Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

The Albemarle region is home to Colonial North Carolina’s original four counties. Of these four, two contain prominent historic towns, Pasquotank and Chowan, and one, Currituck, is now an Outer Banks destination. In some ways, Perquimans may be the odd county out.

Supporter Spotlight

It was not the home of a center for higher learning like Elizabeth City or Blackbeard’s friend in government. But its small size did not prevent Perquimans County from having an exceptional impact on the history of North Carolina’s religion, sports or culture.

Perquimans County was one of the original precincts of Albemarle County, the first county established by the Lords Proprietor of North Carolina in 1663. In his history of North Carolina counties, David Leroy Corbitt traced the precinct’s origins as early as 1668 and noted the county’s boundaries: the Little River to the east, Yeopim River to the west, and the Virginia border. The northern section was later taken to form Camden and Gates counties.

The Perquimans River bisects the county.

Perquimans County was settled in the 1660s by men and women from Virginia migrating south, including early Colonial leader George Durant. They were at first sold land by the Yeopim Native Americans who lived in the area. After this earliest English settlement, the county received one of its first notable visitors in 1672, one who would influence the development of the county for centuries.

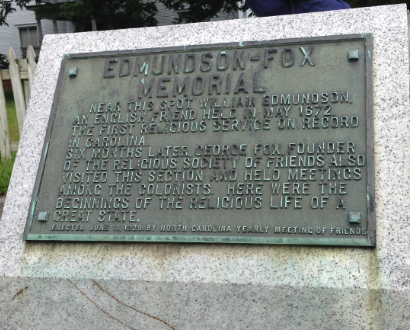

George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, introduced the major tenets of the religion in England in the 1640s. He then felt called to visit adherents to his religion living in the Americas. From Virginia, he arrived in North Carolina in 1672 and wrote in his journal that the journey involved no established roads and was “full of cruel bogs and swamps; so that we were commonly wet to the knees, and lay abroad at nights in the woods by a fire.”

Supporter Spotlight

During this visit, supported by his follower William Edmundson, Fox converted a number of Perquimans County residents.

Quakerism’s tenets greatly affected the development of Perquimans County. Quakers believed in purchasing land from Native Americans, as opposed to taking it by force, meaning that they did not immediately acquire the most fertile lands. Such lands were the best for tobacco production, so the Quakers focused on wheat and corn in the early years of the county. The Quakers, guided by their views on the equality of all people, also started to fight against slavery in the late 1700s. Many Perquimans County residents advocated against slavery and freed their slaves in a process known as manumission. According to historian Stephen B. Weeks, one of the most notable Quaker opponents of slavery in the county was Barnaby Nixon, who became known for both his views on slavery and his vegetarianism.

The Quakers were eventually displaced by pro-slavery settlers who hungered for the fertile land of the Albemarle Region. By 1860, Edwin Hergesheimer’s map showed that 52.1% of Perquimans County residents were enslaved, the second highest total in the Albemarle region.

Fifty years after the first Colonial settlement, descendants of the first settlers built one of the most famous Colonial houses in the state. The Newbold-White House is usually accepted as North Carolina’s oldest brick house. It was built around 1730 on land at one time associated with the famous Blount family, although historian Tom Parramore believed it may have been built even earlier.

The house changed hands multiple times until it was purchased by the Perquimans County Restoration Association in 1973, when the county began to return it to its former appearance. The Newbold-White House can be visited and toured today. It is an exceptional, publicly accessible relic from the earliest period of the Colony.

The county’s small population meant it developed differently from its neighbor to the east, Chowan County. While Edenton was settled quickly and became a prosperous town, Perquimans County did not have an incorporated town for decades. The county court met at private homes for several decades. Perquimans County’s first recognized town, Hertford, was settled in 1701, according to the “North Carolina Gazetteer,” but not incorporated until 1758.

Hertford became known for its stately homes and for its swing-span “S bridge.” Until its disassembly earlier this year, it was one of the few remaining S-shaped bridges in the country. The Perquimans County Courthouse, built in 1824, is one of the oldest extant structures in the county and is a fine example of Federal-style architecture.

Perquimans County remained small throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Its population decreased from 9,466 to 9,178 between 1880 and 1960. But there were still a number of notable people who called the tiny county home. Arguably the most famous was Jim “Catfish” Hunter, a Major League Baseball pitcher with the Oakland Athletics and New York Yankees. Hunter won more than 200 games in his illness-shortened career, pitched a perfect game, and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987.

Catfish became known for his laid-back attitude and country witticisms. Once, in reference to his teammate Reggie Jackson, he famously said, “The difference between God and Reggie Jackson is that God doesn’t think he’s Reggie Jackson.”

A close competitor in fame was Wolfman Jack, the famous midcentury radio DJ and a resident of Perquimans County later in his life. Born Robert Weston Smith in Brooklyn in 1938, the Wolfman was known for his distinctive gravelly voice. He was a mainstay of early rock-and-roll radio from his perch at several American-Mexican border stations in the 1960s. His 1995 New York Times obituary noted that his famous voice had given him “something of a cult following as one of America’s best-known radio personalities.”

Wolfman Jack’s fame led to several commemorative songs and a spot in George Lucas’s 1973 film “American Graffiti.” Although he lived in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, when he died in 1995, Wolfman Jack was buried in Belvidere, where he had moved nine years earlier to live with his wife’s family.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have brought a number of opportunities to Perquimans County. Albemarle Plantation is a planned community on the Albemarle Sound that opened in 1990. As noted in the Perquimans Weekly, Albemarle Plantation is home to 475 families and provides a golf course as well as a marina for residents.

There is also a military facility, the Harvey Point Defense Testing Activity, located on Harvey’s Point between the Albemarle Sound and the Perquimans River. The county continues to be mostly rural, although it is an attractive bedroom community for commuters from Elizabeth City.

While most of the Quakers left in the 19th century because of their opposition to slavery, there are still two Quaker meetings left in the county. The Quaker heritage remains and serves as one of the many factors that make Perquimans County a unique part of North Carolina’s original Albemarle region.