Bogue Banks and after the storm, she wrote, “everybody that needed lumber went over to the beach and pulled up all they wanted. Dad saved enough to start him a small house to the Rice Path.”

I am always surprised, when I visit the old homes on Salter Path or on Ocracoke or some other island village, how often people tell me that this room’s floor or this chest of drawers or this table came off a shipwreck years ago.

It always feels as if there is no limit to the way that the islanders were bound to and shaped by the ways of the sea.

Now and then, I get a glimpse in “Judgment Land” at something that I rarely hear talked about: the fear that the island’s women felt for their safety and the safety of their daughters when their husbands were away fishing and hunting or when their husbands had died and left them on their own.

Kay Stephens tells the story, for instance, of a night during the Civil War when three men from the mainland forced their way into the home of Francis and Horatio Frost and raped two of their daughters. At the time, Horatio and their only son were gigging flounder on Bogue Sound.

In another part of the book, Lillian Golden recalled the fear that she and her widowed mother felt at their home in Salter Path when she was a girl.

“The neighborhood wasn’t thickly settled, and you didn’t think of calling nobody … I was scared to go to sleep nights. We were in the woods. The other young’uns had a father with them, you see.

Like so many other young women of the time, Lillian did not wear make-up and rarely wore jewelry in the hope that she could avoid men’s attentions.

I found Lillian Golden’s recollections of her widowed mother especially entrancing when I reread “Judgment Land” the other day.

Her mother, Mary Francis Smith, took her husband’s death very hard. He was scarcely 30 years old when he died after a long illness in 1901. Beset by grief, Laura Francis was visited by nightmares for years.

Lillian told Kay Stephens that, in order to comfort her mother, she slept with her, nuzzled against her back, from the time that she was a little girl until she was married in 1918.

Yet for all that, Mary Francis managed to provide for herself and her children.

”She clammed and caught soft-shell crabs in the spring and summer. She took in sewing, sometimes staying up late into the night to finish a dress that was wanted the next day. In the fall and winter she and her children would cut wood and sell it by the cord …

“She would cut the leaves off the yaupon (bushes) and sell them to a factory on Harkers Island. (Harkers Island is 18 miles east of Salter Path.) There the leaves were cured and put into sacks and sold under the brand name `Carolina Tea.’

“In 1905 after her aunt Mahalia Ann Guthrie was no longer able to serve as the village midwife, Laura Francis began her long career delivering the babies not only in Salter Path but elsewhere on the banks.”

She was a little bit of everything: fisherwoman, seamstress, woodcutter, herbalist, midwife and mother, as well as, for a time, the village’s postmistress.

To get by, Mary Francis saved and reused every little thing, kept two big gardens and spun her own thread and made her family’s clothes. Her neighbors shared and together they made do and got by.

My friend Karen Willis Amspacher is the director and guiding spirit at the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island. Many of her ancestors came from Shackleford Banks, the island I mentioned earlier that is just to the east of Bogue Banks.

More than once, when we have been discussing how hard it was to survive on those islands back in the day, Karen has just shaken her head and told me, “Those were some tough folks, David. That’s all I can say. Those were some tough folks.”

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.