Janet Gillikin, 82, can’t help but tell the story again, laughing the whole way through. “I’ll never forget it my whole life.”

She and Sonny Boy Stacy were children playing on a fish-house dock on their native Harkers Island when Gillikin suggested they race to shore. Running hard as he could, “Sonny Boy started swerving to the side,” Gillikin said. “And he fell right into the water.”

Supporter Spotlight

Judging by Stacy’s wailing, Gillikin was sure the boy had slammed into bags of hard clams fishermen stored under water, but when Gillikin asked if he was hurt, Stacy said no.

“Then why are you screaming?’” Gillikin asked, to which Stacy cried, “Because I got my chewing gum wet.”

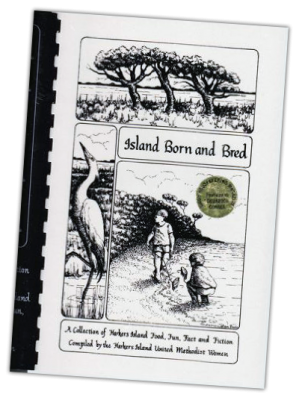

With its glimpse of island life, Gillikin’s tale is more than a humorous anecdote, just like “Island Born and Bred,” the cookbook that records the story, is more than a recipe collection. Back on store shelves after a two-year hiatus, “Island Born and Bred” is not just Harkers Island’s community cookbook. It’s a definitive history told by the people.

“You can hear their voices in a very intimate, community kind of way,” said historian David Cecelski, who uses “Island Born and Bred” to teach history classes at Duke University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

“If I had to pick 10 books on the folklife on the North Carolina coast for any time period ever, that cookbook would be on it.”

Supporter Spotlight

Recipes were an excuse

“Island Born and Bred” was never intended to be a scholarly text. “It is our attempt to tell the people who come and look that there is more to this Island than a weekend retreat or a Sunday afternoon drive. This is our home,” the book’s editor Karen Amspacher read from the hand-typed, black-and-white pages.

