Editor’s note: Bland Simpson is a friend of the North Carolina coast and of the entire Tar Heel State. He’s a friend and supporter of Coastal Review and an occasional contributor. Likewise, he’s a friend of our publisher, the North Carolina Coastal Federation, having served long and faithfully on its board of directors.

He’s the Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, where he has taught since 1982.

Supporter Spotlight

He’s an accomplished musician, having been the award-winning Red Clay Ramblers’ piano player since 1986. His music career dates back to an earlier time, the heyday of the singer-songwriter.

Bland recently marked the 50th anniversary of his early ’70s quartet’s Columbia Records album, “Simpson” with a remastered release available at blandsimpson.bandcamp.com. All proceeds from the album’s sales go to the Food Bank of Central & Eastern North Carolina.

He has collaborated on numerous musicals, including “King Mackerel & The Blues Are Running” and “Kudzu,” and he has written numerous books about North Carolina.

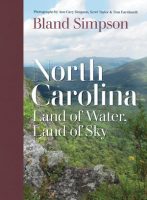

His latest work, “North Carolina: Land of Water, Land of Sky,” with photography by additional friends of ours, his wife and collaborator Ann Cary Simpson, Scott Taylor and current federation board member Tom Earnhardt, is set for release Tuesday by UNC Press.

An in-person and online streaming book launch event is set for 5:30 p.m. Tuesday at Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill. Flyleaf Books is offering seating for up to 25 in-person guests, with priority access given to those who purchase the book. If you preorder a copy through Flyleaf, you are asked to use the order comments form to indicate whether you would like one or two seats held for you at the in-person event. To purchase a copy of the book and/or register for the in-person event, visit https://www.flyleafbooks.com/event/simpson-2021.

Supporter Spotlight

The following is adapted from “North Carolina: Land of Water, Land of Sky,” by Bland Simpson, with photography by Ann Cary Simpson, Scott Taylor and Tom Earnhardt. Copyright © 2021 by Bland Simpson. Used by permission of the publisher, www.uncpress.org.

Pecans

Not far from the river, just south of Elizabeth City, a large grove of pecan trees once grew, and cattle grazed lazily there. I never ventured into it, only rode past it on my bicycle, stopping whenever I was out that way (some miles from our home near Horner’s Sawmill) just to regard the blithe, benign way the modestly-spaced pecan tree leaves distributed light to the forested pasture below, the cattle chewing at leisure in their dappled light.

No other large trees growing so closely together, except beech perhaps, let so much light through their branches and crowns and still maintained shade: a bright shade, if you will. Just east of town, across the Camden causeway on the old Sawyer plantation, stood another such grove, which we passed often, on our way to see our Ferebee cousins in Camden and on our way to the Outer Banks.

At the age of eight, I had not yet fully formed my thoughts about the nature of pecan trees and the properties of sunlight shining upon and through them. That would come much later, when I started rambling around eastern Carolina in my twenties and noticing how many farmsteads, large and small, had pecan groves off to the side – two acres, maybe, or twenty – of the main house, or had the main house standing within them. Sometimes only the old groves still stood, the homestead itself long gone.

Here in Beaufort, at our family’s house on Orange Street in sight of Taylor’s Creek and only a couple miles from the widening inlet to the sea, five pecan trees held down the fort – two small ones out by the street, three large ones in the back yard. Summer evenings we sat under them and listened as ocean breezes and winds blew through them, sometimes mildly, sometimes vigorously with the full authority of Neptune’s Atlantic. They made a fresh, brushing sound that rose and fell, and the little postage-stamp of a yard seemed enclosed by the sound as much as by the body and branches of the big pecan trees themselves, and I loved the way the southerly breezes of summer soughed through their feathery leaves at night with the softest shushing, insistent, though, like all the sighs of the world.

There was a long view out from under one of them, and through it one’s eye was drawn to a pair of massive pecan trees, lovely twin sisters seventy-five yards to our north, whose crowns danced and swayed in the summertime almost with abandon, showing me in their dancing the inlet winds, the winds that have come here unabridged and uninterrupted and unimpeded all the way from the wide Sargasso Sea. How often and how long I stared and wondered: a cleft in the high, billowing crown of one of those two pecan trees might just be a portal to another world.

So it was that (till one fateful night here in Beaufort, when Hurricane Florence felled one of the sisters) the two dancing pecan trees who were there for so many years swayed, presenting hypnotic delight and delight only, and the hands of the Great Choreographer who directed it all were at play, at play, at play.

