The great battles of the Civil War have been etched into American history — Bull Run, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, the sieges of Atlanta and Petersburg.

While these are seen as defining moments in the war, there were other significant campaigns and skirmishes not as well known. One, Gen. Edward Wild’s raid of Elizabeth City in December 1863 when about 2,000 Black soldiers set free hundreds of enslaved North Carolinians, is getting new recognition.

Supporter Spotlight

A physician and ardent abolitionist, Wild had assembled and commanded a brigade of the United States Colored Troops. Many in the USCT had lived in North Carolina.

“It was the first time soldiers of color operated in North Carolina … in combat operations,” said Marvin Tupper Jones, executive director of the nonprofit history preservation organization Chowan Discovery.

A new North Carolina highway historical marker commemorating Wild’s Raid is set to be unveiled at 2 p.m. Saturday at Elizabeth City’s Mariner’s Wharf Park on Water Street.

An early test

The USCT had been in combat earlier in 1863, but those battles had been in South Carolina and other Southern states. Wild’s Raid would be a first test for many of the troops he had recruited and trained in North Carolina.

In February of 1862 Union forces took control of Elizabeth City, giving them command of the bays and sounds of northeastern North Carolina. By the fall of 1863 Union forces controlled most of what is now the Hampton Roads area of Virginia.

Supporter Spotlight

“At the operational level, Suffolk itself was a decisive point” for the Union, Lt. Col. John Yingling noted in “The Suffolk Campaign: An Analysis off a Civil War Campaign.” “… it represented part of the key defenses of Norfolk.”

But the area between the Virginia-North Carolina state line and Elizabeth City was an untamed no-man’s land, rife with guerrilla activity and Southern sympathizers.

On the eastern side of the contested land, the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal had just been completed in 1859, offering a water route to move supplies and men.

On the western side lay the Dismal Swamp Canal, a direct route to the headwaters of the Pasquotank River and Elizabeth City.

Completed in 1805, the Dismal Swamp Canal links Deep Creek, Virginia — a former unincorporated community that’s now part of Chesapeake — and South Mills, North Carolina. It’s one of two inland water routes that connect Chesapeake Bay and the Albemarle Sound.

Confederate activity along both waterways made communication uncertain and difficult.

Even though USCT units had proven themselves in battle, they were primarily seen as support units, with many commanding officers believing them incapable of maintaining the discipline needed for combat.

Wild was determined to disprove that belief. His soldiers had trained extensively when he recruited them earlier in the year, and he now had almost 2,000 men under his command.

Wild’s Raid began Dec. 5, 1863. His strategy called for a two-pronged attack into rebel territory.

Wild would lead 1,100 men from Suffolk, Virginia, following a land route parallel to the Great Dismal Swamp Canal. Another column with 630 men left Kempsville, Virginia, in what is now Virginia Beach, marching south through Currituck County, according to documents that Marvin Jones provided to the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

Union Gen. Benjamin Butler, who took command of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina on Nov. 13, 1863, had recently returned from New Orleans to the site of his first wartime command.

Wild, in his “succinct account of my late raid, with observations hereon,” submitted to Butler at the end of December 1863, described a military snafu.

“Two small land steamers were loaded with rations to accompany us along the canal, but by some unaccountable blunder they were sent astray through the wrong canal,” he wrote. The two steamers did eventually rendezvous with Wild at Elizabeth City.

They were in rebel territory, but Wild didn’t hesitate.

“We were thus obliged to live on the country for a few days; which we did judiciously, discriminating in favor of the worst rebels,” he wrote.

His Currituck column rejoining him at South Mills, Wild proceeded to Elizabeth City, building “a substantial bridge over the Pasquotank below South Mills, constructed by Col. Holman and Major Wright of material taken from the house and barn of a rebel Captain nearby,” Wild wrote.

The war had devastated Elizabeth City. Embedded with Wild’s troops, a New York Times reporter identified as Tewksbury wrote “Invasion of North Carolina by General Wild’s Battalions,” giving a detailed account of the raid.

Describing Elizabeth City in December 1863 Tewksbury reported, “Three years ago it was a busy and beautiful little city, noted for the number of its stores and manufactories, the extent and variety of its trade, for its enterprise and the rapid increase of its population. Now most of the dwellings were deserted, the stores all closed, the streets overgrown with grass, its elegant edifices reduced to heaps of ruins by vandal Georgian troops, the doors of the bank standing wide open, and a sepulchral silence brooded over the place.”

For Wild, Elizabeth City was a base of operations, but he had no plans for an extended stay, remaining there only for a week.

“While there, I sent out expeditions in all directions, some for recruits and contraband families, some for guerrilla, some for forage, some for firewood, which was scarce and much needed by us,” Wild wrote.

The land surrounding the city was a hotbed of rebel resistance.

“The guerrillas pestered us,” Wild reported. “They crept upon our pickets at night, waylaid our expeditions and our Calvary scouts, firing upon us whenever they could; but in marching, our flankers beating up the woods, generally drove them. We ambuscaded them twice without success. Pursuit was useless.”

Yet pursuit was not always useless.