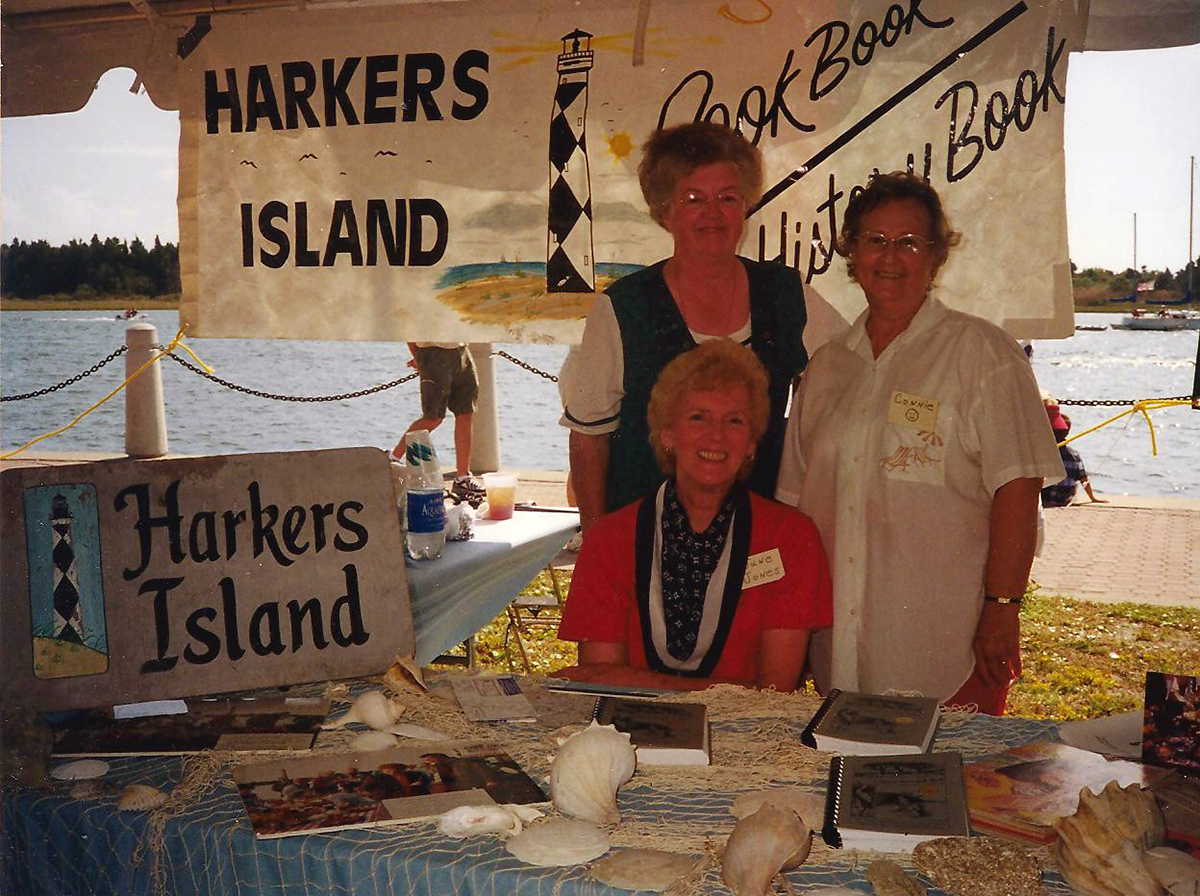

In 1987, Amspacher suggested the Harkers Island United Methodist Women craft a cookbook to fund its ministry’s good deeds. Not long from college work as an oral history transcriber, the Harkers Island native was certain that if somebody didn’t record stories she and others had heard their whole lives, those firsthand accounts would be lost forever. Amspacher envisioned recipes as merely the hook drawing readers into narratives. Some of her fellow Methodist Women weren’t so sure.

“I thought it was outrageous,” said Gillikin, who was Harkers Island United Methodist Women president at the time. She believed, “There are too many cookbooks out there. Everybody has 10 or 12 cookbooks. What do we need with another cookbook?”

The ladies eventually came around, and “Island Born and Bred” ended up a cookbook people did need. People everywhere. Plans in 1987 to print just 500 copies of a 200-page book turned into the sale of 10,000 copies of a nearly 400-pager by the end of 1988 and thousands more shipped far and wide over the next 33 years.