The Battle of Rich Inlet

Several of us met about six years ago at the NC Coastal Federation’s Fred and Alice Stanback Environmental Education Center, our regional headquarters in Wrightsville Beach, and went on down with the Federation’s skiff and put in at the Lee’s Cut landing. Just after nine on a hot, blue-sky late August morning, we motored on up the Waterway, the Federation’s genial and skillful advocate Mike Giles at the helm, to the southern channel that would lead us over to Figure Eight Island’s soundside and then on to Rich Inlet itself.

First we would pick up Derb Carter, rock-steady leader of the Southern Environmental Law Center with his powerful ringing baritone and North Carolina Audubon’s coastal waterbirds champion Walker Golder at Figure Eight and continue past the huge, growing, hundred-acre tidal flat to a spot where we could film and tell a tale: why this natural inlet did not need that billion-dollar community’s board-of- directors-proposed 16,000-ton rock-and-sheet pile wall (a terminal groin, in engineering and political parlance) cutting through it.

And putting an end to the tidal flat and the living breathing inlet as we knew it.

We beached on the upper back side of Figure Eight Island long enough to collect Derb and Walker and to wish a top-of-the-morning to one of our state’s most noted conservationists, Fred Stanback of Salisbury. Fred, lean and wry, stood at ease in the morning sun right at the shallows.

“Sure you don’t want to come on with us, Fred?” asked Tom Earnhardt of Exploring North Carolina, who was directing and producing this project. Fred smiled and shook his head.

“You all have a good day out there,” he said, standing still and unwavering, an elder statesman by the water’s edge as we pushed off, waving and calling to us when we were twenty yards out:

“Good luck!”

This honorable man and his wife Alice split their time between the island and their home in Salisbury. They had staked much of their family’s resources on preserving and protecting North Carolina’s natural world, and no one close to the task believed our state’s environmental movement would have been so strong, or accomplished so much, without them.

Soon, under Mike Giles’ sure piloting, we were on the far side of Rich Inlet, looking back at the enclave that seemed small and unthreatening at a distance, the sun climbing now and the wind picking up, and Walker pointed to the tawny sea oats waving in the breeze and recalled:

“I was out here recently, last October, very early in the morning with my son. And the shaft of every one of these sea oats was covered with monarchs that had spent the night on them, as they were migrating. When the sun came up and as the day warmed, the monarchs climbed slowly up the sea oats, till the top one on each shaft reached the tip, and then it’d take off, singly, and fly away, and that just kept on, till at last they were all away.”

We would stay out on the lower, southwest end of Lea-Hutaff Island (which NC Audubon would later preserve in the summer of 2019) for over half the day, finding different spots to shoot, moving around and up the back side of the island, staying out of the wind, walking in the creeks. Minnows swam around my feet, gulls swept in to caw and check us out, white egrets glided by without comment.

Our argument was compelling: Rich Inlet had a two-hundred-year history of migrating back and forth within a half-mile range, now close-in to Figure Eight, now close to Lea-Hutaff; a groin channel would finish off the inlet’s tidal flat forever and its abundant wildlife would disappear; all the island’s homeowners would have to finance privately the multi-million-dollar jetty, not just those whose homes were proximate to it; and, should it later be judged environmentally deleterious, a high likelihood we thought, all the homeowners would also be on the hook for the groin’s future multi-million-dollar removal.

Once we wrapped, several of us boated back down to the Dockside on the Waterway near the Wrightsville Beach bridge. After more than half a day walking around in the shallows out in the great wide open, telling the story of just what was in the balance here, barefoot and pants-legs rolled, sitting down for a few minutes in the shade felt right good to me, face to face with a tall glass of sweet tea and an agreeably large crabcake sandwich.

That moment would live in my memory as one of the truly grand days I have ever been given, the broad green plain of marsh and all those interwoven creeks we worked in, the purpose that had brought us there, the pitched battle to preserve North Carolina’s last natural inlet that was moving and flowing just as God had flung it there, and then, too, just being out there together with these wonderful cohorts, bonded by it all. I simply sailed up through the flat eastern terraces and back to the hill country of western Orange County that evening, replaying the moments and thinking a good long while about what it might mean, what it could mean to so many – men, women and children who loved this inlet, boated to it often and who were joined in this effort; fish, turtles, birds, and butterflies in migration, stopping off by the thousands in that small patch of Rich Inlet sea oats for one good night’s rest – for all those devoted to keeping this piece of the Lord’s handiwork intact, simply to have done the right thing for the right reason.

When word came forth a year and a quarter later that the Figure Eight homeowners had taken stock of this potentially-ruinous plan and at long last flat voted it down, people all over the state who love our wild Carolina coast stopped and smiled, remembering their best and oldest hopes.