“Col. Holman burned two of their camps between Elizabeth and Hertford, taking some of their property such as guns and horses,” Wild wrote.

A prisoner was also taken.

“Daniel Bright of Pasquotank County, whom I afterwards hanged, duly placarded thus: ‘This guerrilla hanged by order of Brig. Gen. Wild,’” he wrote. “All of our prisoners had the benefit of a drum head court martial,” or trial during action.

Despite his successes, Wild was a controversial figure who took a harsh view of the rebellion and responded severely when he encountered resistance, according to his writings.

“Finding ordinary measures of little avail, I adopted a more rigorous style of warfare —burned their houses and barns, eat up their livestock, and took hostages from their families,” he wrote.

Leaving Elizabeth City Dec. 18, 1863, Wild again split his command, this time sending Col. Alonzo Draper to Shiloh, a hamlet in Camden County that was little more than a crossroads.

Draper had the most intense action of Wild’s raid. “He had had three encounters with guerrillas,” Wild wrote.

The most significant of those three was at Sandy Hook, between Shiloh and Indiantown in Camden County where, Draper reported, “… our advance guard encountered the enemy’s scouts. On our right, at a distance of five or six hundred yards, was a wooded swamp, impenetrable for our skirmishers; we were therefore under the necessity of advancing under great disadvantage, or of retracing our steps. We chose to advance and were directly attacked by a force in ambush behind a thicket in the edge of the swamp … This force numbered probably one hundred and fifty, possibly two hundred …”

Undaunted, Draper laid out his plans that included flanking the Confederate forces and a bayonet charge. His report includes the confusion of the fog of battle. Capt. Robert Smith with 2nd North Carolina Regiment was supposed to advance to the edge of the woods by the swamp and then make a bayonet charge. But “… misapprehending his orders, he sheltered his men and recommenced firing,” Draper wrote.

Draper ordered his men to charge with fixed bayonets, which they did, while running directly into enemy fire.

“As they were passing … over the open ground the enemy continued firing upon them; but the moment the assaulting party gained the edge of the swamp, they precipitately abandoned their position and could be distinctly seen rushing out of the thicket. Before we could overtake them, they had escaped into the swamp, by a path familiar to them, but at that time impassable to us,” Draper recorded.

Wild’s account also noted the bloodshed at Sandy Hook, with 13 armed guerillas killed or wounded. His own men fared only slightly better with 11 lost.

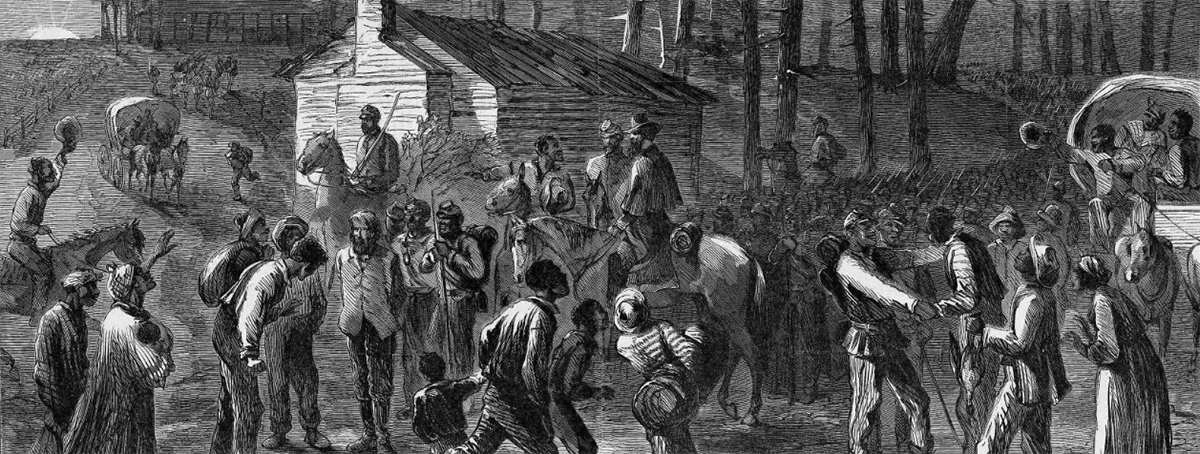

Still, Wild’s Raid was a deemed success. By Wild’s estimation, some 2,500 enslaved people were freed, but he was disappointed that only between 40 and 100 were “able bodied” for military duty.

But as Butler wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the military significance was notable.

“I think we are much indebted to General Wild and his (N)egro troops for what they have done and it is but fair to record that … all committees agree that the (N)egro soldiers made no unauthorized interferences with property or persons, and conducted themselves with propriety.”

Tewksbury, though, writing for the New York Times, seemed to grasp that the raid was more than a military success.

“It is the first of any magnitude undertaken by (N)egro troops since their enlistment was authorized by Congress, and by it the question of their efficiency in any branch of the service has been practically set at rest,” he noted.

Then, noting the irony of formerly enslaved men traipsing through forest and swamp searching for guerrilla forces, he ended his article writing, “It is an instructive turn of the tables that the men who have been accustomed to hunt runaway slaves hiding in the swamps of the South, should now, hiding there themselves, be hunted by them.”