From the beginning

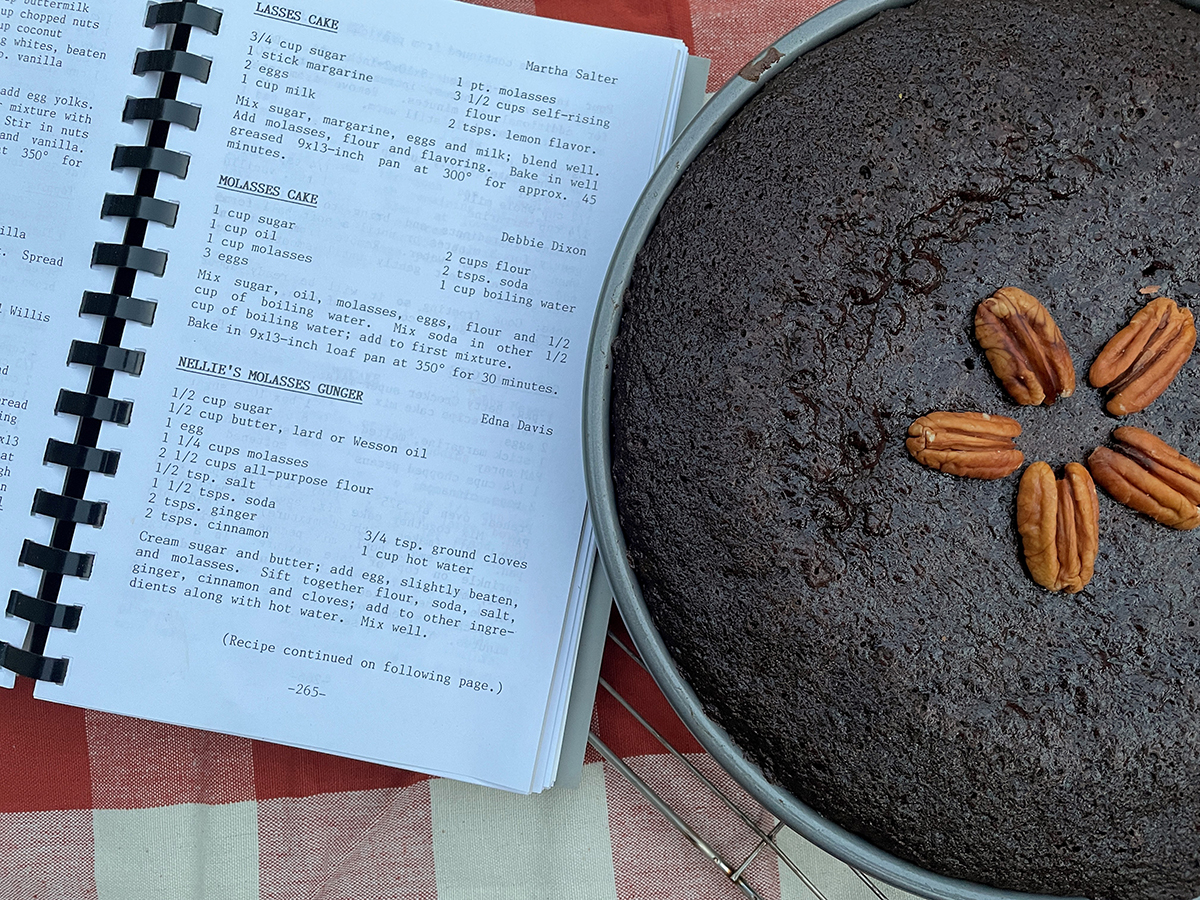

Harkers Island residents put their hearts into the endeavor, sharing 625 recipes from old-timey classics like Fried Clams with Gravy to contemporary Microwave Swiss Steak. Stories, facts, poems and folklore came handwritten on napkins, slips of paper and legal pads or told to the United Methodist Women, who tape recorded and transcribed exactly what they heard.

An entire dictionary devoted to “Island Talk” listed terms like “I shan’t” (I shall not) and “slick cam” (slick calm) written phonetically, giving voice to the distinctive Harkers Island brogue.

Time and again, contributors honored determined ancestors who relied on their wits to thrive on nearby ribbons of sand — Shackleford Banks, Core Banks, Diamond City, Cape Lookout — places that afforded inhabitants freedom, togetherness, a bounty of seafood and stunning landscapes akin to heaven on earth.

The book’s simple sketches, done by local artists, depict long-gone island scenes like boatbuilders at work, nets hung near once-numerous fish houses and a bonnet-crowned grandmother sitting on the “pizer,” an island word for “porch.”

Illustrations based on actual photographs included a poignant moving-day scene. The original circa 1911 photograph measured only about an inch square but still captured Clem and Louise Hancock on Shackleford Banks driving a horse-drawn wagon full of their belongings to more stable ground. Relocating became common. The “Island Beginnings” chapter traces Harkers Islanders’ lineage from pre-1650 settlements on outlying barrier islands to late-1800s hurricanes that forced residents to begrudgingly float their homes on boats across the sounds to fresh starts on Harkers Island.

Day after day, the United Methodist Women gathered stories and recipes. Every written word was hand-typed by volunteer Ruth Paylor on an IBM Selectric typewriter. Each page had to be perfect, no Wite-Out allowed because it would show up as a blob on the stat camera that print shop workers used to transfer Paylor’s typing to printing plates.

Pages arrived at the church fellowship hall in random lots, pages 53-86 one day, 95-175 another. “We had a room full of fish boxes stacked with batches,” Amspacher said. For weeks, the women collated pages by spreading them out in numerical order on a maze of tables across the fellowship hall. Volunteers wound the labyrinth, picking up page after page until a full book was assembled at the end.

“And they started reading the pages,” Amspacher said.

As the women navigated, they saw friends’ recipes, familiar tales and names of places long gone.

The maze ended at a hand-operated, book-binding machine the women borrowed from the print shop. Stacks of pages had to be carefully placed so that the 15 perforations on each sheet aligned perfectly with the plastic ring binder.

“We put together the first book, and we cried,” Amspacher said, fighting back tears. “We cried because we knew in our hearts, even though we didn’t want to admit it to each other, that Harkers Island was gone.”

A promise to never forget

Harkers Island quickly changed from a remote coastal fishing village in the early and mid-1900s to a tourist haven by the time the book project started. “I think my generation was the last to know it as it was,” Amspacher said.

“Island Born and Bred” held local culture for the ages.

In 1989, the book won the North Carolina Society of Historians’ Award of Merit “for its contribution to the preservation of North Carolina history.” It spawned more Harkers Island historic journals written by residents and helped inspire Harkers Island’s popular Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center. ABC’s “Good Morning America,” Good Housekeeping magazine, local television shows, numerous newspaper articles and glowing reviews all featured the work.

The United Methodist Women shipped orders to England, Canada, Australia, the Caribbean and every state in the U.S.

“I got a call from somebody in Billings, Montana, one night,” Amspacher recalled. “She said she had never seen the ocean but that she really appreciated the community because it reminded her of home.”

Even Harkers Islanders were moved, way more than they expected. After the book’s release, initially skeptical residents realized “Island Born and Bred” was special.

“I’ll be looking at it and I’ll stumble on a story and get to reading it and forget all about the recipe,” said Dean Johnson, whose grandmother Nannie Raye Poole’s recipes appear throughout the book.

Johnson regularly taps her stained and tattered copy. Most recently, he prepared Poole’s time-consuming Conch Stew, page 194, for a neighbor wishing she could taste it again.

The rubbery shellfish must be pounded for at least an hour to tenderize the meat. As he talked, Johnson craved his late grandmother’s Fried Clam Fritters, page 190, that required fresh clams be gutted and then washed three times to remove grit. He launched into a story about Poole spending all day Saturday preparing Stewed Hard Crabs, pages 198 and 199.

“She started by catching and cleaning the crabs,” Johnson said, and ended by adding the island’s signature cornmeal dumplings.

Reading and rereading has convinced Johnson to gather loved ones more regularly, as Poole always did, to share local favorites, including the true Harkers Island Oyster Roast, page 206, he planned for the weekend. Like his ancestors, Johnson would cook wild oysters over a wood fire and serve them with Fried Cornbread, page 78, sour pickles and cold Pepsi.

“The heritage of it just makes me feel proud to be from where I am,” Johnson said, “and of those people who paved the way.”

Over the years, “Island Born and Bred” did more than inspire. Proceeds helped many people in need, including North Carolina families economically devastated by a 1987 toxic red tide that closed commercial fishing; South Carolina victims of 1989’s Hurricane Hugo; and a Morehead City family who suffered a kitchen fire days before Christmas.

Profits continue to sustain Harkers Island United Methodist Church and its ministry work, the Rev. Lee Pittard said. Church leaders plan another printing soon. Amspacher expected the several hundred books released this fall to sell out before Christmas.

“But how many have been sold and how much money has been made is immaterial,” Amspacher said. “I can go through the book and tell you every one of the people, what their story is, who they were, what they’d been though.”

“This cookbook was Harkers Island promise to never forget.”

Wanda Willis’ Hurricane Cake

Wanda Willis’ “‘Hurricane Cake Recipe’ was recognized by Good Housekeeping magazine in 1989 and helped make the ‘Harkers Island cookbook a best-seller nationwide, and her ‘stew-beef-and-rutabagas’ helped build the Core Sound Museum,” according to her obituary. “Her kitchen table welcomed many traveling preachers, MYF groups, ballplayers, family members, and friends from far and wide to enjoy her cooking and hospitality.” Willis was “Island Born and Bred” cookbook editor Karen Amspacher’s mother.

Hurricane Oatmeal Cake

1 cup oatmeal

1¼ cups boiling water

2 eggs

1 cup brown sugar

1 cup granulated sugar

1/2 cup vegetable oil

1½ cups flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

Combine oatmeal and boiling water; set aside. Beat together eggs, sugars and oil until blended. Add sifted flour, baking soda, salt and cinnamon. Add oatmeal mixture.

Pour into a greased 9-by-13-inch baking pan. Bake at 350 degrees for 30-35 minutes.

Topping:

1 cup coconut

1 cup brown sugar

6 tablespoons melted margarine (see cook’s note)

1/2 cup chopped pecans

1/4 cup evaporated milk

Cook’s note: Butter works just as well in this recipe.

Mix together topping ingredients until moist. Spread over cake. Broil until topping is light brown and crunchy, about 2 minutes.